Very late stent thrombosis is a rare but devastating complication after percutaneous coronary revascularization. Pathological studies have demonstrated that neoatherosclerosis plays a major role in certain patients with very late stent thrombosis. Optical coherence tomography is able to unravel the underlying pathophysiology and may be used to select the best treatment option. This case report describes the use of a bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) in a patient suffering from very late stent thrombosis due to a complicated plaque in the setting of intrastent neoatherosclerosis. To our knowledge, this therapeutic strategy has not been previously reported in patients suffering from very late stent thrombosis. In this scenario, BVS implantation might represent an attractive strategy in selected patients.

A trombose de stent muito tardia é uma complicação rara mas preocupante após a revascularização coronária percutânea. Estudos patológicos têm demonstrado que a neoaterosclerose desempenha um papel importante em doentes selecionados com trombose de stent muito tardia. A tomografia de coerência ótica contribui para a compreensão da fisiopatologia subjacente, permitindo selecionar a melhor opção de tratamento. No presente caso descrevemos a utilização de um stent vascular bioabsorvível num doente que apresentava trombose de stent muito tardia devido a placa complexa no contexto de neoaterosclerose intrastent. De acordo com a nossa experiência, esta estratégia terapêutica não tem sido apresentada em doentes com trombose de stent muito avançada. Neste cenário, a implantação de suportes vasculares bioabsorbíveis pode representar uma estratégia atrativa em doentes selecionados.

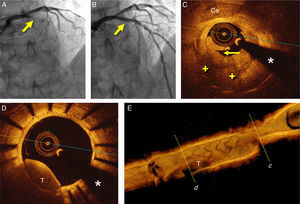

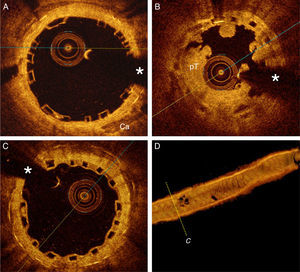

A 52-year-old man with hyperlipidemia was admitted for an episode of prolonged chest pain. The electrocardiogram showed anterior ST-segment elevation from V1 to V3. Eight years before he had suffered an anterior myocardial infarction and a paclitaxel-eluting stent was implanted in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Since then, the patient had been on aspirin and atorvastatin with adequate lipid control. Emergent coronary angiography revealed a complete occlusion (100%, TIMI 0) of the most proximal segment of the stent (Figure 1A). Thromboaspiration was successful in retrieving some red thrombus and in obtaining TIMI 3 coronary flow. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) disclosed complicated in-stent neoatherosclerosis characterized by a large and heterogeneous intrastent plaque with a large lipid pool. Near the area showing the minimal lumen diameter a ruptured fibrous cap associated with white and red thrombi was identified (Figure 1C). In some segments the stent struts could hardly be visualized as the result of significant shadowing caused by the red thrombus or the attenuation induced by lipid plaque. In addition, relatively large, residual red thrombi were also detected in other segments of the stent (Figure 1D and E). The rest of the stent was well covered by homogeneous and bright neointima. There was moderate stent underexpansion but no evidence of uncovered struts or malapposition was detected along the stent. Multiple high-pressure dilatations were performed with a 3 mm non-compliant balloon, with clear lumen improvement but still with a suboptimal angiographic result (intrastent haziness with residual stenosis). A 3.0 mm bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was implanted and subsequently postdilated with a 3.25 mm non-compliant balloon at 20 bar, with an excellent final angiographic result (Figure 1B). Repeat OCT disclosed a properly apposed and expanded device. The characteristic image of the BVS struts (box-like appearance without dorsal shadowing) was clearly identified against the underlying residual neointimal or atherosclerotic tissue over the underlying metallic stent (bright struts with clear-cut posterior shadow) (Figure 2A). There was a moderate rise in cardiac enzymes (peak high-sensitive troponin T 1115 ng/l, peak creatinine kinase 309 U/l) but the clinical course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on aspirin and prasugrel three days later. Unfortunately, three months later the patient himself decided to stop dual antiplatelet therapy. After four days without medication, he suffered a new anterior myocardial infarction. Emergent coronary angiography revealed a thrombosis of the BVS, which was successfully treated with thromboaspiration and dilatation with a non-compliant balloon (Figure 2B). Six months later the patient remains asymptomatic with good adherence to treatment. A scheduled coronary angiography at this time confirmed an excellent result in the target segment. OCT showed a well expanded and apposed BVS with complete neointimal coverage (Figure 2C and D).

(A) Coronary angiography in cranial view showing the occluded left anterior descending coronary artery (arrow); (B) final angiographic result after bioresorbable vascular scaffold deployment; (C) optical coherence tomography (OCT) image after thrombus aspiration showing heterogeneous intrastent tissue with large lipid pools (+). Some stent struts are poorly detected due to attenuation. There is also calcified tissue (Ca) surrounding some struts. Note plaque rupture (arrow); (D) OCT image after thrombus aspiration showing residual red thrombus (T) in an area with complete neointimal coverage. (*) denotes wire artifact; (E) 3D reconstruction of OCT image after thrombus aspiration with severe stenosis due to intrastent tissue (c) and residual red thrombus (T) (d).

(A) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings after bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) implantation. The device was fully expanded and apposed. The metallic struts of the underlying stent are clearly detected (posterior shadow) in the far field; (B) OCT findings during BVS thrombosis, with large platelet-rich thrombus (pT) occupying the lumen and the characteristic box-like appearance of the BVS struts; (C) OCT after six months. Notice complete neointimal coverage of struts. (*) denotes wire artifact; (D) 3D reconstruction of OCT image after six months.

Very late stent thrombosis is a rare but devastating complication after percutaneous coronary revascularization. Stent thrombosis may be due to a mechanical problem such as stent malapposition or underexpansion. On the other hand, pathological studies have demonstrated that neoatherosclerosis plays a major role in certain patients with very late stent thrombosis.1 Interestingly, neoatherosclerosis occurs not only more frequently but also earlier in patients treated with drug-eluting stents compared with those treated with bare-metal stents.1 When the thrombosis is related to stent malapposition or underexpansion, balloon angioplasty without stent deployment is sufficient in most cases. However, the therapy of choice for patients presenting with very late in-stent restenosis or very late stent thrombosis as a result of neoatherosclerosis remains unclear.2,3 In this context the use of BVS is a potentially attractive strategy to avoid the implantation of an additional metal layer while ensuring an optimal acute result and benefiting from their unique antirestenotic efficacy; in addition, they may promote plaque stability and passivation of vulnerable plaques by providing a uniform homogeneous neointimal layer.4 In this regard, some preliminary reports have suggested the value of BVS in patients with in-stent restenosis.5 However, the use of BVS in patients with very late stent thrombosis has not been previously reported. Currently, neoatherosclerosis may be readily recognized using OCT at a resolution of 15 μm.3 This technique is able to unravel the underlying pathological substrate in patients presenting with stent failure. The unique insights provided by OCT may help to tackle underlying mechanical problems such as stent malapposition or underexpansion and neoatherosclerosis, and also to optimize BVS deployment.6,7

Our findings suggest the value of BVS for the treatment of selected patients suffering from very late stent thrombosis as a result of neoatherosclerosis. However, only prospective studies will be able to establish the potential role of this novel form of therapy in this challenging anatomic scenario. In addition, the subsequent episode of BVS thrombosis, which in our case was closely related to lack of adherence to prescribed medications, reminds us of the important role of patient education and counseling to ensure the maintenance of appropriate dual antiplatelet therapy.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.