A 15-year-old girl was admitted to the cardiology outpatient clinic due to mild palpitations and documented incessant slow ventricular tachycardia (VT) with left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern. The baseline electrocardiogram revealed first-degree atrioventricular block and intraventricular conduction defect. Transthoracic echocardiography showed prominent trabeculae and intertrabecular recesses suggesting left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC), which was confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. During electrophysiological study, a sustained bundle branch reentrant VT with LBBB pattern and cycle length of 480 ms, similar to the clinical tachycardia, was easily and reproducibly inducible. As there was considerable risk of need for chronic ventricular pacing following right bundle ablation, no ablation was attempted and a cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted. To the best of our knowledge, no case reports of BBR-VT as the first manifestation of LVNC have been published. Furthermore, this is an extremely rare presentation of BBR-VT, which is usually a highly malignant arrhythmia.

Uma jovem de quinze anos de idade foi observada em consulta externa de Cardiologia por palpitações ligeiras e documentação de taquicardia ventricular (TV) lenta e incessante com padrão de bloqueio de ramo esquerdo (BRE). O electrocardiograma (ECG) basal revelou bloqueio auriculoventricular (BAV) de primeiro grau e perturbação da condução intraventricular. Um ecocardiograma transtorácico documentou trabeculação proeminente e recessos intertrabeculares, alterações sugestivas de ventrículo esquerdo não-compactado (VENC), diagnóstico confirmado por ressonância magnética cardíaca. No estudo electrofisiológico, uma taquicardia ventricular sustentada por reentrada de ramo, com padrão de BRE e ciclo de base de 480 ms, semelhante à taquicardia clínica, foi repetidamente induzida. Considerando o risco elevado de necessidade de pacing ventricular crónico em caso de ablação do ramo direito (BAV de primeiro grau e BRE no ECG basal e intervalo HV 100 ms no estudo electrofisiológico), não foi efetuado qualquer procedimento ablativo e um cardioversor-desfibrilhador foi implantado. Até ao momento atual, nenhum caso de TV por reentrada de ramo como primeira manifestação de VENC foi publicado. O caso descrito revela uma apresentação extremamente atípica deste tipo de TV, que habitualmente é rápida e maligna.

Bundle branch reentrant ventricular tachycardia (BBR-VT), an uncommon form of macroreentrant tachycardia, generally occurs in the context of dilated cardiomyopathy, previous valve surgery or other cardiac conditions with underlying His-Purkinje system (HPS) disease. This case is a very unusual presentation of BBR-VT in a young patient with isolated left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC). Although our patient presented with HPS disease allowing initiation of this arrhythmia, it is rare for BBR-VT to be the first manifestation of isolated LVNC. Furthermore, BBR-VT is a highly malignant arrhythmia, yet our patient was almost asymptomatic due to the surprisingly long cycle length of the ventricular tachycardia (VT) and despite its unusual incessancy.

Case reportA 15-year-old girl was referred to our arrhythmology department for mild palpitations and documented incessant VT (hemodynamically stable VT lasting hours). She was otherwise healthy, with no relevant medical history and no family history of significant cardiomyopathy or sudden cardiac death (SCD). Her palpitations were not related to effort and were persistent but otherwise extremely well tolerated. She denied precordial pain, dizziness, or presyncope/syncope. A previous electrocardiogram (ECG) had revealed wide-QRS tachycardia (WCT) at 115 beats per minute (bpm).

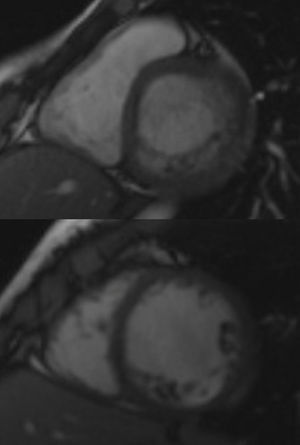

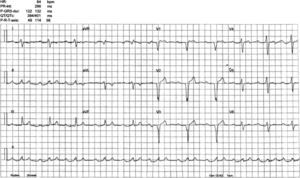

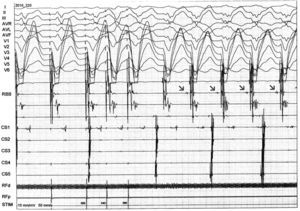

InvestigationsThe patient was examined shortly after being referred, and denied any symptoms, including palpitations. The physical exam was unremarkable. The first ECG showed a VT with left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern and superior axis at 118 bpm. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a normal-sized LV and preserved overall systolic function, hypertrabeculation of the LV posterior and lateral walls and intertrabecular recesses communicating with the LV cavity as demonstrated by color Doppler flow, suggestive of LVNC, which was confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 1). Subsequent ECGs alternated between sinus rhythm with intraventricular conduction abnormalities and first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block and slow VT with LBBB pattern and superior axis (Figure 2).

An exercise stress test was stopped at 3:58 because of the sudden induction of a well tolerated yet sustained slow wide QRS tachycardia with right bundle branch (RBB) and left posterior fascicular block patterns. During most of the recovery time, an incomplete RBB block pattern with right axis deviation was seen, as at the beginning of the test.

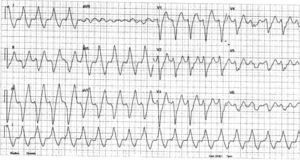

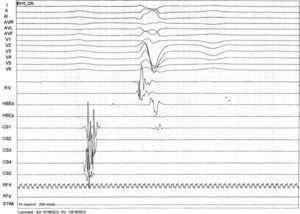

An electrophysiological study (EPS) was performed. The baseline ECG revealed sinus rhythm, intraventricular conduction defects (QRS 122 ms) and significant PR prolongation (296 ms) (Figure 3). A standard protocol using 6-F diagnostic electrophysiology catheters was followed. Two quadripolar catheters were placed in the high right atrium, His bundle and right ventricle as required, and a decapolar catheter in the coronary sinus. The programmed ventricular stimulation protocol included three drive-cycle lengths (CL) and two ventricular extrastimuli while pacing from the right ventricular apex. A 125 bpm-rate monomorphic sustained VT was reproducibly inducible with a single extrastimulus 360 ms after an eight-beat drive-cycle length of 600 ms. It had a LBBB pattern, superior axis and a clear right bundle deflection preceding each ventricular complex, suggesting the RBB was part of the circuit (Figure 4). A short postpacing interval was obtained from the right ventricular apex. Left posterior fascicular block was intermittently seen, associated with an increase in the VT CL, further suggesting a diagnosis of BBR-VT. The VT was exceptionally well tolerated and always terminated by anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) with 380–420 ms CL. A second VT with a slightly different morphology in the limb leads was also inducible. Short periods of intermittent RBB block were documented during sinus rhythm. Further data included AH interval 157 ms; HV interval 100 ms; and Wenckebach period 540 ms (Figure 5).

As there was a considerable risk of need for chronic long-term ventricular pacing following RBB ablation and considering that this VT was particularly slow and practically asymptomatic, ablation of the RBB was not attempted and the patient was referred for implantation of a dual-chamber cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). The rationale for this lay in the spontaneous occurrence of sustained VT, albeit slow, and the easy inducibility of sustained BBR-VT, a highly malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmia that had an unusual presentation in this patient but could nevertheless recur at higher rates. The ICD would protect the patient from potential future episodes of fast VT or ventricular fibrillation and would have additional advantages: (1) ventricular pacing in the event of complete AV block (the patient had significant bilateral bundle branch conduction abnormalities with marked HV prolongation); and (2) quantification of the number and duration of VT episodes in the upcoming months or years. If persistently high heart rates caused by long episodes of VT are observed, especially if associated with deterioration in LV systolic function (tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy), RBB ablation will be considered. In this case, we will then opt for resynchronization.

Outcome and follow-upDuring EPS and ICD implantation, ATP successfully terminated all episodes of VT. The defibrillator was accordingly programmed to deliver ATP for VT CL of 400–500 ms. Termination of episodes of slow VT could help prevent tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. A few hours after implantation, the patient received six shocks in a 2-hour period after failed ATP for relatively slow VT (rate 125 bpm), causing considerable distress to the patient, and ATP was turned off. No further ICD shocks were reported in the following six months and she remains asymptomatic. Several episodes of sustained slow VT have been detected by the ICD.

DiscussionLVNC is a rare form of a primary genetic cardiomyopathy considered to be the result of abnormal intrauterine arrest of the myocardial compaction process.1 Heart failure, arrhythmias (including SCD) and embolic events are its classical triad of complications. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias are reported in 38–47% and SCD in 13–18% of adult patients with LVNC.2

Although 80–90% of LVNC patients show ECG abnormalities, no ECG features are specific to the disease.3 Conversely, intraventricular conduction defects are uncommon in children with LVNC, in whom the most frequent arrhythmias or conduction defects are Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, AV block (mainly second-degree), VT and bradycardia, while adults usually present with LV hypertrophy, LBBB, VT, atrial fibrillation, QT prolongation and AV block.4 Our patient had LBBB type intra/interventricular conduction defect and first-degree AV block. She also had intermittent RBB block, rare in these patients. Alternating bundle branch block is a class I recommendation, level of evidence C, for cardiac pacing according to the European Society of Cardiology and European Heart Rhythm Association guidelines for cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization.

The first comprehensive analysis of electrophysiological (EP) findings in a relatively large cohort of patients with LVNC (n=24) proposed that life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias were likely due to the noncompacted myocardium serving as the arrhythmic substrate. Impaired flow reserve in structurally noncompacted myocardial segments with resultant intermittent ischemia could play an important role. However, in that cohort, sustained monomorphic VT was rarely induced, even with isoproterenol infusion. Non-sustained polymorphic VT was observed more commonly and, while it was believed to be nonspecific, three patients with non-sustained polymorphic VT demonstrated malignant ventricular arrhythmias on follow-up. The authors concluded that no specific clinical, electrocardiographic or echocardiographic finding was predictive of VT inducibility, except for the potential protective effect of younger age and LV ejection fraction above 50%. Nevertheless, their findings suggested a negative EPS could identify a subset of patients at low risk of developing malignant tachyarrhythmias.5

The differential diagnosis of a WCT with a typical LBBB morphology is limited to five entities: supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with fixed LBBB, SVT with functional aberrancy, pre-excited reentrant tachycardias using an atriofascicular accessory pathway as the anterograde limb, SVT with a “bystander” atriofascicular pathway, and BBR-VT. In our patient, the lack of a 1:1 AV relationship excluded a pre-excited reentrant tachycardia using an atriofascicular accessory pathway, while ventricular rate greater than atrial rate strongly suggested a VT (rarely, an AV nodal reentrant tachycardia may present with 2:1 retrograde block, but a longer postpacing interval is typically obtained from the right ventricular apex). Other potential diagnoses were automatic fascicular VT and intramyocardial VT. The former is catecholamine-dependent, not induced with programmed stimulation and shows a variable HV interval in tachycardia, while the latter rarely produces entirely typical RBBB or LBBB patterns on surface ECG and does not depend on a critical delay in the HPS. Therefore, these two diagnoses were considered extremely unlikely.

The diagnosis of BBR-VT was suggested by a number of factors:

- •

The presence of clear intraventricular conduction abnormalities and first-degree AV block on the baseline ECG;

- •

A prolonged baseline HV interval;

- •

The occurrence of a VT with typical LBBB pattern;

- •

The induction and interruption of the arrhythmia with pacing (suggestive of a reentrant mechanism);

- •

The need for a critical conduction delay in the HPS for induction of the tachycardia;

- •

The presence of a clear right bundle deflection preceding each ventricular complex, suggesting the RBB was part of the circuit;

- •

A short postpacing interval from the right ventricular apex.

The current literature contains limited data regarding mapping and ablation of premature ventricular complexes or VT in the presence of LVNC. Fiala et al. described successful ablation of a VT originating in the interventricular septum.6 Derval et al. reported two symptomatic patients who underwent successful radiofrequency ablation of a monomorphic VT in the basolateral aspect of the LV.7 Lim et al. described epicardial ablation of a monomorphic VT located in the epicardial surface of the anterolateral wall.8 The mechanism underlying these arrhythmias is not completely understood. Paparella et al. reconstructed a ventricular electroanatomical mapping in a patient with LVNC and monomorphic VT. No areas of low voltage were identified, probably excluding the presence of scar-based tissue reentry as a possible mechanism.9 There is considerable evidence that most VT episodes in LVNC arise from areas of noncompacted myocardium, and there have been reports that, in some cases, the focus of arrhythmia is not necessarily related to LVNC, indicating the possibility of concomitant idiopathic arrhythmias in this population.10

To the best of our knowledge, no case report of BBR-VT as the first manifestation of LVNC has been published. BBR-VT, an uncommon form of VT incorporating both bundle branches into the reentrant circuit, usually occurs in patients with structural heart disease, mainly dilated cardiomyopathy, although patients with structurally normal hearts have been described. The critical prerequisite for its development is conduction delay in the HPS, which manifests as nonspecific conduction delay or LBBB on the surface ECG and prolonged HV interval in the intracardiac recordings, although some patients may have relatively narrow QRS complexes, suggesting a role of functional conduction delay in the genesis of BBR,11 or even an HV interval within normal limits.12 Patients typically present with presyncope, syncope or SCD because of very rapid rates. QRS morphology during VT is a typical bundle branch block pattern and may be identical to that in sinus rhythm.11

Unlike typical presentations, our patient was practically asymptomatic, reporting mild palpitations despite the incessant nature of her VT (continuing for hours). This lack of symptoms was due to the low rate of the arrhythmia, which is also very unusual for BBR-VT. Preexisting RBB disease or structural cardiac disease (noncompacted myocardium) with more dispersed distal right bundle branches may predispose to such a phenomenon. It may also help explain the occurrence of more than one distinct morphology in BBR-VT utilizing the RBB as the anterograde limb.13 Anterograde conduction occurring in the relative refractory period of a diseased RBB tends to prolong HV interval during VT and could have contributed to its slow and incessant nature.

Regarding the VT documented during stress testing, it could have been a left anterior fascicular VT, an uncommon form of fascicular VT which is often induced by exercise. It could have originated in a small reentry region or through triggered automaticity located in the lateral wall (zone of noncompacted myocardium), close to the anterior fascicle of the LBB. As the patient had incomplete RBB block with right axis deviation before and after the occurrence of the arrhythmia, it might have been a BBR-VT with the left anterior fascicle as the anterograde limb and the RBB as the retrograde one, which would explain the fact that this VT had a similar rate as the one induced in the EP lab at the time of left posterior fascicular block.

Radiofrequency catheter ablation of a bundle branch can cure BBR-VT and is currently regarded as first-line therapy. The technique of choice is ablation of the RBB. The reported incidence of clinically significant conduction system impairment requiring implantation of a permanent pacemaker is 10–30%.11 The decision not to ablate our patient's right bundle was due to: (1) a high probability of need for chronic ventricular pacing (considering the baseline trifascicular conduction disease and HV prolongation); (2) the asymptomatic nature of her arrhythmia; (3) the possibility of periodic reassessment of the potential benefit of RBB ablation for lowering the number of future ICD shocks or preventing tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy; ICD monitoring may quantify the number and duration of VT episodes, which will help in this analysis; and (4) ablation of the RBB could result in the easier induction of a less well tolerated interfascicular reentrant VT, as described in the literature.14

Based on current evidence, patients with severely reduced LV ejection fraction should have an ICD implanted empirically and not undergo EPS for risk stratification. Prophylactic ICD implantation appears reasonable in patients with LVNC who fulfill the SCD-HeFT criteria. Patients with LVNC presenting with symptomatic arrhythmias or syncope are also good candidates for ICD implantation.15

Conclusions- •

In patients with LVNC, VT exit points are usually located in regions of noncompacted myocardium. However, BBR-VT may be the first manifestation of this condition.

- •

BBR-VT is a highly malignant form of VT, often presenting with syncope or SCD. However, in patients with baseline bilateral conduction delay, it may be slow, incessant and exceptionally well tolerated.

- •

Although catheter ablation of BBR-VT involving both bundle branches has a high success rate in preventing new episodes of the arrhythmia, the decision to perform this procedure must be weighed against potential harm. Ablating the RBB in a young patient with LBB block and HV prolongation will likely result in the need for chronic long-term ventricular pacing.

- •

The potential usefulness of programming a low tachycardia detection rate and ATP in patients with a history of slow VT for prevention of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy must be weighed against the possibility of inappropriate detection and treatment of supraventricular tachycardia (very common in patients with LVNC) and the potential acceleration of a possibly asymptomatic VT resulting in a malignant form of VT. In the present case, ATP failed to terminate the slow VT, resulting in several painful shocks. These events suggest treatment of a slow VT should consist of ATP therapy only or no therapy at all, whereas ATP followed by shocks should be programmed only in the conventional VT zone.

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.