Due to the chronic inflammation associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), patients develop premature atherosclerosis and the disease is a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction. The best interventional treatment for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in these patients is unclear. The objective of this study is to describe the baseline characteristics, clinical manifestations, treatment and in-hospital outcome of patients with SLE and ACS.

MethodsEleven SLE patients with ACS were analyzed retrospectively between 2004 and 2011. The following data were obtained: age, gender, clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics, Killip class, risk factors for ACS, myocardial necrosis markers (CK-MB and troponin), creatinine clearance, left ventricular ejection fraction, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), drugs used during hospital stay, treatment (medical, percutaneous or surgical) and in-hospital outcome. The statistical analysis is presented in percentages and absolute values.

ResultsTen of the patients (91%) were women. The median age was 47 years. Typical precordial pain was present in 91%. Around 73% had positive erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The vessel most often affected was the anterior descending artery, in 73%. One patient underwent coronary artery bypass grafting, seven underwent percutaneous coronary intervention with bare-metal stents and three were treated medically. In-hospital mortality was 18%.

ConclusionsDespite the small number of patients, our findings were similar to those in the literature, showing coronary artery disease in young people with SLE due to premature atherosclerosis and a high mortality rate.

Devido ao caráter inflamatório crônico do lupus eritematoso sistêmico (LES), os pacientes apresentam reconhecidamente o desenvolvimento de aterosclerose precoce, sendo a própria doença um fator de risco independente para a ocorrência de infarto agudo do miocárdio. Em síndromes coronárias agudas (SCA) a melhor forma de tratamento intervencionista mantém-se indefinido. Dessa forma, descrevemos as características basais, manifestações clínicas, achados angiográficos, tratamento definitivo adotado e a evolução intra-hospitalar de pacientes com LES que apresentaram SCA.

MétodosEntre 2004-2011 foram analisados retrospectivamente 11 pacientes com LES que apresentaram SCA. As seguintes informações foram obtidas: idade, sexo, manifestações clínicas e eletrocardiográficas, estado hemodinâmico, fatores de risco para SCA, marcadores de necrose miocárdica, clearance de creatinina, fração de ejeção de ventrículo esquerdo, marcadores inflamatórios, autoanticorpos, medicações utilizadas, achados angiográficos, tratamento definitivo adotado e evolução intra-hospitalar.

ResultadosDez (91%) pacientes eram mulheres. A mediana de idade foi 47 anos. Dor precordial típica esteve presente em 91%. Cerca de 73% apresentaram aumento de velocidade de hemossedimentação. O seguimento mais acometido foi a artéria descendente anterior em 73%. Em um caso optou-se por revascularização cirúrgica, em sete pacientes realizou-se angioplastia com stent convencional e em três doentes manteve-se tratamento clínico. Obteve-se mortalidade intra-hospitalar de 18%.

ConclusãoApesar da casuística limitada, os dados encontrados são semelhantes ao restante da literatura, ressaltando a precocidade da doença coronária, a presença de aterosclerose como desencadeante principal e a amplitude de sua gravidade com elevada taxa de mortalidade intra-hospitalar.

acute coronary syndrome

coronary artery bypass grafting

coronary artery disease

creatinine clearance

myocardial infarction

percutaneous coronary intervention

systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an uncommon autoimmune disease of unknown cause, with an estimated prevalence of 1/2000 and a male:female ratio of 1:10. Cardiovascular involvement is one of the most common and serious manifestations of the disease, in the form of myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis, vasculitis or coronary artery disease (CAD).1

Due to the chronic inflammation associated with SLE, patients develop premature atherosclerosis, and the disease is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction (MI).1–3 The therapeutic approach can be a challenge and the best interventional treatment for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in these patients is unclear. Some case series have reported their experience with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and/or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), but they show conflicting results.3,4

The objective of this study is to describe the baseline characteristics, clinical manifestations, treatment and in-hospital outcome of patients with SLE and ACS.

MethodsEleven SLE patients who presented ACS (unstable angina and/or MI) were analyzed retrospectively between 2004 and 2011. The diagnosis of SLE was based on the 1997 revised criteria of the American College of Rheumatology.5

All patients with typical chest pain were immediately diagnosed with ACS and were risk stratified according to the clinical presentation. Those with atypical pain and/or ischemic equivalent symptoms, such as dyspnea, were treated according to the chest pain protocol, being kept under observation for 12 hours with monitoring of ECG and markers of myocardial necrosis (troponin and CK-MB) every three hours. In cases of ECG alterations (ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion) and/or positive necrosis markers, a diagnosis of ACS was made and they were included in the study.

The following data were recorded: age, gender, clinical and ECG manifestations, Killip class, risk factors for ACS, markers of myocardial necrosis (CK-MB and troponin), creatinine clearance (CrCl), left ventricular ejection fraction, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), autoantibodies, medication during hospital stay, angiographic findings, treatment (medical, PCI and/or CABG) and in-hospital outcome.

Coronary lesions were considered significant with ≥70% stenosis.

The type of stent (bare-metal or drug-eluting) employed in PCI procedures was recorded, as well as arterial and/or venous grafts in CABG.

The statistical analysis is presented in percentages and absolute values.

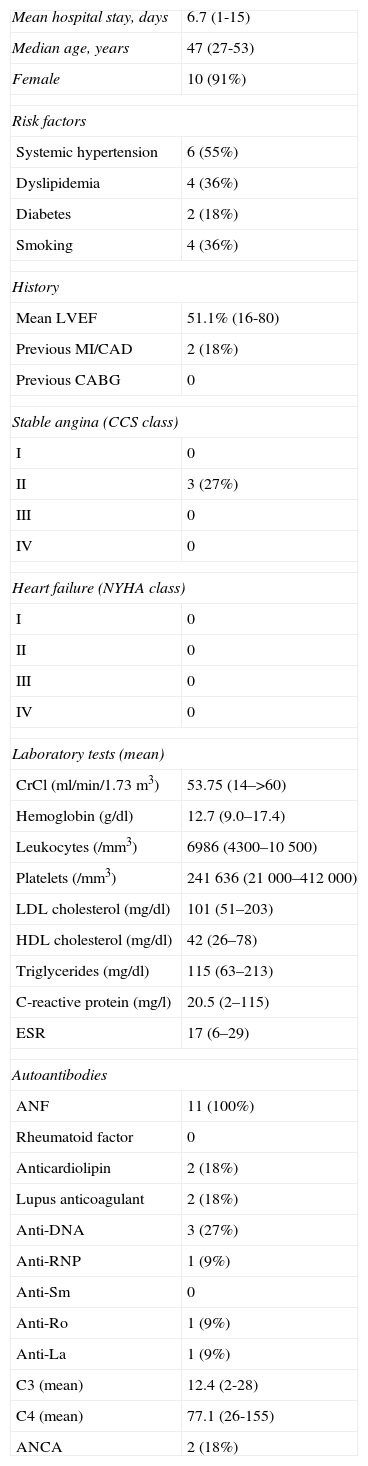

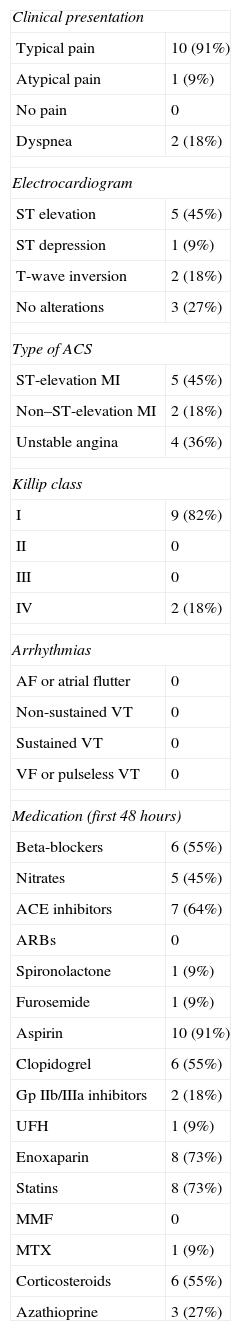

ResultsTen patients were women (91%). The median age was 47 years. The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The most common clinical presentation was MI (64% of cases), with ST elevation in 45%, as shown in Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Mean hospital stay, days | 6.7 (1-15) |

| Median age, years | 47 (27-53) |

| Female | 10 (91%) |

| Risk factors | |

| Systemic hypertension | 6 (55%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 (36%) |

| Diabetes | 2 (18%) |

| Smoking | 4 (36%) |

| History | |

| Mean LVEF | 51.1% (16-80) |

| Previous MI/CAD | 2 (18%) |

| Previous CABG | 0 |

| Stable angina (CCS class) | |

| I | 0 |

| II | 3 (27%) |

| III | 0 |

| IV | 0 |

| Heart failure (NYHA class) | |

| I | 0 |

| II | 0 |

| III | 0 |

| IV | 0 |

| Laboratory tests (mean) | |

| CrCl (ml/min/1.73m3) | 53.75 (14–>60) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.7 (9.0–17.4) |

| Leukocytes (/mm3) | 6986 (4300–10500) |

| Platelets (/mm3) | 241636 (21000–412000) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 101 (51–203) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 42 (26–78) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 115 (63–213) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 20.5 (2–115) |

| ESR | 17 (6–29) |

| Autoantibodies | |

| ANF | 11 (100%) |

| Rheumatoid factor | 0 |

| Anticardiolipin | 2 (18%) |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 2 (18%) |

| Anti-DNA | 3 (27%) |

| Anti-RNP | 1 (9%) |

| Anti-Sm | 0 |

| Anti-Ro | 1 (9%) |

| Anti-La | 1 (9%) |

| C3 (mean) | 12.4 (2-28) |

| C4 (mean) | 77.1 (26-155) |

| ANCA | 2 (18%) |

ANF: antinuclear factor; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CrCl: creatinine clearance; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of the study population.

| Clinical presentation | |

| Typical pain | 10 (91%) |

| Atypical pain | 1 (9%) |

| No pain | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 2 (18%) |

| Electrocardiogram | |

| ST elevation | 5 (45%) |

| ST depression | 1 (9%) |

| T-wave inversion | 2 (18%) |

| No alterations | 3 (27%) |

| Type of ACS | |

| ST-elevation MI | 5 (45%) |

| Non–ST-elevation MI | 2 (18%) |

| Unstable angina | 4 (36%) |

| Killip class | |

| I | 9 (82%) |

| II | 0 |

| III | 0 |

| IV | 2 (18%) |

| Arrhythmias | |

| AF or atrial flutter | 0 |

| Non-sustained VT | 0 |

| Sustained VT | 0 |

| VF or pulseless VT | 0 |

| Medication (first 48 hours) | |

| Beta-blockers | 6 (55%) |

| Nitrates | 5 (45%) |

| ACE inhibitors | 7 (64%) |

| ARBs | 0 |

| Spironolactone | 1 (9%) |

| Furosemide | 1 (9%) |

| Aspirin | 10 (91%) |

| Clopidogrel | 6 (55%) |

| Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 2 (18%) |

| UFH | 1 (9%) |

| Enoxaparin | 8 (73%) |

| Statins | 8 (73%) |

| MMF | 0 |

| MTX | 1 (9%) |

| Corticosteroids | 6 (55%) |

| Azathioprine | 3 (27%) |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AF: atrial fibrillation; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; Gp: glycoprotein; MI: myocardial infarction; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; MTX: methotrexate; UFH: unfractionated heparin; VF: ventricular fibrillation; VT: ventricular tachycardia.

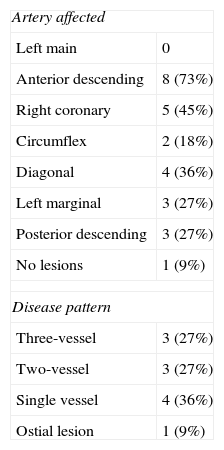

The arterial segments most commonly affected were the anterior descending artery (in 73%) and the right coronary artery (in 45%), followed by the diagonal artery (in 36%). Only in one case (9%) was no obstructive coronary lesion detected. One patient (9%) had an ostial lesion, three (27%) had three-vessel disease and three (27%) had two-vessel disease (Table 3).

Angiographic features of the study population.

| Artery affected | |

| Left main | 0 |

| Anterior descending | 8 (73%) |

| Right coronary | 5 (45%) |

| Circumflex | 2 (18%) |

| Diagonal | 4 (36%) |

| Left marginal | 3 (27%) |

| Posterior descending | 3 (27%) |

| No lesions | 1 (9%) |

| Disease pattern | |

| Three-vessel | 3 (27%) |

| Two-vessel | 3 (27%) |

| Single vessel | 4 (36%) |

| Ostial lesion | 1 (9%) |

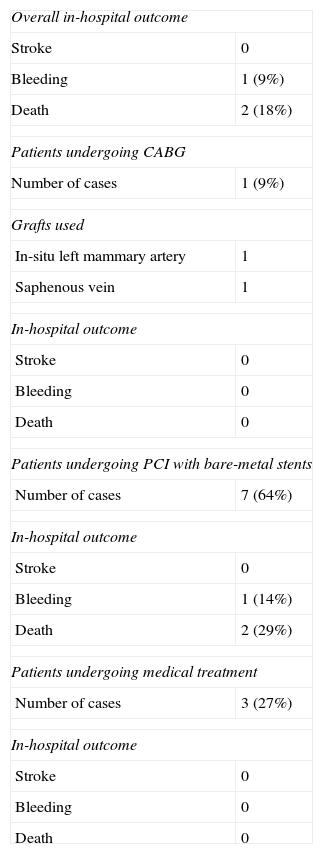

CABG was performed in one patient, PCI with bare-metal stents in seven, and medical treatment was maintained in three. In-hospital mortality was 18% (Table 4)

Treatment and in-hospital outcome of the study population.

| Overall in-hospital outcome | |

| Stroke | 0 |

| Bleeding | 1 (9%) |

| Death | 2 (18%) |

| Patients undergoing CABG | |

| Number of cases | 1 (9%) |

| Grafts used | |

| In-situ left mammary artery | 1 |

| Saphenous vein | 1 |

| In-hospital outcome | |

| Stroke | 0 |

| Bleeding | 0 |

| Death | 0 |

| Patients undergoing PCI with bare-metal stents | |

| Number of cases | 7 (64%) |

| In-hospital outcome | |

| Stroke | 0 |

| Bleeding | 1 (14%) |

| Death | 2 (29%) |

| Patients undergoing medical treatment | |

| Number of cases | 3 (27%) |

| In-hospital outcome | |

| Stroke | 0 |

| Bleeding | 0 |

| Death | 0 |

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Cardiac involvement in SLE is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in these patients. The first reports of this association appeared in the 1960s.1,6 The incidence of MI in young SLE patients due to premature atherosclerosis is 9–50 times higher than in age-matched controls, making SLE an independent risk factor for CAD.1–3,7 The risk is even higher in young women, due to the lack of awareness among the medical community of the association, resulting in the diagnosis being overlooked even in the presence of typical symptoms in patients considered at low cardiovascular risk.1,7

A study by Hak et al.8 assessed the incidence of cardiovascular events in a retrospective cohort of 148 women with SLE over a period of 28 years. Of this group, 13.5% suffered a cardiovascular event during follow-up, at a mean age of 53 years. The incidence of MI was around three times higher than for those without SLE, with a relative risk of 2.25 (95% confidence interval: 1.37–3.69).8 There was a predominance of women in our series (91%), and median age was 47 years, in agreement with the literature. The youngest patient in our population, a 27-year-old woman, was one of those who died during hospitalization, which highlights the need for prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Among SLE patients aged under 35, MI is the most common manifestation of cardiovascular disease, followed by heart failure, sudden death and angina.1,7 In autopsy studies, 54% of patients have significant atherosclerosis. There is limited use of ischemia testing to diagnose CAD in SLE patients due to their age and the predominance of women.3,4 Nevertheless, when asymptomatic patients with SLE undergo myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, 35–40% have perfusion deficits.1,3 Computed tomography coronary angiography studies have shown a higher incidence of noncalcified plaques in SLE patients than in controls.9 Furthermore, coronary flow reserve is also reduced in these patients even in the absence of significant coronary lesions, reflecting the presence of chronic inflammation.2 With regard to the clinical presentation of CAD, our findings were similar to those in the literature. MI was the type of ACS in 64% of patients, with 45% of the total presenting ST elevation and 91% reporting typical chest pain.

The pathophysiology of coronary involvement in SLE remains unclear. Besides conventional risk factors, the principal cause is thought to be premature atherosclerosis resulting from chronic inflammation and endothelial damage associated with the disease, together with chronic use of drugs such as corticosteroids.3,10 However, SLE patients can also suffer ACS due to their higher risk of vascular thrombosis, especially when SLE is associated with antiphospholipid syndrome (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies increases the risk of MI and sudden death four-fold).1–3,10–12 Traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis should be thoroughly investigated and aggressively treated in SLE patients. Systemic hypertension is found in up to 75%, and greatly increases their risk of cardiovascular events. In addition, smoking increases the risk of MI three-fold, as well as reportedly reducing the effect of antimalarial drugs. Lastly, the lipid profile of SLE patients is altered in 40% of cases, with high levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides, although unexpectedly, there is no correlation between SLE and diabetes, the association being found in only 1.9% of patients.1,10 By contrast, 18% of our patients had been diagnosed with diabetes, but the findings of our study are in agreement with the literature in terms of the prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidemia, 55% and 36% respectively.

With regard to inflammation, high serum levels of pro-atherogenic cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-17 have been found in SLE patients with ACS. Hyperhomocysteinemia, oxidized low-density lipoprotein and insulin resistance have also been reported in this patient group. Furthermore, SLE activity appears to be directly related to risk of MI, especially in patients with renal involvement, reduced CrCl and positive anti-DNA autoantibodies.1,2,4,10,13,14

Some studies have shown that chronic corticosteroid use is an independent determinant of premature atherosclerosis, as well as increasing body weight and blood pressure and altering serum levels of circulating cholesterol.1,10,15

In our study population, which included only SLE patients with ACS, angiography showed diffuse atherosclerosis in all cases, irrespective of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, with significant multivessel CAD in 54%, but no cases of coronary thrombosis. This corroborates previous findings that premature atherosclerosis is the main cause of MI in patients with SLE. A study by Lee et al.7 of 25 cases of SLE with CAD found that 20% of patients had more than one significant coronary lesion and also reported no cases of thrombosis. However, certain characteristics reported in other studies were not observed in our study population: only 27% had positive anti-DNA autoantibodies, CrCl was generally preserved, and the inflammatory markers C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were elevated in only 45% and 73%, respectively. Furthermore, C4 was reduced in only 27% of cases, while C3 was reduced in 73%.

In-hospital mortality was 18% in the present study, around three times higher than mortality due to ACS in the general population. Moreover, the prevalence of ST-elevation MI was also higher, practically double the rate found in patients without SLE. These findings are in agreement with those of Roldan,4 who reported short- and long-term mortality at least twice as high in patients with ACS and SLE than in the general population. However, a long-term follow-up study of PCI in SLE patients reported zero mortality, highlighting the need for further studies to assess the specific characteristics of coronary treatment in these patients.7 The best interventional treatment is unclear. Reported rates of adverse events (thrombosis or restenosis) following bare-metal and drug-eluting coronary stenting in SLE patients are 35% and 14%, respectively.4,7 Studies of SLE patients undergoing CABG have shown good outcomes and safety, albeit only in small series.3,4,16,17

ConclusionsPatients with SLE have a higher risk of MI compared to those without the disease. Despite the small number of patients, our findings were similar to those in the literature, showing CAD in young people with SLE due to premature atherosclerosis and a high mortality rate.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de Matos Soeiro A, de Almeida Soeiro MCF, de Oliveira Jr MT, Serrano Jr CV. Características clínicas, angiográficas e evolução intra-hospitalar em pacientes com lúpus eritematoso sistêmico e síndrome coronária aguda. Rev Port Cardiol. 2014;33:685–690.