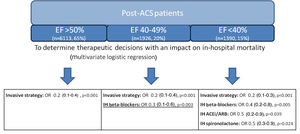

We read with interest the article by Velásquez-Rodríguez et al. published in the April 2021 issue of the Journal,1 which analyzes the impact of beta-blocker (BB) therapy in post-acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. In this important study, the population consisted of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients divided into two groups according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): ≤40% vs. >40%. The impact of BB therapy in the ≤40% population is well known, and current guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) includes it as the first-line treatment to reduce heart rate.2 The real challenge is to understand the impact of BB therapy in currently treated post-ACS patients with LVEF >40%, since the main studies were performed in the pre-revascularisation era and the role of BB therapy in patients treated according to contemporary practice has been questioned.3 Our team has previously published a study investigating the therapeutic impact on in-hospital mortality in currently treated post-ACS patients (n=9429) stratified according to LVEF, adding a third group – patients with mid-range LVEF, between 40 and 50% (n=1926, 20%).4 Regarding the group with low LVEF, our results support the conclusions achieved by Velásquez-Rodríguez et al., with BB therapy having an impact in reducing in-hospital mortality. However, in the intermediate LVEF group, BB therapy also had an impact on in-hospital mortality. In patients with LVEF >50% there was no benefit from BB therapy (Figure 1).4 Similar findings were also seen in the Japanese CHART-2 study.5

In the study by Velásquez-Rodríguez et al., application of other forms of GDMT was lower than expected in the no-BB group (69.3% were on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors). However, in our study, all GDMTs were used very frequently, and although other forms of ACS were included, coronary angiography was performed in >90% of the overall population.6 Only 6.2% of the population analyzed by Velásquez-Rodríguez et al. had atrial fibrillation, while in our study atrial fibrillation was diagnosed in less than 10% of the overall population, and thus its deleterious effects on BB efficacy may not have had a significant impact in either study.4 Neither study analyzed BB dosages, but a previous study by Ibrahim et al. assessed dosing and concluded that a higher dosage was only modestly beneficial in improving prognosis.7 A previous individual patient data meta-analysis by Cleland et al. including 11 trials also reinforced our conclusions, showing that BB therapy improved LVEF for patients in sinus rhythm and with LVEF <40%, and that for patients in the 40-50% range it appeared more likely to help than to harm.8

In conclusion, it seems that as LVEF begins to fall, the margin for therapeutic benefit increases (Figure 1). The ideal cut-off for each GDMT is difficult to attain, but according to both these recent results, BB therapy may in fact start to be beneficial sooner than other GDMTs,4 at least for patients in sinus rhythm. This is a burning question that should be answered through future randomized controlled trials such as the ongoing REBOOT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03596385).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.