In ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy is unequivocal, but the optimal time to administer the loading dose (LD) of a P2Y12 inhibitor is the subject of debate and disagreement. The main aim of this study was characterize current practice in Portugal and to assess the prognostic impact of P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration strategy, before versus during or after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

MethodsThis multicenter retrospective study based on the Portuguese National Registry on Acute Coronary Syndromes included patients with STEMI and PCI performed between October 1, 2010 and September 19, 2017. Two groups were established: LD before PCI (LD-PRE) and LD during or after PCI (LD-CATH).

ResultsA total of 4123 patients were included, 66.3% in the LD-PRE group and 32.4% in the LD-CATH group. Prehospital use of a P2Y12 inhibitor was a predictor of the composite bleeding endpoint (major bleeding, need for transfusion or hemoglobin [Hb] drop >2 g/dl), Hb drop >2 g/dl and reinfarction. There were no differences between groups in major adverse events (MAE) (in-hospital mortality, reinfarction and stroke) or in-hospital mortality.

ConclusionsPrehospital use of a P2Y12 inhibitor was associated with an increased risk of bleeding, predicting the composite bleeding outcome and Hb drop>2 g/dl, with no differences in mortality or MAE, calling into question the benefit of this strategy.

No enfarte agudo do miocárdio com supra desnivelamento do segmento ST (EAMcST) é inequívoco o benefício do uso de dupla anti-agregação plaquetar. O tempo ideal para administrar a dose de carga do inibidor do recetor P2Y12 (DC-iP2Y12) é pouco consensual e motivo de debate. O principal objetivo do trabalho foi caracterizar a prática usada em Portugal e avaliar o impacto prognóstico da estratégia de administração da DC-iP2Y12, se antes ou durante/após angioplastia primária (AP).

MétodosEstudo multicêntrico, retrospetivo, baseado no Registo Nacional de Síndromes Coronárias Agudas, com inclusão de doentes com EAMcST e AP realizada de 1/10/2010 a 19/09/2017. Estabelecidos dois grupos: DC-iP2Y12 pré-AP (PRE-DC-iP2Y12) e DC-iP2Y12 durante ou após AP (CAT-DC-iP2Y12).

ResultadosIncluídos 4123 doentes, 66,3% do grupo PRE-DC-iP2Y12 e 32,4% do grupo CAT-DC-iP2Y12. Numa análise multivariada o uso de PRE-DC-iP2Y12 foi preditor de HEMATS (endpoint composto por hemorragia major, transfusão de sangue e queda de hemoglobina (Hb)>2 g/dL), queda de Hb>2 g/dL e re-enfarte. Não se verificaram diferenças entre grupos no MACE (endpoint composto por morte hospitalar, acidente vascular cerebral e re-enfarte) e morte hospitalar.

ConclusõesO uso de PRE-DC-iP2Y12 associou-se a um aumento do risco hemorrágico, sendo preditor do outcome composto de hemorragia (HEMATS) e de queda de Hb>2 g/dL, sem diferenças significativas na mortalidade e no MACE, o que coloca em questão o benefício desta estratégia.

In ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is unequivocal.1,2 For several years, the most widely used P2Y12 inhibitor, with the best supporting evidence, was clopidogrel. However, the results of trials comparing clopidogrel with ticagrelor3 and prasugrel4 have led to the latter two drugs becoming the first-line P2Y12 inhibitors for the treatment of STEMI.1,2

The optimal time to administer the loading dose (LD) of a P2Y12 inhibitor is the subject of considerable debate and disagreement. The Administration of Ticagrelor in the Cath Lab or in the Ambulance for New ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction to Open the Coronary Artery (ATLANTIC) study,5 the only major randomized trial to address the issue, concluded that prehospital administration of ticagrelor is safe, with no increase in bleeding complications, but did not improve coronary perfusion pre-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) compared to ticagrelor administered only in the catheterization laboratory (cath lab). However, the time difference between cath lab and prehospital use of ticagrelor in this trial was only 31 min, which does not reflect the actual timings found in most countries.5

With regard to clopidogrel, there is little evidence that administration before hospital admission is more beneficial than in the cath lab.6–9 Only a single small randomized trial showed a trend (p=0.09) for fewer events (reinfarction, urgent revascularization and death) with pretreatment; the other evidence comes from registries and retrospective studies that show a reduction in mortality with pretreatment.6,8

Based on this evidence, current international guidelines recommend early administration of a P2Y12 inhibitor LD, preferably before hospitalization.1,2

Since real-world practice does not necessarily reflect the conditions of studies and trials, it is important to use actual records to determine the real impact of pretreatment with P2Y12 inhibitors.

ObjectivesThe main aim of this study was to characterize current practice in Portugal regarding the timing of a P2Y12 inhibitor LD (before versus during or after PCI), and to assess the impact of the choice of strategy. Safety was assessed using a composite bleeding endpoint (major bleeding according to the GUSTO definition, need for transfusion or hemoglobin [Hb] drop >2 g/dl), and outcomes were assessed using a composite endpoint of major adverse events (MAE) (in-hospital mortality, reinfarction and stroke).

MethodsStudy designThis was a multicenter retrospective descriptive correlational study based on the Portuguese National Registry on Acute Coronary Syndromes (ProACS) that included all patients diagnosed with STEMI treated by PCI and P2Y12 inhibitor LD between October 1, 2010 and September 19, 2017. Two groups were established: patients treated by LD before PCI (LD-PRE) and patients treated by LD during or after PCI (LD-CATH). We identified predictors of which strategy was used, and assessed the resulting impact on prognosis and safety.

Patient selectionAll patients aged ≥18 years, registered in ProACS between October 1, 2010 and September 19, 2017, diagnosed with STEMI and treated by PCI were included. The diagnosis of STEMI was based on the presence of chest pain or angina equivalent in the previous 48 hours and ST-segment elevation in contiguous leads, according to the definition in the European guidelines.1

Patients missing data required to determine the timing of P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration were excluded.

Data collectionData were collected on demographic characteristics, relevant personal history, cardiovascular risk factors, location of STEMI, means of transport to the hospital, hospital of admission, form of admission, and admission to hospitals without a cath lab. The following timings were calculated: symptoms to first medical contact (FMC), FMC to balloon, symptoms to balloon, and door to balloon. Data were also recorded on admission characteristics, coronary angiography, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and medication prior to and during hospitalization and at hospital discharge. Adverse events during hospital stay (mortality, non-fatal reinfarction and stroke) were recorded, as well as the composite endpoint of these three major adverse events (MAE), major bleeding according to the GUSTO definition, need for transfusion or Hb drop>2 g/dl, and the composite bleeding endpoint of these three events.

Study endpointsThe main aim of the study was to assess the impact on prognosis and safety of using a P2Y12 inhibitor LD before (LD-PRE) versus during or after PCI (LD-CATH). The prognostic endpoint was the composite endpoint of MAE and the safety endpoint was the composite bleeding endpoint.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed of the variables selected for characterization of the sample. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviation and categorical variables are presented numerically as percentages. The two groups were compared in terms of the selected variables, using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Student’s t test for continuous variables. The threshold for statistical significance of correlations was set at 95% for p<0.05. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of the choice of treatment strategy, with statistical significance set at p<0.05, and to identify predictors of prognosis and safety, in which an odds ratio (OR) >1 indicated that LD-CATH was a predictor of this variable and an OR<1 indicated that LD-PRE was a predictor.

The logistic regression model was adjusted for the differences between groups.

ResultsStudy sample and comparison between groupsA total of 6757 patients with STEMI, 5238 of them treated by PCI, were initially selected for the study. Of these, 54 (1.0%) were excluded because they had not received a P2Y12 inhibitor LD, three (0.1%) due to lack of information on P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration, and 1058 (20.2%) due to lack of information on timing of P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration. The final sample thus comprised 4123 patients, 2774 (66.3%) in the LD-PRE group and 1349 (32.4%) in the LD-CATH group.

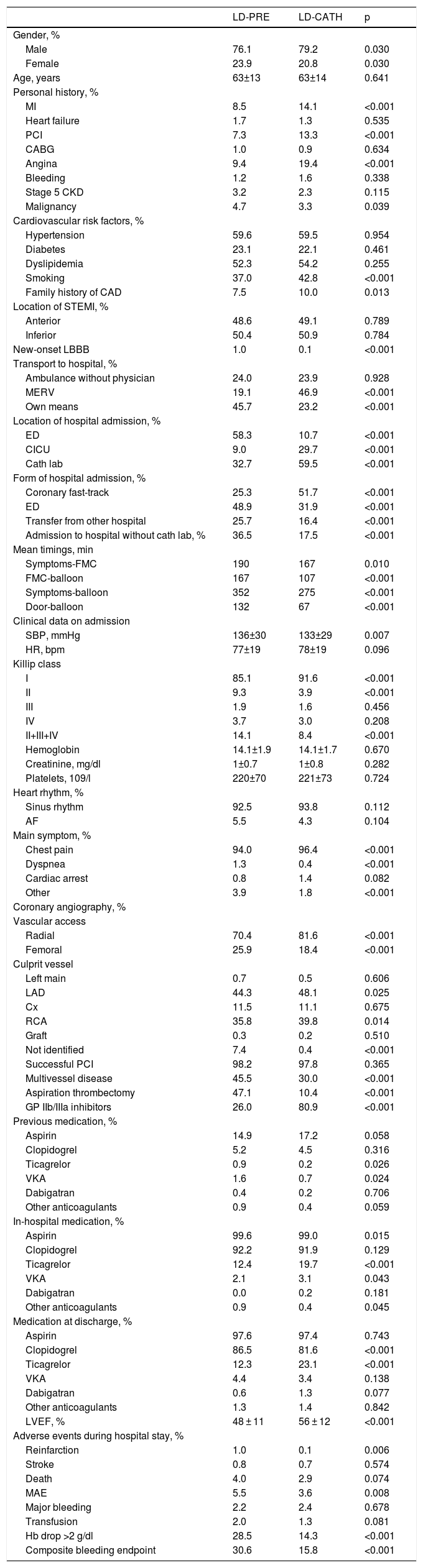

The characteristics of the two study groups are displayed in Table 1.

Characteristics of the two study groups.

| LD-PRE | LD-CATH | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, % | |||

| Male | 76.1 | 79.2 | 0.030 |

| Female | 23.9 | 20.8 | 0.030 |

| Age, years | 63±13 | 63±14 | 0.641 |

| Personal history, % | |||

| MI | 8.5 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.535 |

| PCI | 7.3 | 13.3 | <0.001 |

| CABG | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.634 |

| Angina | 9.4 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.338 |

| Stage 5 CKD | 3.2 | 2.3 | 0.115 |

| Malignancy | 4.7 | 3.3 | 0.039 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, % | |||

| Hypertension | 59.6 | 59.5 | 0.954 |

| Diabetes | 23.1 | 22.1 | 0.461 |

| Dyslipidemia | 52.3 | 54.2 | 0.255 |

| Smoking | 37.0 | 42.8 | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 7.5 | 10.0 | 0.013 |

| Location of STEMI, % | |||

| Anterior | 48.6 | 49.1 | 0.789 |

| Inferior | 50.4 | 50.9 | 0.784 |

| New-onset LBBB | 1.0 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Transport to hospital, % | |||

| Ambulance without physician | 24.0 | 23.9 | 0.928 |

| MERV | 19.1 | 46.9 | <0.001 |

| Own means | 45.7 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| Location of hospital admission, % | |||

| ED | 58.3 | 10.7 | <0.001 |

| CICU | 9.0 | 29.7 | <0.001 |

| Cath lab | 32.7 | 59.5 | <0.001 |

| Form of hospital admission, % | |||

| Coronary fast-track | 25.3 | 51.7 | <0.001 |

| ED | 48.9 | 31.9 | <0.001 |

| Transfer from other hospital | 25.7 | 16.4 | <0.001 |

| Admission to hospital without cath lab, % | 36.5 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Mean timings, min | |||

| Symptoms-FMC | 190 | 167 | 0.010 |

| FMC-balloon | 167 | 107 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms-balloon | 352 | 275 | <0.001 |

| Door-balloon | 132 | 67 | <0.001 |

| Clinical data on admission | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 136±30 | 133±29 | 0.007 |

| HR, bpm | 77±19 | 78±19 | 0.096 |

| Killip class | |||

| I | 85.1 | 91.6 | <0.001 |

| II | 9.3 | 3.9 | <0.001 |

| III | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.456 |

| IV | 3.7 | 3.0 | 0.208 |

| II+III+IV | 14.1 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 14.1±1.9 | 14.1±1.7 | 0.670 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1±0.7 | 1±0.8 | 0.282 |

| Platelets, 109/l | 220±70 | 221±73 | 0.724 |

| Heart rhythm, % | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 92.5 | 93.8 | 0.112 |

| AF | 5.5 | 4.3 | 0.104 |

| Main symptom, % | |||

| Chest pain | 94.0 | 96.4 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 1.3 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.082 |

| Other | 3.9 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Coronary angiography, % | |||

| Vascular access | |||

| Radial | 70.4 | 81.6 | <0.001 |

| Femoral | 25.9 | 18.4 | <0.001 |

| Culprit vessel | |||

| Left main | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.606 |

| LAD | 44.3 | 48.1 | 0.025 |

| Cx | 11.5 | 11.1 | 0.675 |

| RCA | 35.8 | 39.8 | 0.014 |

| Graft | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.510 |

| Not identified | 7.4 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Successful PCI | 98.2 | 97.8 | 0.365 |

| Multivessel disease | 45.5 | 30.0 | <0.001 |

| Aspiration thrombectomy | 47.1 | 10.4 | <0.001 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 26.0 | 80.9 | <0.001 |

| Previous medication, % | |||

| Aspirin | 14.9 | 17.2 | 0.058 |

| Clopidogrel | 5.2 | 4.5 | 0.316 |

| Ticagrelor | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.026 |

| VKA | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.024 |

| Dabigatran | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.706 |

| Other anticoagulants | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.059 |

| In-hospital medication, % | |||

| Aspirin | 99.6 | 99.0 | 0.015 |

| Clopidogrel | 92.2 | 91.9 | 0.129 |

| Ticagrelor | 12.4 | 19.7 | <0.001 |

| VKA | 2.1 | 3.1 | 0.043 |

| Dabigatran | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.181 |

| Other anticoagulants | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.045 |

| Medication at discharge, % | |||

| Aspirin | 97.6 | 97.4 | 0.743 |

| Clopidogrel | 86.5 | 81.6 | <0.001 |

| Ticagrelor | 12.3 | 23.1 | <0.001 |

| VKA | 4.4 | 3.4 | 0.138 |

| Dabigatran | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.077 |

| Other anticoagulants | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.842 |

| LVEF, % | 48 ± 11 | 56 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Adverse events during hospital stay, % | |||

| Reinfarction | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.006 |

| Stroke | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.574 |

| Death | 4.0 | 2.9 | 0.074 |

| MAE | 5.5 | 3.6 | 0.008 |

| Major bleeding | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.678 |

| Transfusion | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.081 |

| Hb drop >2 g/dl | 28.5 | 14.3 | <0.001 |

| Composite bleeding endpoint | 30.6 | 15.8 | <0.001 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; cath lab: catheterization laboratory; CICU: coronary intensive care unit; CKD: chronic kidney disease; Cx: circumflex; ED: emergency department; FMC: first medical contact; GP: glycoprotein; HR: heart rate; LAD: left anterior descending artery; LD-CATH: P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose during or after PCI; LD-PRE: P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose before PCI; LBBB: left bundle branch block; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MAE: major adverse events (in-hospital mortality, reinfarction and stroke); MERV: medical emergency response vehicle; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA: right coronary artery; SBP: systolic blood pressure; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; VKA: vitamin K antagonist.

More patients in the LD-CATH group were male, but mean ages were similar in the two groups. In terms of personal history and cardiovascular risk factors, a history of MI, PCI, angina and smoking and a family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) were more frequent in the LD-CATH group, while a history of malignancy was more frequent in the LD-PRE group. Most patients in the LD-PRE group arrived at the hospital by their own means, while most in the LD-CATH group arrived by medical emergency response vehicle (MERV). The main location of hospital admission in the LD-PRE group was the emergency department (ED), but was the coronary intensive care unit or the cath lab in the LD-CATH group. Arrival via the coronary fast-track system was more likely to be associated with LD-CATH, while LD-PRE was more often associated with admission to a hospital without a cath lab or to the ED.

MI of undetermined location, together with new-onset left bundle branch block (LBBB) and failure to identify the culprit vessel on coronary angiography, were more common in the LD-PRE group. Delays before PCI were shorter in the LD-CATH group. Chest pain as the main symptom was more prevalent in the LD-CATH group. The proportion of patients in Killip class II or higher was greater in the LD-PRE group, while systolic blood pressure (SBP) was lower in the LD-CATH group. Multivessel disease and aspiration thrombectomy were more frequent in the LD-PRE group, and radial access and use of glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitors were more common in the LD-CATH group. Rates of PCI success were similar in the two groups. Regarding medication both during hospital stay and at discharge, ticagrelor was used more by patients in the LD-CATH group, while previous therapy with ticagrelor and vitamin K antagonists was more common in the LD-PRE group.

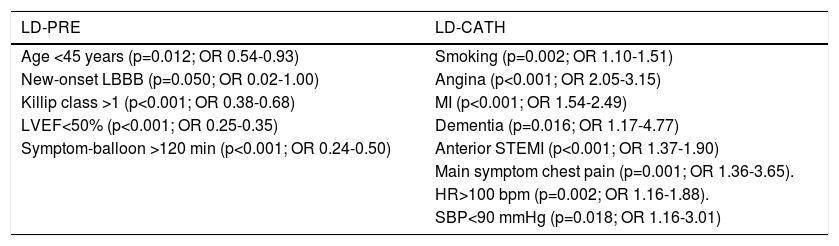

Predictors of the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose administration strategyPredictors of the prehospital use of P2Y12 inhibitor LD were age <45 years, MI of undetermined location with new-onset LBBB, Killip class >1, LVEF<50% and symptom-to-balloon time >120 min. Predictors of the use of P2Y12 inhibitor LD in the cath lab were a history of smoking, angina, MI and dementia, anterior STEMI, chest pain as main symptom, heart rate (HR) >100 bpm, and SBP<90 mmHg (Table 2).

Independent predictors of the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose administration strategy.

| LD-PRE | LD-CATH |

|---|---|

| Age <45 years (p=0.012; OR 0.54-0.93) | Smoking (p=0.002; OR 1.10-1.51) |

| New-onset LBBB (p=0.050; OR 0.02-1.00) | Angina (p<0.001; OR 2.05-3.15) |

| Killip class >1 (p<0.001; OR 0.38-0.68) | MI (p<0.001; OR 1.54-2.49) |

| LVEF<50% (p<0.001; OR 0.25-0.35) | Dementia (p=0.016; OR 1.17-4.77) |

| Symptom-balloon >120 min (p<0.001; OR 0.24-0.50) | Anterior STEMI (p<0.001; OR 1.37-1.90) |

| Main symptom chest pain (p=0.001; OR 1.36-3.65). | |

| HR>100 bpm (p=0.002; OR 1.16-1.88). | |

| SBP<90 mmHg (p=0.018; OR 1.16-3.01) |

HR: heart rate; LD-CATH: P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose during or after PCI; LD-PRE: P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose before PCI; LBBB: left bundle branch block; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction; OR: odds ratio; SBP: systolic blood pressure; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

In terms of prognosis, a simple comparison shows that patients in the LD-PRE group had lower LVEF (48±11% vs. 56±12%, p<0.001) and more reinfarction (1.0% vs. 0.1%, p=0.006), MAE (5.5% vs. 3.6%, p=0.008), Hb drop >2 g/dl (28.5% vs. 14.3%, p<0.001) and the composite bleeding endpoint (30.6% vs. 15.8, p<0.001). No differences were seen in in-hospital mortality, stroke, major bleeding or need for transfusion.

Predictors of the prognostic and safety endpointsThe following factors were identified as predictors of the composite endpoint of MAE: female gender (p=0.003; OR 1.22-2.69), age >75 years (p<0.001; OR 1.78-3.84), HR>100/min (p=0.014; OR 1.12-2.76); SBP<90 mmHg (p<0.001; OR 1.94-5.63), Killip class>I (p<0.001; OR 1.76-4.03), LVEF<40% (p<0.001; OR 2.68-6.33), and multivessel disease (p=0.002; OR 1.24-2.69). The timing of P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration did not predict MAE (p=0.882; OR 0.60-1.54).

Predictors identified for the composite bleeding endpoint were cardiac arrest as main symptom (p=0.005; OR 1.42-7.60), HR > 100/min (p=0.001; OR 1.23-2.12), Killip class>I (p<0.001; OR 1.36-2.33), symptom-to-balloon time >120 min (p<0.001; OR 1.37-2.65), LVEF<40% (p=0.031; OR 1.02-1.64), multivessel disease (p=0.001; OR 1.15-1.68), and prehospital LD (p<0.001; OR 0.37-0.58).

Analysis of the individual endpoints showed that prehospital LD also predicted Hb drop >2 g/dl (p<0.001; OR 0.32-0.51), reinfarction (p=0.03; OR 0.05-0.88), and heart failure (p<0.001; OR 0.39-0.66). The timing of P2Y12 inhibitor administration did not predict major bleeding (p=0.311; OR 0.77-2.25), need for transfusion (p=0.724; OR 0.46-1.71), or death (p=0.652; OR 0.64-2.02).

DiscussionDifferences between groupsConsiderable differences were seen in the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups. Overall, the characteristics of the LD-PRE group appear to indicate a worse prognosis. The clinical history of patients in the LD-CATH group, such as a history of MI, PCI or unstable angina, made a diagnosis of CAD more likely. For the authors of the present paper, this was a somewhat surprising finding, since a stronger suspicion of MI should theoretically be expected to result in earlier use of a P2Y12 inhibitor. This could at least in part be due to the difficulty in establishing a diagnosis of STEMI in a patient with previous CAD and MI, who may present baseline electrocardiographic alterations.10

Concerning the operation and efficiency of the prehospital transport network, patients in the LD-CATH group were more often transported via the coronary fast-track system and by MERV and more often admitted directly to the cath lab, without requiring interhospital transfer, which conferred a prognostic benefit by enabling earlier PCI.11,12 These differences were reflected in shorter symptom-to-balloon time (total ischemic time), which was significantly longer in the LD-PRE group, resulting in a worse prognosis, as shown by their higher rates of MAE.13

Analysis of the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor shows that prasugrel was used in only one patient, while ticagrelor was used more often in the LD-CATH group. This difference may be explained by the fact that ticagrelor was not available for use in MERVs in the first years of our study. Although there was a larger proportion (without statistical significance) of patients in the LD-PRE group who had previously taken ticagrelor, presumably as part of dual antiplatelet therapy, these patients were also more likely to have received a P2Y12 inhibitor before PCI. This is somewhat surprising but is unlikely to have affected the study’s results, as they accounted for fewer than 1% of the overall population. Despite the recommendations in the guidelines to use ticagrelor or prasugrel,1,2 during this period of the study clopidogrel continued to be the most often prescribed P2Y12 inhibitor.

Data from coronary angiography reveal that radial access was used less frequently in patients in the LD-PRE group, who also more often had multivessel disease, two factors that, once again, would indicate a worse prognosis for this group; in addition, use of vascular access other than radial increases bleeding risk.14–16 Aspiration thrombectomy was used much more frequently in the LD-PRE group, which can lead to a higher rate of stroke,17 although this was not observed in our sample. GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used more often in the LD-CATH group, but this did not significantly increase the rate of bleeding complications.

The culprit vessel was not identified in a higher proportion of patients in the LD-PRE group (7.4% vs. 0.4%), which may be related to differential diagnosis with other conditions that have a similar presentation to STEMI, such as myocarditis and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, but are not associated with CAD. When assessed in the cath lab following visualization of the coronary anatomy, these patients were not administered a P2Y12 inhibitor LD, which would explain the difference observed. The timing of P2Y12 inhibitor administration did not affect the PCI success rate, demonstrating that the LD-PRE group received no benefit in this regard.

Finally, in terms of the prognostic and safety endpoints, the LD-PRE group had a greater percentage of events, including higher rates of reinfarction, MAE, Hb drop >2 g/dl and the composite bleeding endpoint, which confirms that the differences described above had a negative effect on prognosis in this group.

Prognostic impact of the choice of loading dose strategyThe ATLANTIC study,5 in which 1862 patients were randomized to receive prehospital (in the ambulance) or in-hospital (in the cath lab) treatment with ticagrelor, set out to determine the best timing for P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration. Efficacy, as measured by, among other endpoints, the proportion of patients with at least 70% resolution of ST-segment elevation at 60 min after PCI and TIMI flow 3 at the end of the procedure, was similar in the two groups. No differences were seen in mortality, stroke or bleeding; the only statistically significant difference was a reduction in stent thrombosis in the prehospital ticagrelor group.

Concerning the use of clopidogrel, there are only a few registries and a single small randomized trial, which suggested a benefit for prehospital LD.6–8 A meta-analysis with a total of 37 814 patients who underwent angioplasty but not necessarily PCI showed that pretreatment with clopidogrel did not change mortality or bleeding rates, but did reduce the number of thrombotic events (MI, stroke and urgent revascularization).18 Another meta-analysis, assessing pretreatment with P2Y12 inhibitors in patients with non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI), found no impact on mortality but a significant increase in bleeding complications,19 while in a non-randomized cardiac magnetic resonance study, pretreatment with clopidogrel was associated with lower prevalence and smaller extent of microvascular obstruction, but no difference in infarct size.9

Regarding prasugrel, a randomized trial in patients with NSTEMI found no benefit from prasugrel pretreatment in terms of prognosis or safety.20

As can be seen, multiple studies have approached this subject but their results have been inconsistent, and it remains to be proved unequivocally whether pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor LD is in fact beneficial. 21 The only randomized trial in patients with STEMI did not demonstrate a benefit of this strategy.5 However, the newer P2Y12 inhibitors have a more rapid onset of action than clopidogrel,22,23 and so studies indicating a benefit from clopidogrel pretreatment may not apply to the newer drugs. A small real-world study of pretreatment with ticagrelor at least 1.5 hours before PCI showed improved TIMI flow grade after PCI but no impact on mortality, stent thrombosis or bleeding.24

In our study, which included 4123 patients with STEMI treated by PCI, multivariate analysis showed that use of a P2Y12 inhibitor LD had no impact on mortality or MAE, and that prehospital treatment increased the risk of reinfarction. The authors consider this latter finding unexpected, since the purpose of administering a P2Y12 inhibitor is to reduce thrombotic events and to improve coronary flow at the time of PCI by inhibiting platelet aggregation earlier. Although in univariate analysis there was a marked increase in MAE in the LD-PRE group, this was not seen in multivariate analysis, in which the worse prognosis in this group was related to the greater number of comorbidities, as stated above, and with longer delays before PCI. With regard to the bleeding endpoints, the composite bleeding endpoint and Hb drop >2 g/dl were more frequent in the LD-PRE group, but major bleeding and need for transfusion were not.

Considerable differences were seen between the groups in radial access, use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors and direct admission to the cath lab (all much more frequent in the LD-CATH group), which, as pointed out above, have important implications for prognosis and bleeding risk. It should be noted that these variables were included in the logistic regression model in order to minimize the differences between the groups and to improve the reliability of the results obtained.

An overall analysis of our results indicates that pretreatment with P2Y12 inhibitors has no prognostic benefit and increases the risk of bleeding complications in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI, implying that this strategy is of little value, which to some extent contradicts the international guidelines.1,2 Our study clearly has significant limitations, but it is in line with others that call the current recommendations into question.5,19,24 It can be seen from our analysis that when considering predictors of the study endpoints, many of the factors that increase thrombotic risk also increase bleeding risk, such as HR>100 bpm, multivessel disease, LVEF<40% and Killip class>I, and these factors were shown to be predictors both of MAE and of the composite bleeding endpoint.

Predictors of the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor loading dose administration strategyAge <45 years, MI of undetermined location with new-onset LBBB, Killip class >1, LVEF<50% and symptom-to-balloon >120 min were predictors of the use of prehospital P2Y12 inhibitor LD. This strategy tended to be used in younger patients, in those with evidence of heart failure (left ventricular dysfunction and worse Killip class) and in those in whom revascularization was expected to occur later.

A history of smoking, angina, MI and dementia, anterior STEMI location, chest pain as main symptom, HR>100 bpm, and SBP<90 mmHg were predictors of P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration in the cath lab. This strategy was preferred in patients with established or probable CAD (those with a history of smoking, angina and MI, and chest pain as main symptom) and in those with anterior MI and greater hemodynamic instability.

In both cases, given the limitations imposed by the retrospective nature of the study, it is difficult to be sure whether these predictors are taken into consideration in decisions concerning the strategy to adopt or are in fact the consequence of the chosen strategy. These findings should therefore be treated with caution.

LimitationsThis study has certain limitations. It was a retrospective study with all the disadvantages and limitations inherent to this study design. The follow-up was short, only up to hospital discharge. There were considerable differences between the groups, most of which benefited the prognosis of the LD-CATH group. Multivariate analysis was accordingly performed in order to minimize these differences, but this reduced the study’s statistical power. Another limitation is the fact that the P2Y12 inhibitor used by most patients in the sample was clopidogrel, whereas the latest guidelines recommend ticagrelor or prasugrel.

Finally, the exact timing of prehospital P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration was not recorded, and therefore the precise differences between timings in the two groups cannot be determined.

ConclusionsIn our population, clopidogrel remained the most widely used P2Y12 inhibitor in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI. The preferred strategy in Portugal, applied to two-thirds of patients, is P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration before PCI.

Pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor LD was preferred in younger patients, in those with evidence of heart failure (left ventricular dysfunction and worse Killip class) and in those in whom revascularization was expected to occur later. Administration only in the cath lab was preferred in patients with anterior MI and hemodynamic instability and in those with an established diagnosis of CAD.

In this study, pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor LD did not affect mortality or MAE, but was a predictor of reinfarction. In the safety assessment, pretreatment was associated with increased bleeding risk, predicting the composite bleeding endpoint and Hb drop >2 g/dl.

The conclusions of this study do not support a benefit of pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor before PCI in real-world patients. These findings have limitations, particularly due to the retrospective nature of the study and the differences between the groups, but they call attention to the need for a large-scale randomized trial that could help define the optimum timing for P2Y12 inhibitor LD administration.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Guedes JPM, Marques N, Azevedo P, Mota T, Bispo J, Fernandes R, et al. Dose de carga do inibidor P2Y12 antes do laboratório de hemodinâmica no enfarte agudo do miocárdio com supra desnivelamento do segmento ST – Será mesmo a melhor estratégia? Rev Port Cardiol. 2020;39:553–561.