Every year cardiovascular disease (CVD) causes 3.9 million deaths in Europe. Portugal has implemented a set of public health policies to tackle CVD mortality: a smoking ban in 2008, a salt reduction regulation in 2010 and the coronary fast-track system (FTS) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in 2007. Our goal in this study was to analyze the impact of these three public health policies in reducing case-fatality rates from ACS between 2000 and 2016.

MethodsThe impact of these policies on monthly ACS case-fatalities was assessed by creating individual models for each of the initiatives and implementing multiple linear regression analysis, using standard methods for interrupted time series. We also implemented segmented regression analysis to test which year showed a significant difference in the case-fatality slopes.

ResultsSeparate modeling showed that the smoking ban (beta=-0.861, p=0.050) and the FTS (beta=-1.27, p=0.003) had an immediate impact after implementation, but did not have a significant impact on ACS trends. The salt reduction regulation did not have a significant impact. For the segmented model, we found significant differences between case-fatality trends before and after 2009, with rates before 2009 showing a steeper decrease.

ConclusionsThe smoking ban and the FTS led to an immediate decrease in case-fatality rates; however, after 2009 no major decrease in case-fatality trends was found. Coronary heart disease constitutes an immense public health problem and it remains essential for decision-makers, public health authorities and the cardiology community to keep working to reduce ACS mortality rates.

A doença cardiovascular (DCV) causa 3,9 milhões de mortes na Europa anualmente. Portugal implementou um conjunto de políticas de saúde pública que abordam a mortalidade por DCV, a lei do tabaco em 2008, a lei de redução do sal em 2010 e a via verde coronária (VVC) em 2007. O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar o impacto destas três políticas de saúde na redução das taxas de letalidade por síndrome coronária aguda (SCA) entre 2000 e 2016.

MétodosO impacto destas políticas na taxa letalidade foi avaliado através da criação de modelos individuais para cada uma das iniciativas. Foi também implementada uma regressão segmentada para testar qual o ano em que houve uma diferença significativa na letalidade.

ResultadosOs modelos individuais mostraram que a lei do tabaco (β=-0,861, p-valor=0,050) e a VVC (β=-1,27, p-valor=0,003) tiveram impacto imediato após a sua implementação. A estratégia de redução do sal não teve impacto significativo. Para o modelo segmentado, encontramos diferenças significativas entre as tendências de letalidade antes e depois de 2009, com taxas anteriores a 2009 mostrando uma queda mais acentuada.

ConclusãoA lei do tabaco e a VVC levaram a uma diminuição imediata da taxa de letalidade; no entanto, depois de 2009, não houve redução significativa. A doença coronária constitui um grande problema de saúde pública, é crítico que as autoridades de saúde pública e a comunidade de cardiologia continuem a trabalhar para reduzir as taxas de mortalidade por SCA.

Every year cardiovascular disease (CVD) causes 3.9 million deaths in Europe and over 1.8 million deaths in the European Union (EU), accounting for 37% of all deaths in the EU.1 In Portugal and in Europe as a whole, CVD is the leading cause of death.2

Despite recent decreases in mortality rates in many countries, CVD is still responsible for almost half of all deaths in Europe,2 and constitutes a major public health challenge in western Europe.3

Of all behavioral components, dietary factors pose the greatest risk for CVD mortality and reduced CVD disability-adjusted life years in the European population. High systolic blood pressure and smoking represent other major risk factors.

Several European countries have implemented measures to tackle CVD mortality, from disease prevention by tackling major risk factors to improvements in disease management and treatment.

As part of this effort, in recent years Portugal has instituted a set of health policies that directly or indirectly tackle CVD mortality, including a smoking ban in 2009, a salt reduction regulation in 2010 and the coronary fast-track system (FTS) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The latter policy, which was more directed linked to reducing mortality, was launched in 2000, but was not fully implemented throughout the country until 2007.

There is growing evidence-based data worldwide on the effectiveness of these health policies and public health initiatives; however, reports on the effectiveness of similar policies in Portugal is scarce. More importantly, there has been no analysis of the cumulative effect of the three major polices recently implemented in Portugal. In the context of increasingly limited resources for health care, investment in population-wide policy strategies needs to show an appropriate return, in this case a decline in CVD mortality. It is therefore important to assess the influence of these policies on observed coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality.

Our aim was thus to analyze the impact of the three health policies implemented in Portugal in reducing ACS case-fatality rates, namely the FTS for primary angioplasty, the smoking ban and the salt reduction regulation, using case-fatality rates from 2000 to 2016.

MethodsDataData were obtained from the national Diagnosis-Related Group database, which collects information on all admissions to public hospitals in mainland Portugal, including primary diagnosis, demographic variables such as gender and age, and the geographic region of the admission.4 Approval to access the data was previously obtained from the Ministry of Health.

All admissions between 2002 and 2016 of individuals ≥20 years of age with a primary diagnosis of ACS, as coded by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), were extracted. Codes 410.00-410.xx were used to identify admission diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and 413 codes were used to identify unstable angina. All participants with missing data were excluded from the analysis.

Health policies and public health initiativesCoronary fast-track systemThe FTS was implemented in all regions of Portugal by 2007. We therefore had available for analysis seven years of data before the implementation of the regulation (January 2000-December 2007) and nine years of data after implementation (January 2008-December 2016).

The aim of the FTS was to create a priority system that would facilitate access to clinical, therapeutic and diagnostic resources for ACS patients. Direct admission to the catheterization laboratory for primary angioplasty is essential since the time between symptom onset and treatment in MI is crucial to reducing morbidity and mortality. The system is triggered by patients calling the emergency number (112). The National Institute for Emergency Medicine (INEM) can then initiate diagnosis and treatment earlier by transferring the patient to a hospital unit specializing in ACS treatment.5

INEM has the capacity to intervene early, and after clinical diagnosis and electrocardiogram, decides jointly with the Referral Center for Emergency Patients (CODU) on pre-hospital treatment and hospital referral, increasing the likelihood of therapeutic success. CODU contacts the hospital unit to organize the patient's admission and treatment.6

Smoking banThe smoking ban was implemented in January 2008. We therefore had available for analysis six years of data before the implementation of the ban (January 2002-December 2007) and nine years of data after implementation (January 2008-December 2016).

Portugal is a signatory of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control,7 which led to implementation in January 2008 of the most recent anti-smoking measure, Law no. 37/2007.8 This legislation introduced a new framework to protect individuals from passive (second-hand) smoking and to promote smoking reduction and cessation.8,9 The law banned smoking in all enclosed public places, including hospitals, public transport, and workplaces. In addition, it established further regulations regarding information provided on tobacco products, their packaging and labeling, as well as further restrictions on advertising.10

Salt reduction policyThe salt reduction policy was implemented in September 2010. We therefore had available for analysis eight years of data before the implementation of the regulation (January 2002-September 2010) and six years of data after implementation (October 2010-December 2016).

Even small reductions in the prevalence of high blood pressure can lead to major health gains. In view of the importance of these approaches, the WHO created a set of recommendations to reduce dietary salt intake to 5 g/day, in order to prevent chronic disease and improve health.11 In the WHO European Region, 26 out of the 53 member states, including Portugal, have implemented operational salt reduction policies, including those aimed at reducing salt intake.

Notably, bread accounts for about one-sixth of daily salt intake,12,13 with Portugal, Poland and Japan having the highest levels of salt in bread.14,15 The policy introduced in Portugal aimed to reduce salt to 1.4 g per 100 g bread. It also mandated clear salt content labeling of packaged products.

Statistical analysisThe main outcome in our study was monthly case-fatality rates, subsequently stratified by age and gender.

ACS case-fatality rates were calculated for each month, using the total number of patients admitted to public hospitals as the denominator and the number of ACS deaths as the numerator.

The impact of the three policies was studied individually, using a binary covariable indicating the start of the policy, as well as a continuous covariable to account for the effect of the policy after its implementation. A segmented multiple linear regression model was implemented to assess changes over time. These models are useful when the relationship between the response and the independent variables is piecewise linear, i.e. represented by two or more straight lines connected at unknown values (breakpoints).16 In this study, the segmented model was implemented to test for significant changes in case-fatality rates after the introduction of the three policies. The Davies test was used to assess whether the differences between the slopes before and after the breakpoint were significant. The model was fitted in R version 2.5.1 software using the “segmented” library.17

For all models created, the case-fatality rate was the response variable. Four models were created in total, one for each of the policies and one used subsequently to test which year showed a significant difference in case-fatality rate.

All analyses were stratified by gender and age. Two age categories were used, <65 and ≥65 years. Short-term autocorrelation between monthly estimates was incorporated into the model by applying a first-order autoregressive process to the residuals.

Although we were aware that there might be short-term temporal differences in case-fatality rates, related for example to the day of the week, or weekends vs. weekdays, we did not adjust for this in our models. Other studies have shown a steady reduction in differences between weekends and weekdays in the time of CVD events.18 There have also been studies showing that after accounting for mode of arrival at the hospital, there was no difference in case-fatality rates between weekdays and weekends.19

Statistical significance was assessed through p-values, assuming <5% as significant, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each of the regression coefficients. Models were fitted in R software, version 2.5.1.

ResultsA total of 20 849 in-hospital deaths from ACS were recorded in mainland Portugal from 2000 to 2016, out of a total of 203 040 admissions for ACS.

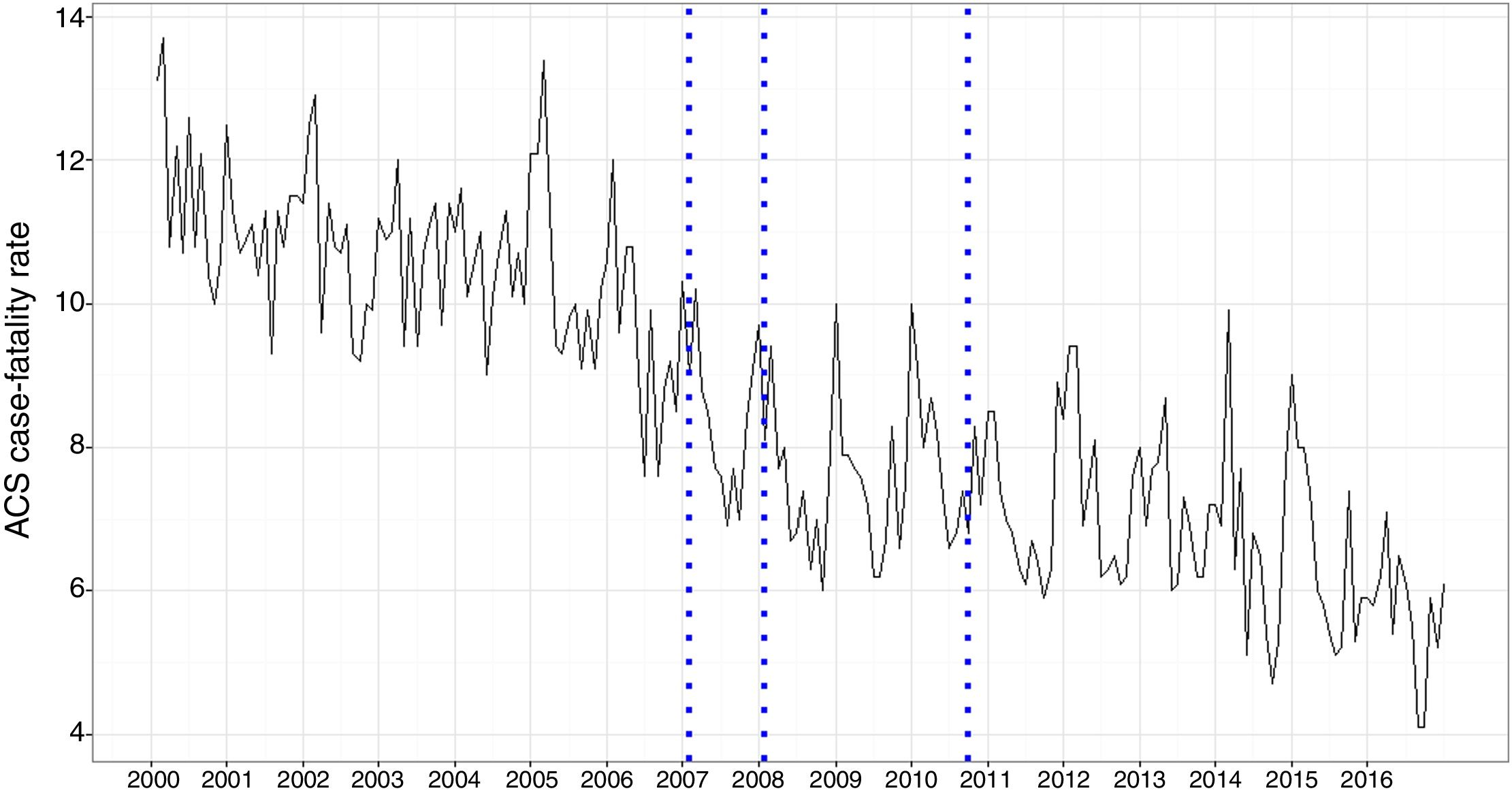

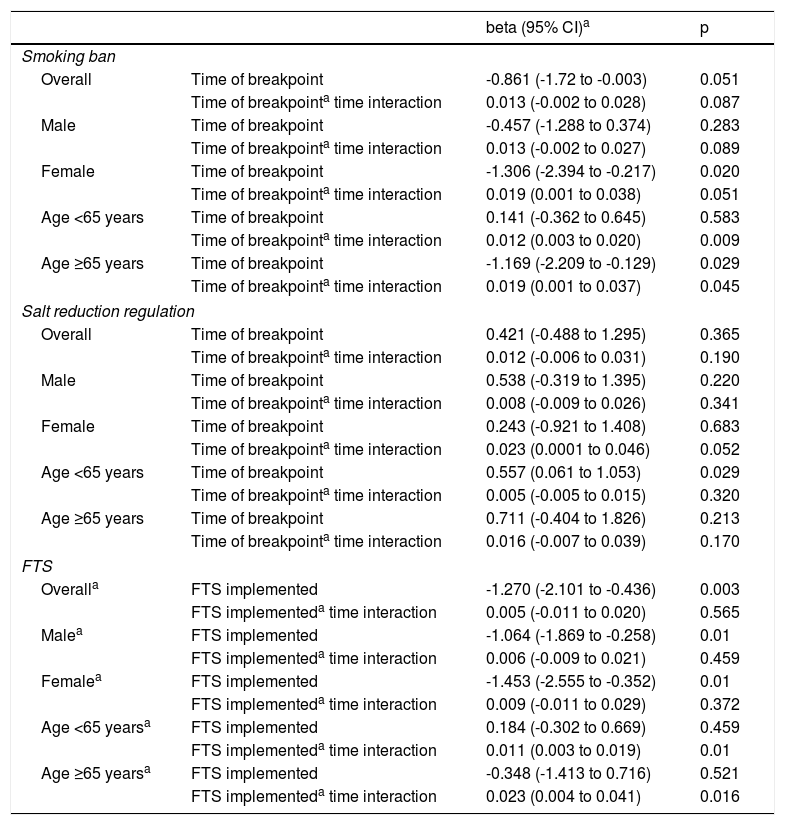

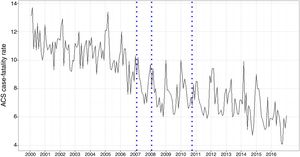

Of the models created individually, one for each policy, the FTS showed an immediate decrease in case fatalities (beta=-1.27, p=0.003); however, it did not impact case-fatality trends after 2007, which remained steady. Similarly, the smoking ban resulted in an immediate decrease in case fatalities after its implementation (p=-0.861, p=0.05), but no significant decrease in trends was observed after 2008 (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Results of segmented linear regression analyses for each of the models for the individual policies.

| beta (95% CI)a | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking ban | |||

| Overall | Time of breakpoint | -0.861 (-1.72 to -0.003) | 0.051 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.013 (-0.002 to 0.028) | 0.087 | |

| Male | Time of breakpoint | -0.457 (-1.288 to 0.374) | 0.283 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.013 (-0.002 to 0.027) | 0.089 | |

| Female | Time of breakpoint | -1.306 (-2.394 to -0.217) | 0.020 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.019 (0.001 to 0.038) | 0.051 | |

| Age <65 years | Time of breakpoint | 0.141 (-0.362 to 0.645) | 0.583 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.012 (0.003 to 0.020) | 0.009 | |

| Age ≥65 years | Time of breakpoint | -1.169 (-2.209 to -0.129) | 0.029 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.019 (0.001 to 0.037) | 0.045 | |

| Salt reduction regulation | |||

| Overall | Time of breakpoint | 0.421 (-0.488 to 1.295) | 0.365 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.012 (-0.006 to 0.031) | 0.190 | |

| Male | Time of breakpoint | 0.538 (-0.319 to 1.395) | 0.220 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.008 (-0.009 to 0.026) | 0.341 | |

| Female | Time of breakpoint | 0.243 (-0.921 to 1.408) | 0.683 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.023 (0.0001 to 0.046) | 0.052 | |

| Age <65 years | Time of breakpoint | 0.557 (0.061 to 1.053) | 0.029 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.005 (-0.005 to 0.015) | 0.320 | |

| Age ≥65 years | Time of breakpoint | 0.711 (-0.404 to 1.826) | 0.213 |

| Time of breakpointa time interaction | 0.016 (-0.007 to 0.039) | 0.170 | |

| FTS | |||

| Overalla | FTS implemented | -1.270 (-2.101 to -0.436) | 0.003 |

| FTS implementeda time interaction | 0.005 (-0.011 to 0.020) | 0.565 | |

| Malea | FTS implemented | -1.064 (-1.869 to -0.258) | 0.01 |

| FTS implementeda time interaction | 0.006 (-0.009 to 0.021) | 0.459 | |

| Femalea | FTS implemented | -1.453 (-2.555 to -0.352) | 0.01 |

| FTS implementeda time interaction | 0.009 (-0.011 to 0.029) | 0.372 | |

| Age <65 yearsa | FTS implemented | 0.184 (-0.302 to 0.669) | 0.459 |

| FTS implementeda time interaction | 0.011 (0.003 to 0.019) | 0.01 | |

| Age ≥65 yearsa | FTS implemented | -0.348 (-1.413 to 0.716) | 0.521 |

| FTS implementeda time interaction | 0.023 (0.004 to 0.041) | 0.016 | |

Longitudinal trends for case-fatality rates from acute coronary syndrome (percentages) for January 2000-December 2016. The vertical lines mark when the coronary fast-track system was fully implemented throughout Portugal (2007), the implementation of the smoking ban (2008), and the implementation of the salt reduction regulation (mid-2010). ACS: acute coronary syndrome.

By contrast, the salt reduction policy did not have any significant effect on case fatalities (beta=0.012, p=0.189), or any immediate impact after its implementation (beta=0.421, p=0.365; Table 1).

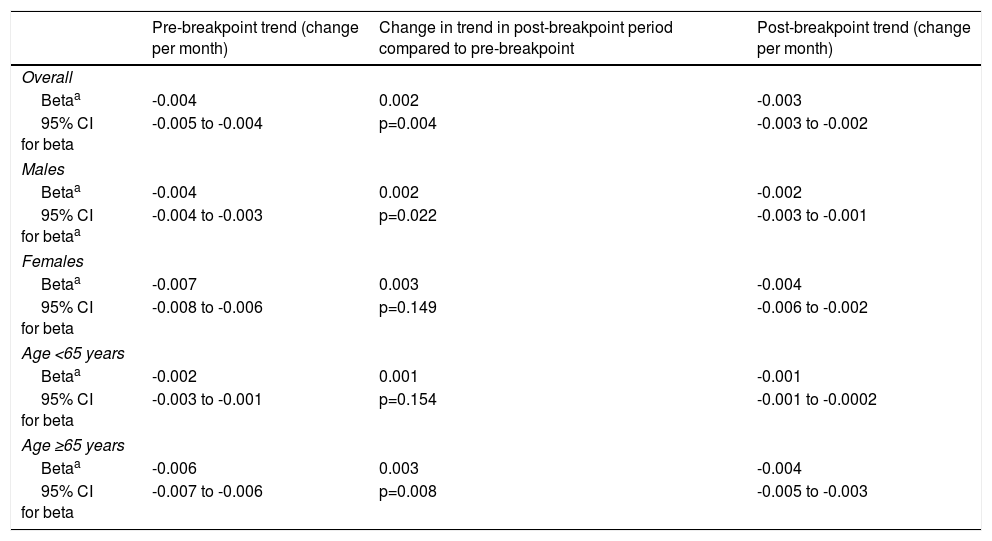

Using a model applying segmented regression, 2009 was identified as a year in which there was a difference in case-fatality rates. Slope trends both before (beta=-0.004; 95% CI -0.005 to -0.004) and after 2009 (p=-0.003; 95% CI -0.003 to -0.002) showed a decrease; however, after 2009 this was less pronounced (beta=0.002, p=0.004) (Table 2).

Results of segmented linear regression analyses in which 2009 was found to be the breakpoint for differences in slopes. Results stratified by gender and age group are also included.

| Pre-breakpoint trend (change per month) | Change in trend in post-breakpoint period compared to pre-breakpoint | Post-breakpoint trend (change per month) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Betaa | -0.004 | 0.002 | -0.003 |

| 95% CI for beta | -0.005 to -0.004 | p=0.004 | -0.003 to -0.002 |

| Males | |||

| Betaa | -0.004 | 0.002 | -0.002 |

| 95% CI for betaa | -0.004 to -0.003 | p=0.022 | -0.003 to -0.001 |

| Females | |||

| Betaa | -0.007 | 0.003 | -0.004 |

| 95% CI for beta | -0.008 to -0.006 | p=0.149 | -0.006 to -0.002 |

| Age <65 years | |||

| Betaa | -0.002 | 0.001 | -0.001 |

| 95% CI for beta | -0.003 to -0.001 | p=0.154 | -0.001 to -0.0002 |

| Age ≥65 years | |||

| Betaa | -0.006 | 0.003 | -0.004 |

| 95% CI for beta | -0.007 to -0.006 | p=0.008 | -0.005 to -0.003 |

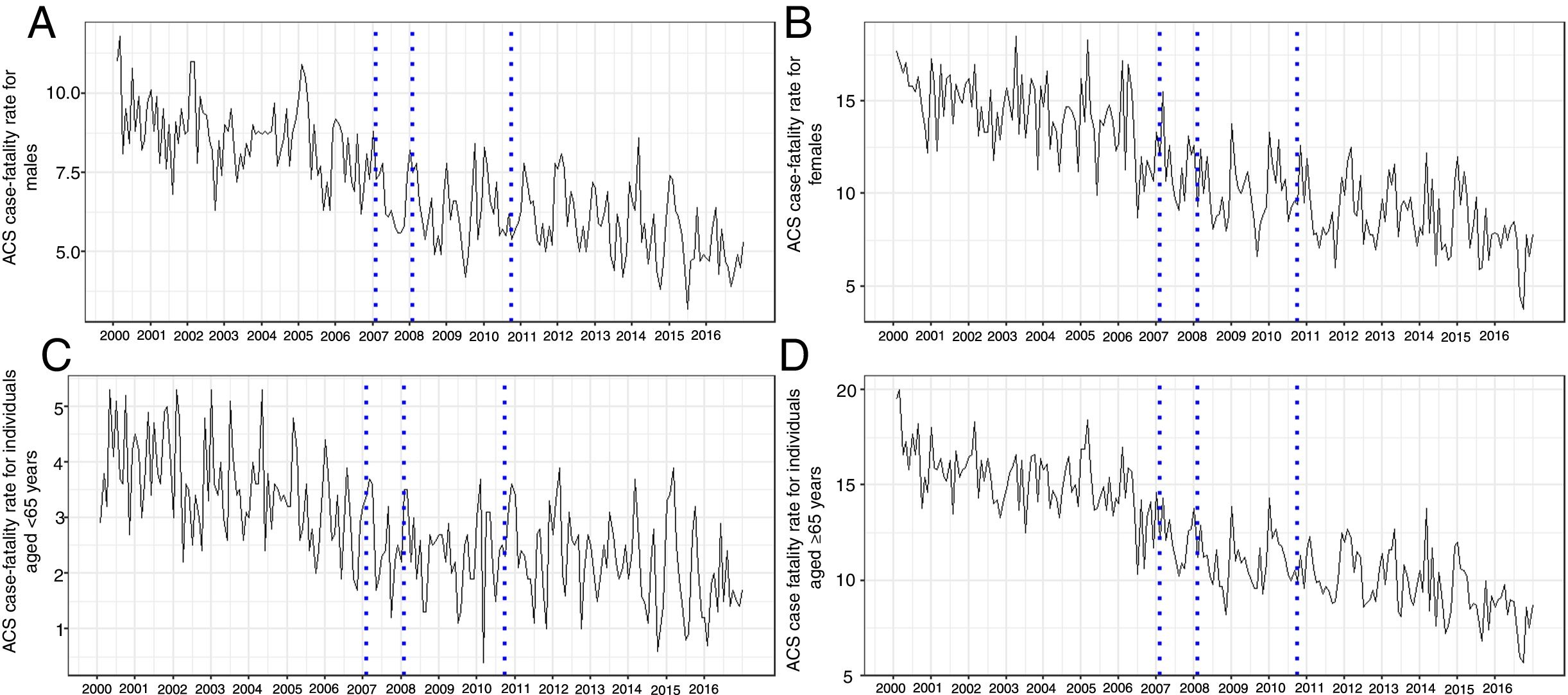

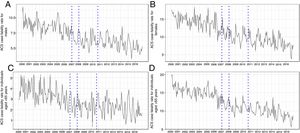

All four models were stratified for ACS case-fatality rates by gender and age. For females (beta=-1.306, p=0.020) and individuals aged ≥65 years (beta=-1.169, p=0.029), there was a significant decrease in case-fatality rates after the smoking ban. For the FTS, both sexes presented a significant decrease in case-fatality rates; however, there was no difference in trends between age groups (Figure 2).

Gender- and age-stratified longitudinal trends for case-fatality rates from acute coronary syndrome (percentage) for January 2000-December 2016. (A) Males; (B) females; (C) individuals aged <65 years; (D) individuals aged ≥65 years. The vertical lines mark the years the policies were implemented. ACS: acute coronary syndrome.

In the segmented model, the year found to have a differential rate of case fatalities was consistent with the model including all the data (2009). Both trends, before and after 2009, were decreasing, though after 2009 the decrease was not as marked as for the period before 2009, as observed for the model including all the patients.

The differences in case-fatality rates before and after 2009 were higher for women (beta=0.003, p=0.029) than for men, and for individuals aged ≥65 years (beta=0.003, p=0.008; Table 2).

The seasonal pattern was consistent with that reported elsewhere,20 with higher admission rates in winter and lower rates during the summer.

DiscussionIn the last 11 years, a set of health policies have been implemented in Portugal to help decrease CVD mortality. The first initiative was the FTS in 2007, followed by the smoking ban in 2008 and the salt reduction regulation in mid-2010.

We created a series of statistical models, four to assess the individual impact of each of the policies, and then one to determine if there was any year during the study that could indicate a difference between trends, suggesting a possible impact of the policies in the country.

The FTS and the smoking ban led to an immediate decrease in case-fatality rates. Previous national and international studies have shown that an FTS, by substantially shortening the time between symptom onset and treatment, directly influences survival. It has been demonstrated that a symptom onset-treatment time of more than 120 min leads to increased in-hospital mortality in an almost linear fashion.21–23 However, the FTS in Portugal is mainly aimed at ST-elevation MI, which accounts for around 40% of all ACS, and so it would not be expected to affect non-ST-elevation MI, meaning that around 60% of ACS patients are not covered by this service.

The relationship between smoking and CVD mortality has been extensively demonstrated. Smoking worsens atherosclerotic alterations, including narrowing the vascular lumen and inducing a hypercoagulable state. Such changes increase the risk of acute thrombosis and thus mortality.24 The results of the current study were very encouraging regarding the smoking ban, as an immediate decrease in case fatalities was found after the ban was implemented. Since the ban targets both smokers and those exposed to second-hand smoke, case-fatality rates should decrease for both groups. Smoking cessation, and even small reductions in consumption, have been linked to decreases in CVD events and in mortality.25

Few studies have analyzed the effect of tobacco control on CVD mortality. Of those available, most focus on how regulations affect hospital admissions26; however, the impact on mortality is equally important. Nevertheless, we are not the first to analyze the impact on mortality. A recent study similarly found a reduction of up to 11% in MI mortality one year after a smoking ban was implemented.27 Another study found a 13% decrease in all-cause mortality, with a decrease of up to 26% in ischemic heart disease (IHD) mortality.

In the current study, we found that 2009 was a breakpoint in our observed trends, which supported the results from the individual models. Up to 2009 the trends were significantly impacted by the policies, leading to a significant decrease in case-fatality rates. After that year, although the trend continued to decrease it was less marked. The impact of the salt regulation in mid-2010 showed a similar effect, with no change in trends after that year. A similar pattern was observed when the impact of this policy on ACS admissions was analyzed.28

We hypothesised that although the salt regulation was an important initiative, it was highly dependent on individual adherence. The way the regulation was implemented may not have produced the desired effect on the population, perhaps due to the low level of health literacy observed in Portugal, and the fact that the policy envisioned a maximum salt content of bread of 1.4 g of salt per 100 g of bread, while other countries set lower limits.

When stratified by gender and age, our results showed that the smoking ban led to an immediate decrease in case-fatality rates for women and individuals aged ≥65 years. Although the number of women who smoke has increased in recent years, the number of men smoking was even higher, and their length of time smoking was also greater. As a consequence, men will have increased mortality from CVD, even if they quit smoking or reduce their tobacco consumption. Older people are more vulnerable to exposure to second-hand smoke, and so reducing it could lead to a decrease in case-fatalities in this group. Our findings were also consistent with another study in which post-ban reductions in IHD mortality were seen in those aged ≥65 years, but not in younger subjects.29

Analyzing the impact of the FTS by groups, we found similarly decreasing case-fatality rates for men and women, an effect previously observed in other studies in which the rate of decrease in CHD mortality was similar in both sexes.30 In addition, no immediate change in case-fatality rates was observed after implementation of the FTS for either younger or older patients. For both groups, there were significant changes in trend; however, the trends observed were increasing. The prevalence of obesity and diabetes31 is rising in Portugal, which could have weakened any reduction in the younger group. This effect has been observed in other studies30,32 in which increases in obesity lead to lower reductions in mortality for younger groups. A similar pattern was observed for the older group, which has previously been found in other datasets.32

Our results for age stratification when using segmented regression showed significant differences between trends before and after 2009, for females and older subjects. As for the non-stratified model, the decrease in trends observed before 2009 was steeper than the decrease observed afterward. These results were consistent with those observed when studying the smoking ban with age stratification, in which a significant decrease in case-fatality rates was observed for older but not for younger individuals. For the gender stratification, although the FTS analysis showed a significant decrease after 2007 for men, this was an immediate effect and not a trend.

LimitationsAs in any ecological study, it is not possible to directly prove any association between policy implementation and the reduction in case-fatality rates from ACS.

One of the strengths of our study is the use of a well-validated and standardized database, enabling easy comparison with other studies in different countries, particularly in other European countries. In addition to the availability of information on gender and age, this enabled us to assess the robustness of our findings among different subgroups. The time-series method is preferred over the simpler pre- and post-proportion comparison method, because it does not take pre-intervention trends into account and also enables corrections to be made for autocorrelation.33

ConclusionsThis study extends the existing literature on the patterns of ACS mortality over time, and assesses whether public health interventions to reduce mortality by ACS were successful. Furthermore, it indicates that to decrease case-fatality rates a multifactorial strategy was needed, rather than a single approach.

Strategies such as the smoking ban and the FTS led to an immediate decrease in case-fatality rates; however, after 2009 no major decreases in ACS trends were found.

Considering that CHD constitutes an immense public health problem,34 it is crucial for different stakeholders, including decision-makers, public health authorities, medical societies and the cardiology community, to keep working together to reduce ACS mortality rates.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.