Major bleeding is a serious complication of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and is associated with a worse prognosis. The CRUSADE bleeding score is used to stratify the risk of major bleeding in ACS.

ObjectiveTo assess the predictive ability of the CRUSADE score in a contemporary ACS population.

MethodsIn a single-center retrospective study of 2818 patients admitted with ACS, the CRUSADE score was calculated for each patient and its discrimination and goodness of fit were assessed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, respectively. Predictors of in-hospital major bleeding (IHMB) were determined.

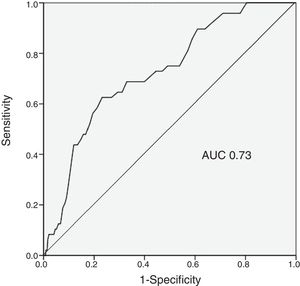

ResultsThe IHMB rate was 1.8%, significantly lower than predicted by the CRUSADE score (7.1%, p<0.001). The incidence of IHMB was 0.5% in the very low risk category (rate predicted by the score 3.1%), 1.5% in the low risk category (5.5%), 1.6% in the moderate risk category (8.6%), 5.5% in the high risk category (11.9%), and 4.4% in the very high risk category (19.5%). The predictive ability of the CRUSADE score for IHMB was only moderate (AUC 0.73).

The in-hospital mortality rate was 4.0%. Advanced age (p=0.027), femoral vascular access (p=0.004), higher heart rate (p=0.047) and ticagrelor use (p=0.027) were independent predictors of IHMB.

ConclusionsThe CRUSADE score, although presenting some discriminatory power, significantly overestimated the IHMB rate, especially in patients at higher risk. These results question whether the CRUSADE score should continue to be used in the stratification of ACS.

A hemorragia major (HM) é uma complicação grave da síndrome coronária aguda (SCA) e está associada a pior prognóstico. O score CRUSADE permite estratificar o risco de HM na SCA.

ObjetivoAvaliar a capacidade preditiva do score CRUSADE numa população contemporânea de SCA.

MétodosEstudo unicêntrico e retrospetivo com 2.818 doentes admitidos por SCA. O score CRUSADE foi calculado para cada doente, a sua discriminação e calibração foram avaliadas pela área abaixo da curva (AUC) Receiver Operating Characteristic e pelo teste Hosmer-Lemeshow, respetivamente. Foram determinados os preditores de HM intra-hospitalar (HMIH).

ResultadosA taxa de HMIH foi de 1.8%, valor significativamente inferior ao estimado pelo score CRUSADE (7,1%, p<0,001). A incidência de HMIH nas diferentes categorias foi de 0,5% na de muito baixo risco (taxa estimada pelo score de 3,1%); 1,5% na de baixo (estimada de 5,5%); 1,6% na de moderado (estimada de 8,6%); 5,5% na de elevado (estimada de 11,9%) e 4,4% na de muito elevado (estimada de 19,5%). A capacidade preditora do score CRUSADE para HMIH foi apenas moderada (AUC 0,73). A taxa de mortalidade intra-hospitalar foi de 4,0%. A idade mais avançada (p=0,027), o acesso vascular femoral (p=0,004), a frequência cardíaca mais elevada (p=0,047) e o ticagrelor (p=0,027) foram preditores independentes de HMIH.

ConclusãoO score CRUSADE, apesar de apresentar algum poder discriminatório, sobrestimou de forma significativa a taxa de HMIH, principalmente nos doentes de maior risco. Esses resultados questionam se o score CRUSADE deverá continuar a ser usado na estratificação da SCA.

acute coronary syndrome

area under the curve

coronary artery bypass grafting

confidence interval

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

glycoprotein

in-hospital major bleeding

left ventricular ejection fraction

myocardial infarction

odds ratio

percutaneous coronary intervention

Patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are a heterogeneous population, with varying levels of risk for events, and so initial assessment has a crucial role in deciding the most appropriate therapeutic strategy.1 Treatment of these patients includes antithrombotic therapy and invasive procedures, which carry an increased risk of bleeding,2 the incidence of which ranges between 1% and 10%.3 This variability in the incidence of bleeding complications is due to various factors, including differences in patient characteristics, concomitant treatment and definitions of bleeding.3 Nevertheless, whatever definition is used, multiple studies have shown that bleeding complications are associated with adverse events including death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and stent thrombosis.3–5

Assessment of the risk of bleeding includes a detailed history of bleeding symptoms, identification of predisposing comorbidities, laboratory data, and calculation of a bleeding risk score.6

The CRUSADE score7 was developed to assess bleeding risk based on a varied population of patients with non-ST-elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS), and was subsequently validated for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).8 It is calculated from eight variables that include baseline characteristics, clinical variables and admission laboratory values.7 It is currently the most commonly used score to determine bleeding risk, due to its proven discriminatory power.6,9,10

The main purpose of the CRUSADE score is to stratify bleeding risk in patients with ACS, in order to select appropriate therapeutic strategies that will reduce bleeding events and hence improve prognosis.9

The aim of this study is to analyze the applicability of the CRUSADE score in ACS patients, in light of the significant changes that have taken place over the last decade in the management and treatment of these patients.

MethodsStudy designThis was a retrospective, descriptive, correlational study of patients admitted with a diagnosis of ACS to the cardiology department of Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Algarve between October 1, 2010 and August 31, 2014. The CRUSADE score was calculated for each patient and its ability to predict in-hospital major bleeding (IHMB) was assessed. Predictors of IHMB were determined.

Patient selectionA total of 2818 patients diagnosed with ACS in the previous 48 hours were included. MI was diagnosed in the presence of chest pain or anginal equivalent in the previous 48 hours together with ischemic electrocardiographic changes (ST-segment deviation or negative T waves) and elevation of troponin levels above the reference value. Unstable angina was defined as the presence of chest pain or anginal equivalent with or without with ischemic electrocardiographic changes in the absence of elevation of troponin levels above the reference value.

Patients with MI associated with revascularization procedures (types 4 and 5) or type 2 MI according to the ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF universal definition of myocardial infarction11 were excluded.

In the analysis of the predictive ability of the CRUSADE score, 203 of the 2818 patients (7.2%) were excluded due to inability to calculate the score.

Data collectionData were collected on demographics (age and gender), relevant personal history (MI, heart failure, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], coronary artery bypass graft surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and cancer), and cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and smoking status). Data were also analyzed on hospital stay, including clinical parameters at admission (systolic blood pressure, heart rate and hematocrit), coronary angiography (vascular access and PCI), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), type of ACS (STEMI, non-ST-segment MI [NSTEMI], MI of undetermined location, or unstable angina), and medication (aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, enoxaparin, unfractionated heparin, warfarin, and glycoprotein [GP] IIb/IIIa inhibitors).

Creatinine clearance was estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula.12

Vascular disease was identified on the basis of a history of peripheral arterial disease and/or stroke.

In-hospital mortality was defined as death from any cause during hospitalization for ACS.

Study objectivesThe study objectives were assessment of the predictive ability of the CRUSADE score for in-hospital major bleeding (IHMB) and determination of independent predictors of IHMB.

IHMB was defined according to the GUSTO classification as intracerebral bleeding or bleeding resulting in hemodynamic compromise requiring treatment.13 The CRUSADE score was calculated from eight variables (baseline hematocrit, estimated creatinine clearance, baseline heart rate, baseline systolic blood pressure, gender, signs of heart failure on presentation, prior vascular disease, and diabetes). The five bleeding risk categories defined by the CRUSADE investigators were used: very low risk (score ≤20), low risk (21-30), moderate risk (31-40), high risk (41-50), and very high risk (>50).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed to characterize the study sample. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as number (percentage).

The predictive ability of the CRUSADE score in our population was tested using the area under the curve (AUC) on receiver operating characteristic analysis14 and the model's goodness of fit was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test,15 in which adequate goodness of fit is indicated by a non-significant p value.

Associations between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and continuous variables using the Student's t test.

Binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine predictors of IHMB. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a 95% significance level. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20.0) was used for the statistical analysis.

ResultsPopulation characteristicsThe baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n=2818).

| Demographic data | |

| Age, years | 66±13 |

| Male gender | 73.9 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Hypertension | 67.7 |

| Dyslipidemia | 59.9 |

| Smoking | 31.5 |

| Diabetes | 28.6 |

| Personal history | |

| Heart failure | 5.8 |

| Coronary angioplasty | 17.8 |

| CABG | 5.6 |

| MI | 25.2 |

| Vascular diseasea | 16.3 |

| Bleeding | 3.2 |

| Baseline clinical and laboratory data | |

| Signs of heart failure | 10.9 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 77±18 |

| SBP, mmHg | 139±30 |

| Hematocrit | 41±5 |

| Creatinine clearance, ml/minb | 81±37 |

| Type of ACS | |

| STEMI | 44.4 |

| NSTEMI | 48.4 |

| MI of undetermined location | 3.4 |

| Unstable angina | 3.7 |

| Coronary angiography | 75.3 |

| Radial access | 91.5 |

| Femoral access | 8.5 |

| PCI | 58.3 |

| Antithrombotic therapy | |

| Aspirin | 96.8 |

| Clopidogrel | 73.0 |

| Ticagrelor | 2.8 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 49.0 |

| Fondaparinux | 47.9 |

| Enoxaparin | 16.6 |

| Warfarin | 5.1 |

| IHMB | 1.8 |

| In-hospital mortality | 4.0 |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; GP: glycoprotein; IHMB: in-hospital major bleeding; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP: systolic blood pressure; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as percentage.

A total of 2818 ACS patients were included, 73.9% male, mean age 66±13 years. At admission, mean hematocrit was 41±5%, mean heart rate was 77±18 bpm, mean systolic blood pressure was 139±30 mmHg, mean creatinine clearance was 81±37 ml/min, and 10.9% presented signs of heart failure.

The most frequent diagnosis at admission was NSTEMI (48.4%), followed by STEMI (44.4%). Coronary angiography was performed in 75.3% of patients (91.5% by radial access), and 58.3% underwent PCI.

With regard to antithrombotic therapy during hospitalization, 96.8% of the patients received aspirin, 73% clopidogrel, 2.8% ticagrelor and 47.9% fondaparinux.

During hospital stay, 113 (4.0%) patients died and 52 (1.8%) presented IHMB.

Discriminatory power of the CRUSADE scoreThe rate of IHMB predicted in the study population was 7.1%, while the observed rate was 1.8%, a statistically significant difference (p<0.001) (Table 2).

The incidence of IHMB in the different categories of the CRUSADE score was 0.5% in the very low risk category (rate predicted by the score 3.1%), 1.5% in the low risk category (5.5%), 1.6% in the moderate risk category (8.6%), 5.5% in the high risk category (11.9%), and 4.4% in the high risk category (19.5%) (Table 3).

In-hospital major bleeding observed in the study population and predicted by the CRUSADE score according to CRUSADE risk categories.

| Bleeding risk | n=2615 | Observed IHMB, n (%) | IHMB predicted by the CRUSADE score, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low (1-20) | 931 | 5 (0.5) | 3.1 |

| Low (21-30) | 681 | 10 (1.5) | 5.5 |

| Moderate (31-40) | 509 | 8 (1.6) | 8.6 |

| High (41-50) | 289 | 16 (5.5) | 11.9 |

| Very high (>50) | 205 | 9 (4.4) | 19.5 |

IHMB: in-hospital major bleeding.

The predictive ability of the CRUSADE score in the study population was moderate, with an AUC of 0.73 (Figure 1).

Predictors of in-hospital major bleedingThe occurrence of IHMB was associated with the following variables: advanced age (p=0.01), hypertension (p=0.029), angina (p=0.01), previous bleeding (p<0.001), COPD (p=0.021), cancer (p<0.001), higher baseline heart rate (p<0.001), lower hemoglobin (p=0.005), femoral access (p<0.001), and lower LVEF at discharge (p<0.001). IHMB was also associated with higher in-hospital mortality (15.4% vs. 3.8%; p<0.001) (Table 4).

Variables associated with in-hospital major bleeding.

| No IHMB (n=2766) | IHMB (n=52) | p | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66±13 | 74±11 | 0.01 | 3.65 (2.05-6.92)a |

| Hypertension | 67.4 | 82.0 | 0.029 | 2.31 (1.12-4.76) |

| Angina | 39.0 | 56.9 | 0.01 | 2.13 (1.22-3.72) |

| Previous bleeding | 2.9 | 20.0 | <0.001 | 7.99 (3.87-16.50) |

| COPD | 4.8 | 11.8 | 0.021 | 2.58 (1.08-6.15) |

| Cancer | 4.2 | 15.7 | <0.001 | 4.15 (1.91-9.02) |

| Heart rate, bpm | 76±18 | 88±27 | <0.001 | 4.01 (3.15-8.03)b |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.8±1.8 | 13.1±2.2 | 0.005 | 2.90 (1.06-5.85)c |

| Femoral access | 8.0 | 35.1 | <0.001 | 6.10 (3.39-10.97) |

| LVEF | 57±13 | 49±12 | <0.001 | 5.15 (3.01-8.57)d |

| Enoxaparin | 16.3 | 32.7 | 0.002 | 2.49 (1.38-4.49) |

| Warfarin | 5.0 | 11.5 | 0.034 | 2.48 (1.04-5.92) |

| Ticagrelor | 2.7 | 9.1 | 0.028 | 3.81 (1.48-9.87) |

| Mortality | 3.8 | 15.4 | <0.001 | 4.61 (2.12-10.03) |

CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IHMB: in-hospital major bleeding; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; OR: unadjusted odds ratio. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as percentage.

When the above significant associations were included in multivariate analysis, advanced age (p=0.027), femoral access (p=0.004), higher heart rate (p=0.047) and medication with ticagrelor during hospital stay (p=0.027) were identified as independent predictors of IHMB (Table 5).

DiscussionIn this contemporary population of patients with ACS, the CRUSADE score overestimated the risk of IHMB.

In-hospital major bleedingThe incidence of IHMB in the literature is 1-10%; this variability is due to various factors including differences in patient characteristics, concomitant therapy and definitions of bleeding.3

The rate of IHMB in our study was 1.8%. This is significantly lower than that predicted by the CRUSADE score (7.1%) (p<0.001). The CRUSADE score overestimated bleeding risk in all risk categories, with greater differences in higher risk categories (moderate, high and very high).

These findings may be explained by evidence that the rate of IHMB in patients with ACS has decreased over time, despite the use of more aggressive drug therapies and interventions. Fox et al. reported a significant fall in bleeding rates in patients with ACS between 2000 and 2007, from 2.6% to 1.8% (p<0.001).16 Factors contributing to this decrease include improvements in cardiac catheterization techniques, the introduction of smaller catheters, the use of radial access, better selection of antithrombotic therapy and changes to thresholds for red blood cell transfusion.16

Patients with IHMB have a worse prognosis, with greater risk for in-hospital mortality.16,17 In a study by Spencer et al. of 40087 patients with MI, IHMB was associated with greater mortality (21% vs. 6%, p<0.001).17 IHMB was also associated with higher mortality in our study (15.4% vs. 3.8%, p<0.001). Measures must be taken to reduce the negative impact of IHMB on prognosis in ACS. However, several risk factors for bleeding are also predictors of ischemic events, complicating the task of maximizing anti-ischemic effectiveness while minimizing bleeding risk.7,10

Discriminatory power of the CRUSADE scoreThe ability of the CRUSADE score to predict IHMB in our population was acceptable, with an AUC of 0.73. However, this is hardly an optimal result. In a cohort of 4500 patients with ACS, Abu-Assi et al. assessed the performance of the CRUSADE score, finding a c-statistic of 0.80 for predicting major bleeding events,9 and similarly, Manzano-Fernández et al. calculated an AUC of 0.79 in a study of 1587 patients with ACS.1 However, other studies have reported lower figures: the AUC was 0.70 in a study of 1976 patients with ACS by Ariza-Solé et al.,18 while Amador et al. found an AUC of 0.61 in their population of 516 ACS patients.19 The CRUSADE score has been shown to have poor predictive ability, with AUC values below 0.70, in certain subgroups, including those aged over 75 years, those who have not undergone coronary angiography, and those not receiving anticoagulant therapy.9,20,21 Its performance was actually rather modest (AUC 0.68) in the population in which the score was developed.7

There is thus considerable variability in the discriminatory power of the CRUSADE score in ACS patients. This may be due to a range of factors that hinder assessment of bleeding risk, including age, comorbidities, antithrombotic therapy, choice of strategy (invasive or conservative), and site of vascular access for angiography. There is a need for a score that is suitable for current clinical practice and that can provide accurate, individualized and simple bleeding risk stratification in patients with ACS.

Predictors of in-hospital major bleedingThe independent predictors of IHMB identified in our study were advanced age, higher heart rate on admission, femoral access and medication with ticagrelor during hospital stay.

As pointed out above, patients with ACS are a heterogeneous population, which means that different predictors of major bleeding will be found in different patient populations. A study by Mehran et al. in 17421 patients with ACS identified seven predictors of bleeding, including female gender, advanced age, elevated serum creatinine, white cell count, anemia and use of unfractionated heparin plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor.22 Moscucci et al. determined female gender, advanced age, renal insufficiency and history of bleeding as independent predictors of bleeding among 24045 ACS patients in the GRACE registry.23 As well as age, female gender and renal insufficiency, Nikolsky et al. identified pre-existing anemia, administration of low molecular weight heparin within 48 hours pre-PCI, and use of intra-aortic balloon pump as predictors of major bleeding.24 Although there are differences between these studies in the incidence and definition of bleeding, age, female gender and renal failure are frequently identified variables.2,22,23 In our study, ticagrelor use was a predictor of IHMB, although it should be borne in mind that only 2.8% of our population were taking the drug. In the PLATO trial, compared to clopidogrel, treatment with ticagrelor reduced vascular mortality, MI and stroke, but was associated with a higher rate of bleeding not related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery (4.5% vs. 3.8%; p=0.03).25

Vascular access for coronary angiographyIn our study, 91.5% of patients underwent angiography via radial access, a higher proportion than in other studies assessing the applicability of the CRUSADE score, which reported rates between 64% and 83.1%.1,9,18,26 In multivariate analysis, femoral access was an independent predictor of IHMB (p=0.004), which is in line with recent clinical evidence.27,28 However, when interpreting this result it should be borne in mind that femoral access was used in only 8.5% of patients.

Periprocedural major bleeding is a complication that can affect patients undergoing PCI, with an incidence of 1.7-3.5% in recent studies.29–31 Multiple studies have shown that radial access is associated with lower rates of periprocedural bleeding than femoral access.32–35

The RIVAL trial reported a lower rate of major vascular complications for radial access in patients with ACS (1.4% vs. 3.7%; p<0.0001).35 However, results for mortality were inconsistent, with lower mortality in patients with STEMI but not in those with non-ST-elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS). In the MATRIX trial, radial access reduced bleeding complications and overall mortality in patients with ACS (STEMI and NSTEMI) compared to femoral access.27 In the European guidelines the use of radial access is a class I recommendation, level of evidence A.10

The high rate of radial access in our study may have contributed to the low rate of IHMB in our population. The fact that access type is not included in its parameters constitutes a limitation of the CRUSADE score.

FondaparinuxRegarding anticoagulation, fondaparinux was used in 47.9% of our population, considerably more than enoxaparin (16.6%).

In the OASIS-5 trial in patients with NSTE-ACS, fondaparinux significantly reduced major bleeding events compared to enoxaparin (p<0.001).36 Fondaparinux is the parenteral anticoagulant recommended in the current guidelines for NSTE-ACS patients, due to its safety and efficacy profile.10 Despite this recommendation, rates of fondaparinux use in other series are lower than in ours (1.6-14%).1,9,37

We believe that the use of this anticoagulant in our population may also have contributed to the low rate of IHMB.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and P2Y12 receptor inhibitorsGP IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used in 49% of our population, a higher rate than in other series (5.7-40.2%).1,9,18,19,37 It should, however, be noted that in most cases this consisted only of the administration of a bolus of eptifibatide during coronary angiography and that the drug was not infused after angioplasty, which may have contributed to our low rate of periprocedural bleeding complications.

There is evidence that in patients with NSTE-ACS undergoing PCI, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors reduce ischemic events, mainly reinfarction, although they also increase bleeding.6,38

Following the HORIZONS-AMI trial, which showed that anticoagulation with bivalirudin alone was superior to heparin plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients undergoing primary PCI, with significantly reduced 30-day rates of major bleeding and mortality,39 use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors declined. The current European guidelines recommend GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors only for bailout or in cases of thrombotic complications (class IIa recommendation, level of evidence C).10,40

By contrast, the US guidelines6 state that in patients with NSTE-ACS and high-risk features not adequately pretreated with clopidogrel or ticagrelor, it is useful to administer a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (class I recommendation, level of evidence A), and in NSTE-ACS patients treated with unfractionated heparin and adequately pretreated with clopidogrel, it is reasonable to administer a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (class IIa recommendation, level of evidence B).

It should be noted that our patients preferably received a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor during or after angioplasty, which may also have contributed to the low rate of major bleeding. Current guidelines recommend pretreatment with a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor for patients with ACS.6,10,40 However, questions have been raised41,42 concerning pretreatment in NSTE-ACS, such as by the ACCOAST trial,42 which demonstrated that pretreatment with prasugrel did not reduce the rate of ischemic events, but did increase the rate of major bleeding.

Clinical implicationsAntithrombotic therapy, which is an essential part of anti-ischemic therapy in ACS, also increases bleeding risk. Patients with ACS are a highly heterogeneous population and stratification of both ischemic and bleeding risk is needed in order to institute appropriate therapy with the desired efficacy while minimizing undesired effects.31 However, in the last ten years there have been significant changes in the management and treatment of ACS patients that may have altered the predictive value of risk scores.10 There is thus a need to develop tools to stratify bleeding risk that aim to promote strategies that reduce bleeding rates and thereby improve prognosis in these patients.9

LimitationsThis was a single-center, retrospective, observational study, and was thus subject to the inherent biases of such studies. The low rate of bleeding events may have influenced the results, which should be validated in a larger patient cohort.

The use of different definitions of major bleeding is another limitation of our study. In the CRUSADE trial, major bleeding was defined as intracranial hemorrhage, documented retroperitoneal bleed, hematocrit drop ≥12% (baseline to nadir), any red blood cell transfusion when baseline hematocrit ≥28%, or any red blood cell transfusion when baseline hematocrit <28% with witnessed bleed. In our study the GUSTO classification was used, which defines major bleeding as intracerebral bleeding or bleeding resulting in hemodynamic compromise requiring treatment.13

ConclusionsThe IHMB rate in our study was 1.8%. The CRUSADE score, although presenting some discriminatory power, significantly overestimated the IHMB rate, especially in patients at higher risk. These results question whether the CRUSADE score should continue to be used in the stratification of bleeding risk in ACS and whether specific measures should be taken on the basis of the score result.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bento D, Marques N, Azevedo P, et al. Score CRUSADE – Será ainda um bom score para prever a hemorragia na síndrome coronária aguda? Rev Port Cardiol. 2018;37:889–897.