In recent years, cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs have evolved from being limited to exercise training to comprehensive secondary prevention programs. Given the solid scientific evidence supporting them, they are given a class I recommendation in the American and European guidelines for various cardiovascular diseases, but they continue to be underused in Portugal.

ObjectiveTo analyze the situation of CR programs in Portugal in 2013-14 and to assess developments in recent years.

MethodsIn November 2014, a questionnaire was sent to the centers offering CR programs that included the following items: name of the center; composition of the team; phases and components; number of participants and diagnoses; and funding bodies. The percentage of patients with myocardial infarction admitted to phase II CR programs in 2013 was calculated based on data from the Directorate-General of Health (DGS).

ResultsTwenty-three centers offering CR programs were identified, 12 public and 11 private. The number of centers rose from 16 in 2007 to 23 in 2014. In 2013, 1927 patients participated in phase II programs, nearly three times the number rehabilitated in 2007 (638 patients). Myocardial infarction was the referral diagnosis in 999 patients, accounting for 51.8% of admissions. On the basis of DGS data, 8% of patients with myocardial infarction were admitted to phase II CRPs in 2013, as opposed to 3% in 2007.

ConclusionThe number of patients admitted to CR programs, as well as the number of centers, increased considerably between 2007 and 2014 in Portugal. Despite these favorable developments, further improvements are still needed.

Nos últimos anos os programas de reabilitação cardíaca (PRC) evoluíram, deixaram de se basear apenas no exercício físico e são atualmente programas abrangentes de prevenção secundária. Dada a evidência científica sólida que os suporta, mereceram recomendação classe I para várias patologias cardiovasculares, nas recomendações americanas e europeias. Continuam, no entanto, a ser subutilizados em Portugal.

ObjetivosConhecer os PRC nacionais em 2013-14 e analisar a sua evolução.

Material e métodosEm novembro de 2014 foi enviado aos centros um questionário com os seguintes itens: identificação do centro; constituição da equipa; fases e componentes; número de participantes, respetivas patologias e entidades pagadoras. Considerando os dados da Direção Geral de Saúde (DGS), calculou-se a percentagem de doentes com alta após enfarte admitidos em PRC, fase 2, em 2013.

ResultadosIdentificaram-se 23 centros com PRC, 12 públicos e 11 privados. O número de centros evoluiu de 16 em 2007 para 23 em 2014. Em 2013 participaram em PRC, fase 2, 1927 doentes, o triplo dos 638 reabilitados em 2007. O enfarte foi o diagnóstico de admissão de 999 doentes, representando 51,8% das admissões. Considerando os dados da DGS, constata-se que 8% dos doentes com alta após enfarte frequentaram PRC, fase 2, em 2013. Em 2007 esse valor era de 3%.

ConclusãoO volume de doentes em PRC e o número de centros aumentou consideravelmente em Portugal entre 2007-2014. Apesar da evolução favorável é necessário continuar a desenvolver estratégias de divulgação e implementação de PRC no nosso país.

Mortality from coronary artery disease (CAD) has decreased in recent decades in developed countries, but morbidity associated with CAD has increased. Improvements in diagnostic techniques and treatment in the acute phase of myocardial infarction (MI) have improved survival in these patients,1,2 which makes it particularly important to develop strategies for secondary prevention.

At the same time, cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs have evolved from being limited to exercise training to comprehensive secondary prevention programs. They now include certain essential components: patient assessment, therapeutic optimization, diet/nutritional counseling, risk factor management, psychosocial management and vocational advice, physical activity counseling and exercise training.3,4 Such comprehensive CR programs aim not only to improve functional capacity but also to foster healthy behaviors and compliance with therapy, with a view to delaying progression of atherosclerotic disease and preventing future cardiac events.

Various studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated the benefits of CR, particularly in CAD patients, in whom they have reduced overall mortality by 20%, cardiac mortality by 26%, and rehospitalization by 25%.5–7 Based on this evidence, CR is a class I recommendation for CAD in both the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation and the European Society of Cardiology guidelines.8–12 In recent years, this recommendation has been extended to heart failure (HF) patients.13

Despite the well-documented benefits of CR, it continues to be underused and few programs have been implemented in Portugal. The Portuguese Society of Cardiology's Working Group on Exercise Physiology and Cardiac Rehabilitation has periodically performed national surveys assessing CR in Portugal, first in 1998, and again in 2004 and 2007.14–16 The survey reported here continues this work, assessing the situation regarding CR in Portugal in 2013-14 and analyzing how it has developed by comparing the results with previous surveys.

MethodsIn November 2014, a questionnaire including the following items was sent to all centers offering CR programs:

- -

General information on the center (name, location, public or private, year of beginning CR programs)

- -

Composition of team and coordinators

- -

Description of CRP phases offered

- -

Program components

- -

Total number of participants and distribution by diagnosis in 2013

- -

Funding bodies.

The responses were analyzed and compared with the results of previous surveys. Based on Directorate-General of Health (DGS) data for hospital morbidity17 and the total number of patients with MI admitted for CR by each center, the percentage of patients admitted for a phase II CR program following discharge after MI in 2013 was calculated.

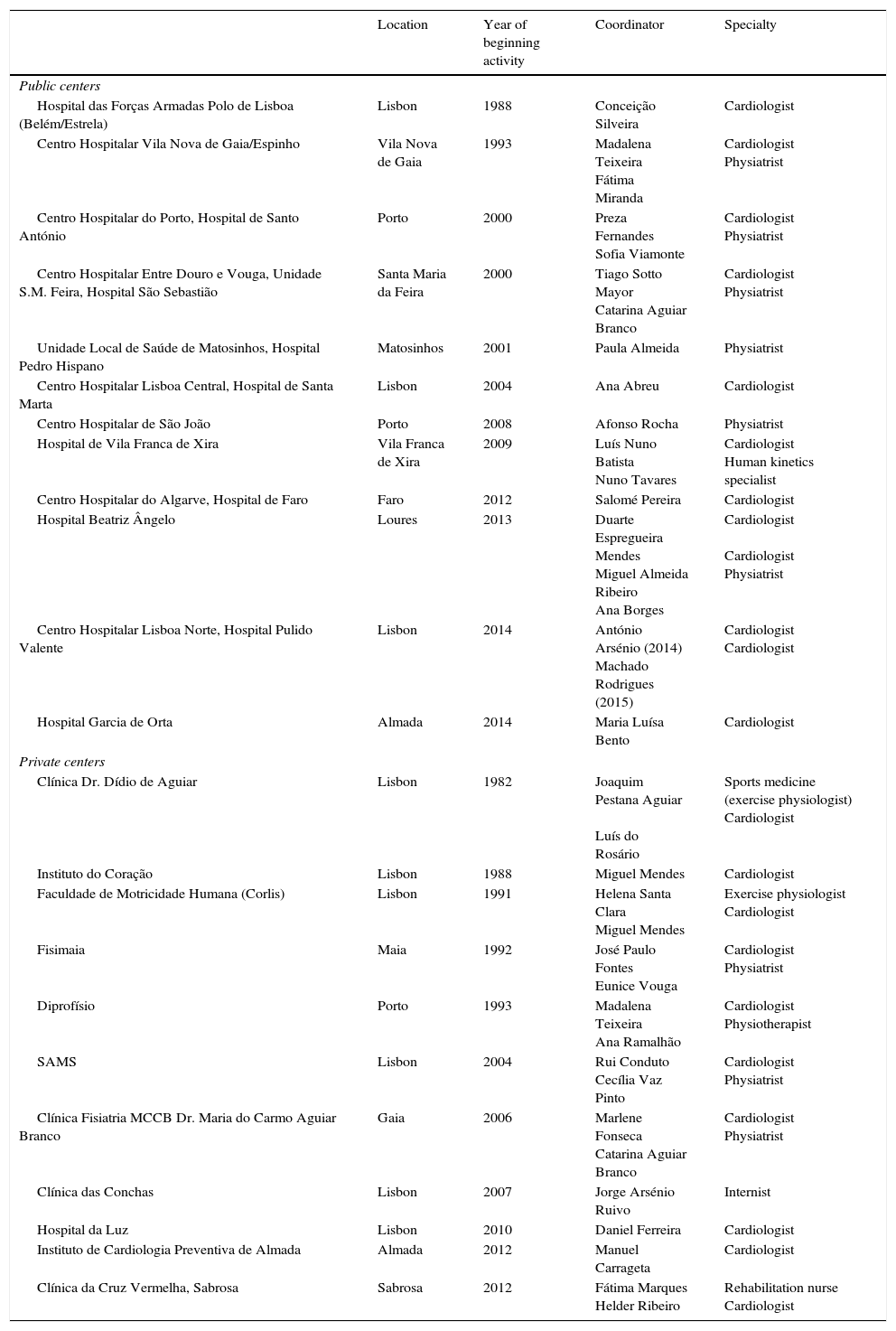

ResultsCardiac rehabilitation centersTwenty-three centers offered CR programs in 2014, 12 public and 11 private (Table 1). There were nine new centers compared to 2007, six public (Hospital de São João, Hospital de Vila Franca de Xira, Hospital de Faro, Hospital Beatriz Ângelo, Hospital Pulido Valente and Hospital Garcia de Orta) and three private (Hospital da Luz, Instituto de Cardiologia Preventiva de Almada and Clínica da Cruz Vermelha, Sabrosa), while three centers (one public and two private) had discontinued CR programs. Following the merger of military hospitals, the CR program of the Belém Military Hospital was moved to the Estrela Military Hospital at the end of 2010 and continued operating there until 2013, and was then transferred to the Hospital das Forças Armadas, Lumiar, in 2014.

Cardiac rehabilitation centers in Portugal in 2014.

| Location | Year of beginning activity | Coordinator | Specialty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public centers | ||||

| Hospital das Forças Armadas Polo de Lisboa (Belém/Estrela) | Lisbon | 1988 | Conceição Silveira | Cardiologist |

| Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho | Vila Nova de Gaia | 1993 | Madalena Teixeira Fátima Miranda | Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Hospital de Santo António | Porto | 2000 | Preza Fernandes Sofia Viamonte | Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Centro Hospitalar Entre Douro e Vouga, Unidade S.M. Feira, Hospital São Sebastião | Santa Maria da Feira | 2000 | Tiago Sotto Mayor Catarina Aguiar Branco | Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos, Hospital Pedro Hispano | Matosinhos | 2001 | Paula Almeida | Physiatrist |

| Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Hospital de Santa Marta | Lisbon | 2004 | Ana Abreu | Cardiologist |

| Centro Hospitalar de São João | Porto | 2008 | Afonso Rocha | Physiatrist |

| Hospital de Vila Franca de Xira | Vila Franca de Xira | 2009 | Luís Nuno Batista Nuno Tavares | Cardiologist Human kinetics specialist |

| Centro Hospitalar do Algarve, Hospital de Faro | Faro | 2012 | Salomé Pereira | Cardiologist |

| Hospital Beatriz Ângelo | Loures | 2013 | Duarte Espregueira Mendes Miguel Almeida Ribeiro Ana Borges | Cardiologist Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte, Hospital Pulido Valente | Lisbon | 2014 | António Arsénio (2014) Machado Rodrigues (2015) | Cardiologist Cardiologist |

| Hospital Garcia de Orta | Almada | 2014 | Maria Luísa Bento | Cardiologist |

| Private centers | ||||

| Clínica Dr. Dídio de Aguiar | Lisbon | 1982 | Joaquim Pestana Aguiar Luís do Rosário | Sports medicine (exercise physiologist) Cardiologist |

| Instituto do Coração | Lisbon | 1988 | Miguel Mendes | Cardiologist |

| Faculdade de Motricidade Humana (Corlis) | Lisbon | 1991 | Helena Santa Clara Miguel Mendes | Exercise physiologist Cardiologist |

| Fisimaia | Maia | 1992 | José Paulo Fontes Eunice Vouga | Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Diprofísio | Porto | 1993 | Madalena Teixeira Ana Ramalhão | Cardiologist Physiotherapist |

| SAMS | Lisbon | 2004 | Rui Conduto Cecília Vaz Pinto | Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Clínica Fisiatria MCCB Dr. Maria do Carmo Aguiar Branco | Gaia | 2006 | Marlene Fonseca Catarina Aguiar Branco | Cardiologist Physiatrist |

| Clínica das Conchas | Lisbon | 2007 | Jorge Arsénio Ruivo | Internist |

| Hospital da Luz | Lisbon | 2010 | Daniel Ferreira | Cardiologist |

| Instituto de Cardiologia Preventiva de Almada | Almada | 2012 | Manuel Carrageta | Cardiologist |

| Clínica da Cruz Vermelha, Sabrosa | Sabrosa | 2012 | Fátima Marques Helder Ribeiro | Rehabilitation nurse Cardiologist |

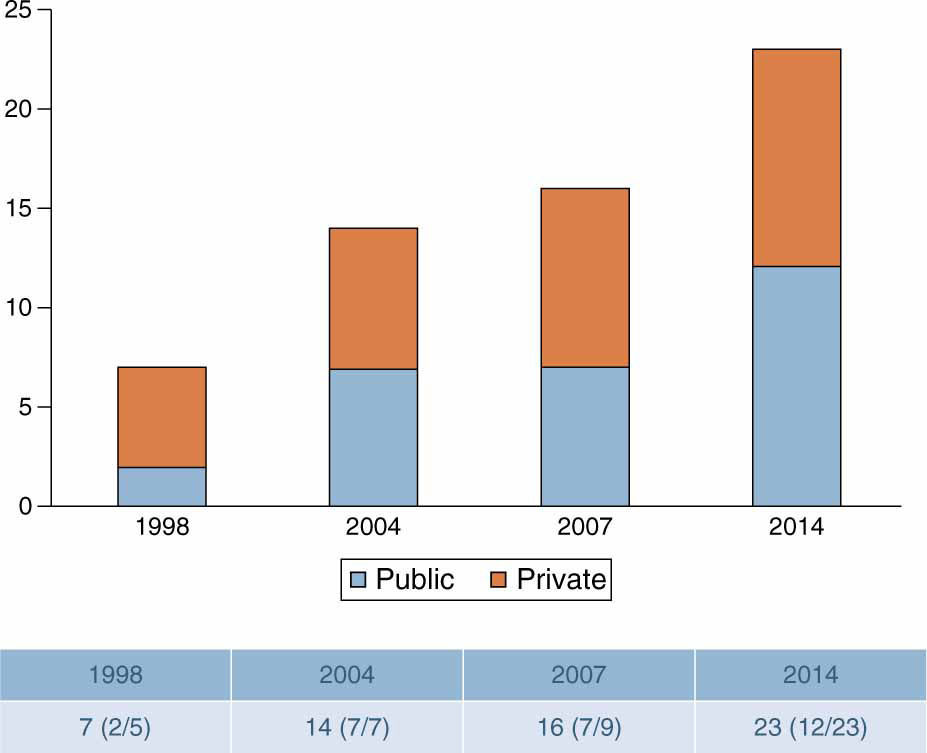

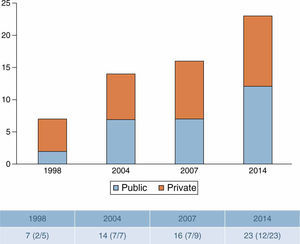

The number of public centers has therefore significantly increased, from only two in 1998 to seven in 2004 and 2007 and 12 in 2014 (Figure 1), but considerable asymmetry persists in the geographical distribution of CR centers, with nine located in the North region, 13 in Greater Lisbon and one in the South region. There are still no CR centers in inland areas (the Central region and the Alentejo) (Figure 2).

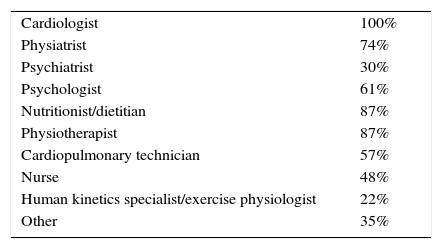

Team composition and coordinatorsAs found in previous surveys, all centers have multidisciplinary teams, and all include a cardiologist. There is also a physiatrist in 74% of centers, a physiotherapist in 87%, an exercise physiologist in 22%, a nutritionist/dietitian in 87%, a psychologist in 61%, a psychiatrist in 30%, a cardiopulmonary technician in 57% and a nurse in 48%. Eight centers have various other health professionals, including internists, pneumologists, vascular surgeons, endocrinologists and social workers (Table 2).

The program is coordinated by a cardiologist in eight centers (35%), a physiatrist in two (9%), jointly by a cardiologist and a physiatrist in seven (30%), a cardiologist and an exercise physiologist in three (13%), a cardiologist and a physiotherapist in one (4%), a cardiologist and a cardiac rehabilitation nurse in one (4%), and an internist in one (4%) (Table 1).

Program phases and componentsPhasesIn 2013 eight centers offered phase I programs (hospital phase), 19 offered phase II (early outpatient phase) and 13 offered phase III (long-term maintenance phase), of varying duration. Only centers offering phase III exercise training were included in the analysis, but some other centers continue to provide clinical assessments, consultations, complementary exams and guidance on level of physical activity at six and 12 months. Two new centers began offering CR in 2014: Hospital Pulido Valente in Lisbon and Hospital Garcia de Orta in Almada. Both offer phase II programs and the latter also has a phase I program.

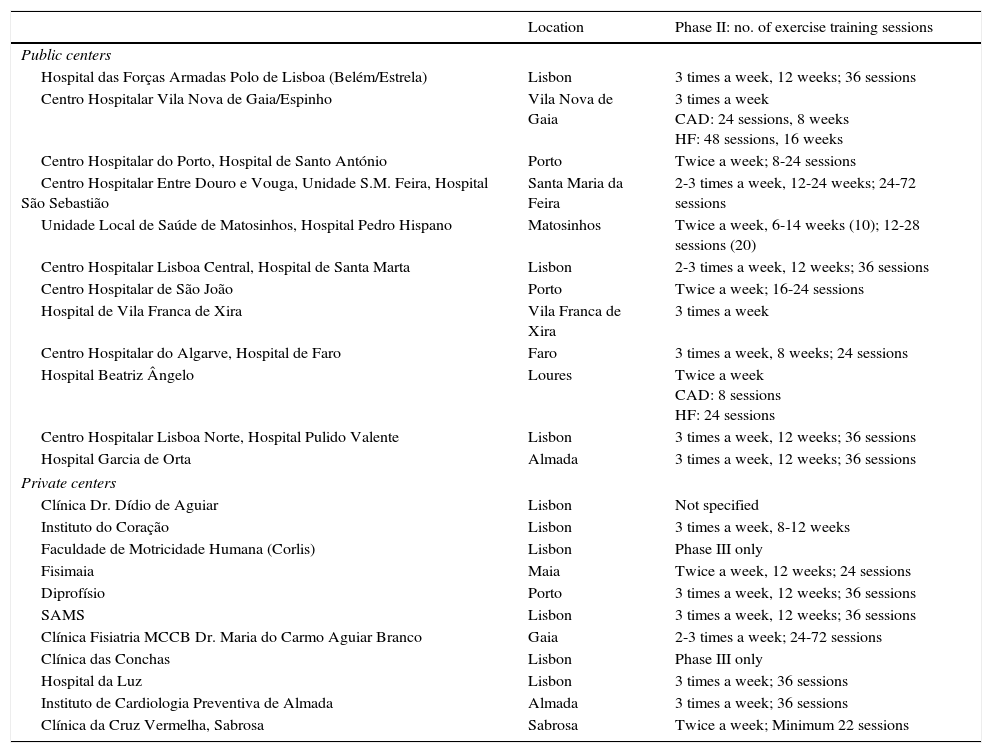

ComponentsExercise training is offered in all centers but is of varying duration. In most centers, phase II programs include 24-36 sessions, two or three times a week over 8-12 weeks. Only two centers, with large numbers of participants, offer shorter programs of eight sessions only. Programs for HF patients are usually longer (Table 3).

Duration of phase II programs and total number of exercise training sessions.

| Location | Phase II: no. of exercise training sessions | |

|---|---|---|

| Public centers | ||

| Hospital das Forças Armadas Polo de Lisboa (Belém/Estrela) | Lisbon | 3 times a week, 12 weeks; 36 sessions |

| Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho | Vila Nova de Gaia | 3 times a week CAD: 24 sessions, 8 weeks HF: 48 sessions, 16 weeks |

| Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Hospital de Santo António | Porto | Twice a week; 8-24 sessions |

| Centro Hospitalar Entre Douro e Vouga, Unidade S.M. Feira, Hospital São Sebastião | Santa Maria da Feira | 2-3 times a week, 12-24 weeks; 24-72 sessions |

| Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos, Hospital Pedro Hispano | Matosinhos | Twice a week, 6-14 weeks (10); 12-28 sessions (20) |

| Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Hospital de Santa Marta | Lisbon | 2-3 times a week, 12 weeks; 36 sessions |

| Centro Hospitalar de São João | Porto | Twice a week; 16-24 sessions |

| Hospital de Vila Franca de Xira | Vila Franca de Xira | 3 times a week |

| Centro Hospitalar do Algarve, Hospital de Faro | Faro | 3 times a week, 8 weeks; 24 sessions |

| Hospital Beatriz Ângelo | Loures | Twice a week CAD: 8 sessions HF: 24 sessions |

| Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte, Hospital Pulido Valente | Lisbon | 3 times a week, 12 weeks; 36 sessions |

| Hospital Garcia de Orta | Almada | 3 times a week, 12 weeks; 36 sessions |

| Private centers | ||

| Clínica Dr. Dídio de Aguiar | Lisbon | Not specified |

| Instituto do Coração | Lisbon | 3 times a week, 8-12 weeks |

| Faculdade de Motricidade Humana (Corlis) | Lisbon | Phase III only |

| Fisimaia | Maia | Twice a week, 12 weeks; 24 sessions |

| Diprofísio | Porto | 3 times a week, 12 weeks; 36 sessions |

| SAMS | Lisbon | 3 times a week, 12 weeks; 36 sessions |

| Clínica Fisiatria MCCB Dr. Maria do Carmo Aguiar Branco | Gaia | 2-3 times a week; 24-72 sessions |

| Clínica das Conchas | Lisbon | Phase III only |

| Hospital da Luz | Lisbon | 3 times a week; 36 sessions |

| Instituto de Cardiologia Preventiva de Almada | Almada | 3 times a week; 36 sessions |

| Clínica da Cruz Vermelha, Sabrosa | Sabrosa | Twice a week; Minimum 22 sessions |

CAD: coronary artery disease; HF: heart failure.

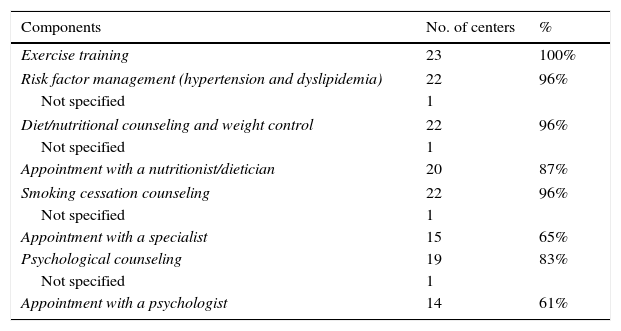

Risk factor management is now offered in almost all centers, having increased from 75% in 2007 to 96%. The other components are available in a significant percentage of centers, as shown in Table 4.

Cardiac rehabilitation program components.

| Components | No. of centers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise training | 23 | 100% |

| Risk factor management (hypertension and dyslipidemia) | 22 | 96% |

| Not specified | 1 | |

| Diet/nutritional counseling and weight control | 22 | 96% |

| Not specified | 1 | |

| Appointment with a nutritionist/dietician | 20 | 87% |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 22 | 96% |

| Not specified | 1 | |

| Appointment with a specialist | 15 | 65% |

| Psychological counseling | 19 | 83% |

| Not specified | 1 | |

| Appointment with a psychologist | 14 | 61% |

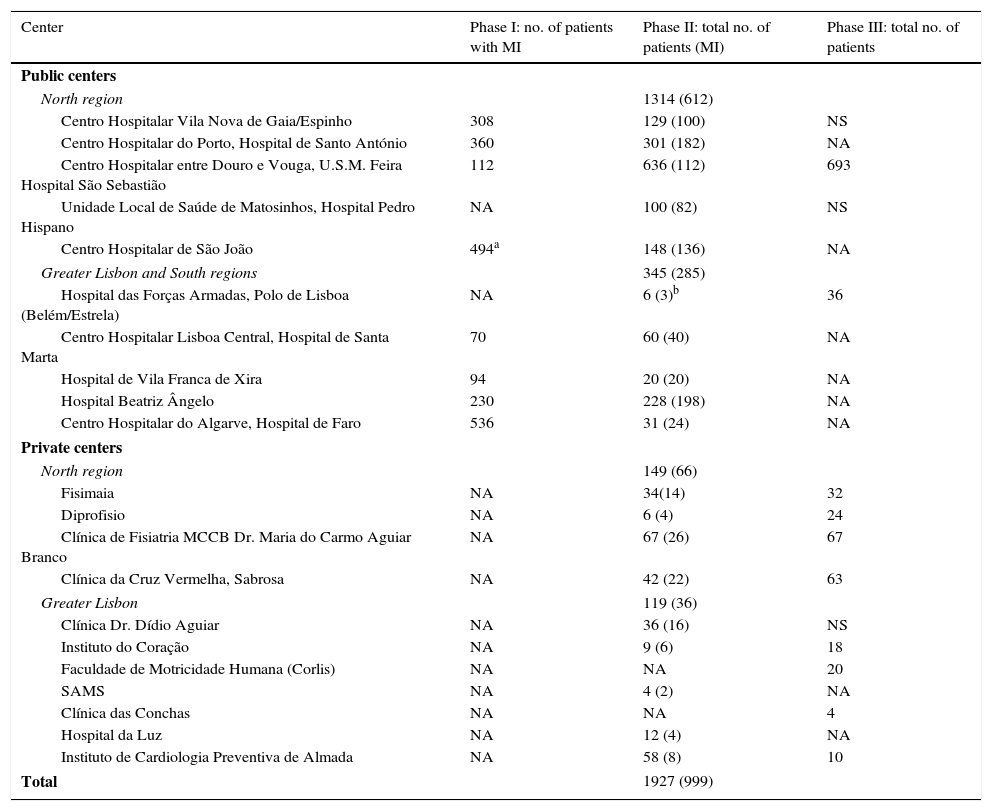

In 2013, 1927 patients participated in phase II CR programs, 1659 in public and 268 in private centers. The number of rehabilitated patients thus tripled in Portugal between 2007 (638) and 2013 (1927). This increase was due mainly to the rise in the number of patients rehabilitated in public centers (from 455 in 2007 to 1659 in 2013). Two factors contributed to this increase: new centers that between them rehabilitated 427 patients; and a tripling of the number rehabilitated in existing centers, from 455 in 2007 to 1232 in 2013. The increase in patients rehabilitated in private centers was less marked (from 183 in 2007 to 268 in 2013) (Table 5).

Total numbers of participants in cardiac rehabilitation programs in Portugal in 2013.

| Center | Phase I: no. of patients with MI | Phase II: total no. of patients (MI) | Phase III: total no. of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public centers | |||

| North region | 1314 (612) | ||

| Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho | 308 | 129 (100) | NS |

| Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Hospital de Santo António | 360 | 301 (182) | NA |

| Centro Hospitalar entre Douro e Vouga, U.S.M. Feira Hospital São Sebastião | 112 | 636 (112) | 693 |

| Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos, Hospital Pedro Hispano | NA | 100 (82) | NS |

| Centro Hospitalar de São João | 494a | 148 (136) | NA |

| Greater Lisbon and South regions | 345 (285) | ||

| Hospital das Forças Armadas, Polo de Lisboa (Belém/Estrela) | NA | 6 (3)b | 36 |

| Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Hospital de Santa Marta | 70 | 60 (40) | NA |

| Hospital de Vila Franca de Xira | 94 | 20 (20) | NA |

| Hospital Beatriz Ângelo | 230 | 228 (198) | NA |

| Centro Hospitalar do Algarve, Hospital de Faro | 536 | 31 (24) | NA |

| Private centers | |||

| North region | 149 (66) | ||

| Fisimaia | NA | 34(14) | 32 |

| Diprofisio | NA | 6 (4) | 24 |

| Clínica de Fisiatria MCCB Dr. Maria do Carmo Aguiar Branco | NA | 67 (26) | 67 |

| Clínica da Cruz Vermelha, Sabrosa | NA | 42 (22) | 63 |

| Greater Lisbon | 119 (36) | ||

| Clínica Dr. Dídio Aguiar | NA | 36 (16) | NS |

| Instituto do Coração | NA | 9 (6) | 18 |

| Faculdade de Motricidade Humana (Corlis) | NA | NA | 20 |

| SAMS | NA | 4 (2) | NA |

| Clínica das Conchas | NA | NA | 4 |

| Hospital da Luz | NA | 12 (4) | NA |

| Instituto de Cardiologia Preventiva de Almada | NA | 58 (8) | 10 |

| Total | 1927 (999) | ||

MI: myocardial infarction; NA: not applicable (this phase not offered); NS: not specified.

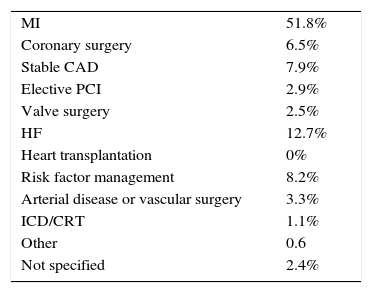

CAD was the most common referral diagnosis, accounting for over two-thirds of admissions: 51.8% following MI, 6.5% after coronary surgery, 2.9% after elective percutaneous coronary intervention, and 7.9% due to stable CAD. HF was the reason for referral in 12.7% of patients, followed by risk factor management in 8.2% and arterial disease or vascular surgery in 3.3% (Table 6).

Distribution by diagnosis of participants in phase II cardiac rehabilitation programs.

| MI | 51.8% |

| Coronary surgery | 6.5% |

| Stable CAD | 7.9% |

| Elective PCI | 2.9% |

| Valve surgery | 2.5% |

| HF | 12.7% |

| Heart transplantation | 0% |

| Risk factor management | 8.2% |

| Arterial disease or vascular surgery | 3.3% |

| ICD/CRT | 1.1% |

| Other | 0.6 |

| Not specified | 2.4% |

CAD: coronary artery disease; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Comparison with the 2007 survey showed that MI continued to be the predominant referral diagnosis, with similar percentages (50% in 2007 and 51.8% in 2013), while HF, a more recent indication for CR, increased from 5% to 12.7%.

Based on DGS data for hospital morbidity, 12 832 patients were discharged after MI in 2013.17 According to the results of the present survey, 999 patients with MI were admitted to phase II CR programs in that year, corresponding to 8%, up from 3% in 2007.

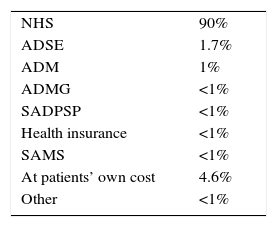

Funding bodiesGiven that most patients attending phase II CR programs in 2013 did so in public centers, the national health system was the funding body in 90% of cases. The patients themselves bore the cost in 4.6%, ADSE in 1.7%, ADM in 1%, and other health subsystems such as ADMG, SADPSP, SAMS, health insurance or other in <1% each (Table 7).

Funding bodies for phase II cardiac rehabilitation programs.

| NHS | 90% |

| ADSE | 1.7% |

| ADM | 1% |

| ADMG | <1% |

| SADPSP | <1% |

| Health insurance | <1% |

| SAMS | <1% |

| At patients’ own cost | 4.6% |

| Other | <1% |

NHS: national health system.

Only ten centers responded to this item on the questionnaire, five public and five private, but together these accounted for around 60% of patients attending phase II cardiac rehabilitation programs in 2013.

The present survey identified 23 centers in Portugal offering CR programs in 2014, 12 public and 11 private. This represents a significant increase in the number of public centers over the years, from only two in 1998 (Belém Military Hospital, a pioneering public center that began activity in 1988, and Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia, which began offering CR in 1993) to seven in 2004 and 2007, and 12 in 2014.

There was also a significant rise in the number of patients attending phase II programs, the number tripling between 2007 and 2013, from 683 to 1927. Public centers were largely responsible for this increase, rehabilitating 86% of patients, while private centers rehabilitated only 14%. It was not possible to compare patient numbers for the other CR program phases since these were not quantified in earlier surveys.

MI was the most common diagnosis of participants in CR programs, as in previous surveys. Nevertheless, based on DGS data for hospital morbidity, only 8% of MI patients attended phase II programs in Portugal in 2013. This figure, while clearly better than the 3% identified in the 2007 survey, is still lower than the European average.18 In the European Cardiac Rehabilitation Inventory Survey by Bjarnason-Wehrens et al. in 2009, the mean percentage of eligible patients admitted to CR programs in Europe was 30%, while in the UK, Sweden, Luxemburg and Germany the figure was around 50%. Almost half of the countries included in this survey had legislation regarding phase II CR; for example, in Germany, CR following MI has been guaranteed by law since 1974, and has led to the development of a network of 170 CR centers.18 There are several reasons for the low percentage of patients undergoing CR in Portugal, including an insufficient number of CR centers and their asymmetrical geographical distribution, incompatibility between program timetables and working hours, economic restraints (such as patients’ share of treatment costs and travel expenses), and a lack of awareness of CR on the part of patients and physicians, leading to low rates of referral.

We hope that publishing the results of the latest survey will encourage the establishment of new CR programs, particularly in centers outside of Porto and Lisbon, thus helping to reduce the considerable asymmetry in geographical distribution that currently exists. It is essential to develop a national network of centers offering CR. All hospitals with cardiology departments should have phase I and II programs,19 and be actively involved in phase III, possibly in association with health centers in the community. Most hospitals already have the various health professionals needed to form a multidisciplinary CR team, but these are usually occupied in other duties and few have specific training in this area. As well as training, investment is also needed in facilities and equipment such as ergometers and telemetry monitors, and so the involvement and commitment of health authority decision-making bodies are also essential.

At the same time, it is important that existing CR programs should continue to grow and that more eligible patients with diagnoses other than MI, notably those who have undergone cardiac surgery or elective percutaneous coronary intervention, should be referred, while not neglecting those with HF and those with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs).

Improved access to CR could in some cases be achieved by implementing home-based programs based on the model widely used in the UK. Such programs, designed for low-risk patients, are structured interventions with regular patient monitoring, including visits by CR team members to the patient's home and contact by telephone or the internet. A recent review demonstrated that home-based programs appear to be equally effective as those offered in hospitals or clinics. There were no significant differences in outcomes up to 12 months of follow-up or in healthcare costs.20 Each center should develop the model most suited to their particular situation.

Another way to improve access and adherence to CR would be to pass specific legislation promoting secondary prevention and CR programs aimed at, for example, reducing or abolishing patients’ share of treatment costs, subsidizing travel expenses and scheduling sessions to fit in with working hours.

Initiatives to raise awareness of and provide training in CR also have an important role, both for the general population and patients and for health professionals, particularly physicians. Including a CR component in the training program of cardiology interns would dispel the skepticism and unfounded concerns that still exist and help to make CR an integral part of the spectrum of cardiovascular disease treatment.

Although much remains to be done, the latest survey identified several positive developments that show that CR in Portugal is consistently evolving in line with international guidelines. The programs have become more comprehensive: besides exercise training, almost all now include risk factor management. Other components such as advice on diet/nutrition and weight control, psychosocial assessment and smoking cessation counseling are available in a large proportion of centers. Patients with conditions that are more recent indications for CR, including those with CRT devices or ICDs, are now being admitted to CR programs and the percentage of patients with HF as the referral diagnosis has risen from 5% to 12.7%. Most phase II programs last 8-12 weeks (two or three sessions a week, making a total of 24-36 sessions), as found in the rest of Europe18 and the US,21 where Medicare has provided coverage for up to three weekly sessions for 12 weeks after MI, coronary bypass surgery or stable coronary disease since 1982, and coverage was later expanded to other indications.21 Shorter programs offer less opportunity for sustained lifestyle changes.

Despite the positive developments in Portugal, challenges remain. Investment in cardiovascular disease prevention is essential and CR plays a crucial role in this. Decision-making bodies should be made more aware of the importance of CR programs, which have been shown to be cost-effective.22,23

ConclusionsThe number of centers offering CR programs and the volume of patients rehabilitated increased considerably between 2007 and 2013-14. The percentage of MI patients referred for CR increased from 3% to 8%, and HF patients are increasingly admitted to such programs. The latest survey showed that CR has shown consistent growth and evolved in line with international guidelines. Nevertheless, Portugal remains below the European average in CR, and further improvements are still needed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The Working Group on Exercise Physiology and Cardiac Rehabilitation thanks the coordinators of CR programs for their cooperation in supplying the data for the survey, without which this study would not have been possible.

Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho – Dr. Madalena Teixeira

Centro Hospitalar do Porto, H. S. António – Dr. Sofia Viamonte and Dr. Preza Fernandes

Centro Hospitalar Entre Douro e Vouga, Unidade S.M. Feira, H. São Sebastião – Dr. Catarina Aguiar Branco

Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos, Hospital Pedro Hispano – Dr. Paula Almeida

Centro Hospitalar São João – Dr. Afonso Rocha

Hospital de Vila Franca de Xira – Dr. Luís Nuno Batista

Centro Hospitalar Algarve, Hospital de Faro – Dr. Salomé Pereira

Hospital Beatriz Ângelo – Dr. Miguel Almeida Ribeiro

Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte, Hospital Pulido Valente – Dr. Machado Rodrigues

Hospital Garcia de Orta – Dr. Maria Luísa Bento

Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Hospital de Santa Marta – Dr. Ana Abreu

Hospital das Forças Armadas Polo de Lisboa – Dr. Conceição Silveira

Clínica Dr. Dídio de Aguiar – Dr. Joaquim Pestana Aguiar

Instituto do Coração – Dr. Miguel Mendes

Faculdade de Motricidade Humana (Corlis) – Prof. Helena Santa-Clara

Fisimaia – Dr. Paulo Fontes

Diprofísio – Dr. Madalena Teixeira

SAMS – Dr. Ana Abreu, Dr. Cecília Vaz Pinto

Clínica Fisiatria MCCB Dr. Maria do Carmo Aguiar Branco – Dr. Catarina Aguiar Branco

Clínica das Conchas – Dr. Jorge Ruivo

Hospital da Luz – Dr. Daniel Ferreira

Instituto de Cardiologia Preventiva de Almada – Prof. Manuel Carrageta

Clínica da Cruz Vermelha, Sabrosa – Nurse Fátima Marques and Dr. Helder Ribeiro

Please cite this article as: Silveira C, Abreu A. Reabilitação cardíaca em Portugal. Inquérito 2013-2014. Rev Port Cardiol. 2016;35:659–668.