Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in Portugal and atherosclerosis is the most common underlying pathophysiological process. The aim of this study was to quantify the economic impact of atherosclerosis in Portugal by estimating disease-related costs.

MethodsCosts were estimated based on a prevalence approach and following a societal perspective. Three national epidemiological sources were used to estimate the prevalence of the main clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis. The annual costs of atherosclerosis included both direct costs (resource consumption) and indirect costs (impact on population productivity). These costs were estimated for 2016, based on data from the Hospital Morbidity Database, the health care database (SIARS) of the Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley including real-world data from primary care, the 2014 National Health Interview Survey, and expert opinion.

ResultsThe total cost of atherosclerosis in 2016 reached 1.9 billion euros (58% and 42% of which was direct and indirect costs, respectively). Most of the direct costs were associated with primary care (55%), followed by hospital outpatient care (27%) and hospitalizations (18%). Indirect costs were mainly driven by early exit from the labor force (91%).

ConclusionsAtherosclerosis has a major economic impact, being responsible for health expenditure equivalent to 1% of Portuguese gross domestic product and 11% of current health expenditure in 2016.

As doenças cardiovasculares são a principal causa de morte em Portugal, sendo a aterosclerose o processo fisiopatológico subjacente mais comum. O objetivo deste estudo foi quantificar o impacto económico da aterosclerose em Portugal através da estimação dos custos associados.

MétodosA estimativa dos custos foi realizada na ótica da prevalência e na perspetiva da sociedade. A prevalência das principais manifestações focais da aterosclerose foi estimada com recurso a três fontes epidemiológicas nacionais. O custo anual da aterosclerose incluiu custos diretos (consumos de recursos) e indiretos (impacto na produtividade da população). Estes custos foram estimados para o ano de 2016 com base nos dados da Base de Dados de Morbilidade Hospitalar, do Sistema de Informação da Administração Regional de Saúde de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo que integra informação da prática clínica real em ambiente de cuidados de saúde primários, do Inquérito Nacional de Saúde de 2014 e na opinião de Peritos.

ResultadosO custo da aterosclerose em 2016 totalizou cerca de 1,9 mil milhões de euros (58% e 42% correspondendo a custos diretos e indiretos, respetivamente). A maior parte dos custos diretos esteve associada aos cuidados de saúde primários (55%), seguindo-se o ambulatório hospitalar (27%) e, por último, os episódios de internamento (18%). Os custos indiretos foram principalmente determinados pela não participação no mercado de trabalho (91%).

ConclusõesA aterosclerose apresenta um importante impacto económico, correspondendo a uma despesa equivalente a 1% do Produto Interno Bruto nacional e a 11% da despesa corrente em saúde, em 2016.

Atherosclerosis is a disease of the elastic arteries (large and medium caliber) and the muscular arteries that is anatomopathologically characterized by plate-shaped lesions known as atheromas or plaques.1 Depending on the arterial territory involved it can have different clinical manifestations, of which the best-known are ischemic heart disease (IHD), ischemic cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and peripheral arterial disease (PAD).1 These manifestations are part of the group that make up cardiovascular disease, which remains the leading cause of death worldwide,2 in Europe3 and in Portugal (27% of all deaths in 20174). In addition to the high mortality related to atherosclerosis, it is also associated with significant morbidity.5 Overall, therefore, atherosclerosis has a considerable impact on health at both individual and populational levels, and is expected to result in economic consequences due to the associated resource consumption, not only for treatment of established atherosclerosis, but also for disease prevention.

The aim of this study was to estimate the costs of atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal, in order to quantify its economic impact from the standpoint of the country’s National Health Service.

MethodsThe study population consisted of the resident population of mainland Portugal aged ≥18 years. Costs were estimated based on a prevalence approach, i.e. costs associated specifically with atherosclerosis during 2016 (the most recent year for which data were available at the time of the study). A societal perspective was adopted, which considered direct costs (resource consumption) and indirect costs (impact on population productivity) associated with the disease. The manifestations of atherosclerosis – IHD (myocardial infarction [MI], chronic coronary artery disease [CAD] and ischemic heart failure [HF]), ischemic CVD (ischemic stroke), and PAD – were analyzed separately since they have different economic and social impacts.

PrevalenceThe prevalence of the clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis was estimated on the basis of data from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey6 carried out by the National Health Institute Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA), an observational study by Menezes et al.,7 and the EPICA (Epidemiologia da Insuficiência Cardíaca e Aprendizagem) study.8

Affirmative answers in the National Health Survey to the question whether the respondent had had any of the following conditions in the previous 12 months – “myocardial infarction (heart attack) or chronic consequences of myocardial infarction”, “coronary disease or angina”, or “stroke or chronic consequences of stroke” – were used to estimate the self-reported prevalence of MI, chronic CAD and stroke, respectively.6 The prevalence of ischemic stroke was estimated assuming that 83% of cases of stroke are ischemic in nature, on the basis of the distribution of cases in the Hospital Morbidity Database (BDMH) of the Central Administration of the National Health System (ACSS) for 2016.12

The study by Menezes et al.7 was used to calculate the prevalence of PAD and the proportion of symptomatic cases. The study aimed to determine the prevalence of PAD in the Portuguese population and to assess its relationship with demographic and anthropometric characteristics, risk factors and symptoms. Information was collected via a questionnaire applied to a total of 5731 individuals aged over 50 years in mainland Portugal. The diagnosis of PAD was obtained by measuring the ankle-brachial index.7

The prevalence of ischemic HF was estimated using data from the EPICA study on individuals with HF and suspected coronary disease.8 A conservative approach was adopted in which only New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes II-IV were included, the same criterion as that used by the authors of the present study for estimating the costs and disease burden of HF in Portugal.9,10

The prevalence of each of the clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis in 2016 was estimated by applying the prevalences (by demographic cell) obtained from the original sources cited above to the population of mainland Portugal in that year.11

Direct costsThe direct costs analyzed in this study included medical costs (costs of hospitalizations and outpatient care, including those arising from hospital outpatient care and primary health care [PHC]), and non-medical costs, particularly those related to transportation.

Hospitalization costsConsumption of resources due to hospitalizations for atherosclerotic diseases was estimated based on data from the BDMH hospital morbidity database for 2016.12

Episodes of hospitalization in the BDMH were identified using the ninth (ICD-9-CM) and tenth (ICD-10-CM) revisions of the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification. All episodes with a principal diagnosis of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes under “Ischemic heart diseases” and “Cerebrovascular diseases” of ischemic etiology were considered to be IHD (MI and chronic CAD) and ischemic CVD, respectively. Cases of PAD were identified by means of the ICD-9-CM codes published by Agarwal et al.13 and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.14 Supplementary Table S1 lists the ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes used to identify hospitalizations.

The costs of hospitalizations arising from IHD, ischemic CVD and PAD were calculated as the sum of the costs of episodes identified by the BDMH microdata. For each episode the price used was that set out in Order in Council no. 234/2015, and thus reflects the different rules used for calculating these prices, including the severity of the episode.

For ischemic HF, the cost of hospitalization for HF previously estimated by the authors was applied in proportion to the prevalence of ischemic HF in NYHA classes II–IV, which, according to the EPICA study, is 36%.8 The cost of ischemic HF hospitalization for episodes identified with the “Cardiac transplantation” procedure code included funds attributed to public or private entities authorized to perform collection and transplantation under Order no. 7215/2015 (€18 018.62 per episode).

Hospital outpatient costsThe BDMH was also used to identify hospital outpatient episodes coded by Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG), using the relevant ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes (Supplementary Table S1). The costs of these episodes were calculated using the same method as for hospitalizations.

Consumption of other resources (medical and non-medical) in the hospital outpatient setting that are not associated with a DRG code and are therefore not found in the BDMH was estimated by elicitation from an expert panel. The eleven experts, selected to represent the country’s different regions, responded independently to specific questions via an emailed questionnaire on patterns of consumption of medical care nationwide (consultations, complementary diagnostic and therapeutic procedures including physical medicine and rehabilitation, support products, and social responses). Their responses were analyzed and simple means of the values were calculated, excluding outliers by using trimmed means, a necessary precaution when some values are very far from others.

The mean resource consumption by a patient undergoing hospital outpatient care could thus be calculated. On the basis of these figures, the number of urgent (transportation for emergency departments [EDs]) and non-urgent (transportation for medical consultations) journeys required in this setting could be estimated.

Health resources were valued according to the prices set by Orders in Council nos. 254/2018 and 353/2017. The costs of patient transportation were those published by NOVA Healthcare Initiative Research for expenditure on transportation by the patient when going to the hospital.15 The total cost of each atherosclerosis manifestation was calculated as the mean cost per patient multiplied by the prevalence of each disease, taking into account the proportion of patients who received hospital outpatient care as set by the expert panel.

Outpatient costs in primary health careA cross-sectional study was performed to estimate resource consumption in PHC, by consulting the health care database (SIARS) of the Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley (ARSLVT).16 SIARS functions as a repository of administrative, clinical and demographic data on users of the health centers of a specific region. In 2016, the ARSLVT SIARS recorded data on 1 879 705 users aged 18 years or over. Supplementary Table S2 presents the selection criteria used to identify the subpopulation to be analyzed with regard to resource consumption related to atherosclerosis. This analysis was used to determine the number of consultations and diagnostic and therapeutic procedures relevant to cardiovascular disease (excluding physical medicine and rehabilitation) and to directly calculate the costs of medication consumed in the outpatient setting by patients with atherosclerosis and charged to the ARSLVT with atherosclerosis irrespective of where they were prescribed (PHC, hospital outpatient clinics or private facilities). It was assumed that these data reflected the consumption of medication by patients with atherosclerosis in the outpatient setting. However, this is a conservative approach, since it does not consider medication consumed by patients followed only in the hospital outpatient setting. The data from SIARS were also used to estimate the number of non-urgent journeys (transportation for medical consultations) required by patients followed in PHC. The costs calculated for PHC in the ARSLVT were extrapolated to mainland Portugal by multiplying them by 2.6 (the ratio of all adults resident in mainland Portugal in 2016 to the number registered in the ARSLVT).

Unit costs were based on previously used sources to calculate resource consumption in the hospital outpatient setting. Supplementary Tables S3–S8 show all the unit costs used in this study.

Indirect costsThe only indirect costs considered in this study were those associated with productivity loss due to disease, excluding loss due to premature death. Estimates of productivity losses were obtained by calculating how the major clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis affect absenteeism of employed patients and non-participation in the labor market due, for example, to early exit from the labor force because of long-term disability.

Absenteeism and non-participation in the labor market due to MI, chronic CAD or stroke were estimated on the basis of the microdata from the 2014 National Health Survey. Absenteeism was estimated by calculating employment rates in the population aged under 65 years with MI (39.2% of men and 15.9% of women), with chronic CAD (53.8% of men and 35.3% of women) and with stroke (40.5% of men and 33.9% of women). In order to assess non-participation in the labor market, the impact of these diseases was estimated by measuring the difference between the employment rates of individuals aged under 65 years with a self-reported history of MI, chronic CAD or stroke and the employment rates of those without such a history, with the same gender and age-group distribution. The difference was estimated at 21% in men and 35% in women for MI, 7% in men and 20% in women for chronic CAD, and 23% in men and 19% in women for stroke (considered to be ischemic in nature).

HF and PAD were not among the self-reported diseases in the National Health Survey. Each of the three NYHA functional classes (II, III and IV) was therefore considered separately, with patients aged between 25 and 65 years being distributed by these classes in accordance with the EPICA study. No patients aged between 25 and 65 years were identified as being in NYHA class IV, and so no patients in this class were included in the estimates of indirect costs. Regarding the 22% of patients with NYHA class III ischemic HF, it was assumed that their non-participation in the labor market and employment rate as an indicator of absenteeism would be similar to those with a history of MI. For the 71% of patients with NYHA class II ischemic HF a conservative approach was taken by assuming that in this group there was no difference in participation in the labor market compared to the general population (76.0% in men and 69.9% in women). Employment rates for the general population were obtained from Statistics Portugal (INE) for the third quarter of 2018.17 For PAD, a conservative approach was again adopted, that there was no difference in participation in the labor market compared to the general population.

Two reasons for absenteeism were considered: absence from work due to consultations, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and ED visits without admission; and absence due to hospitalization and convalescence. It was assumed that for every consultation (in whatever specialty), diagnostic and therapeutic procedure and ED visit without admission, the patient lost a half, a quarter, or an entire day of work, respectively. For time lost due to hospitalization and convalescence, the time lost for convalescence was considered to be equal to the length of hospital stay.

The monetary value of this productivity loss was calculated according to human capital theory,18 using the mean productivity of workers estimated from employers' charges. The mean annual earnings in mainland Portugal were calculated as the mean monthly salary published by the Office of Strategy and Planning of the Ministry of Labor, Solidarity and Social Security (€1266.3 for men and €1011.2 for women),19 plus employers’ social security contributions at a rate of 23.75%, and multiplied by 14 to include holiday and Christmas bonuses. Daily productivity lost through absenteeism due to medical consultations and exams was calculated by dividing the mean annual salary by 230 (the number of working days per year, since consultations and exams only take place on these days). Only ED visits occurring during working hours were considered; these were assumed to represent 50% of all ED episodes based on national figures for ED visits for all causes.20 For absenteeism related to hospitalization and convalescence, the mean annual salary was divided by 365 (since hospitalization and convalescence can occur on any day of the week).

Supplementary Table S9 summarizes the information used to calculate indirect costs related to productivity loss due to absenteeism in patients with atherosclerosis.

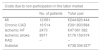

ResultsPrevalenceTable 1 presents the estimated prevalence of the different clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis for mainland Portugal in 2016 in accordance with the sources used.11

Estimated prevalence of ischemic heart disease, stroke and peripheral arterial disease in mainland Portugal in 2016.

| MI | Chronic CAD | Ischemic HF | Stroke | PAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INS 20146 | 151 678a | 375 278a | NR | 164 829b | NR |

| Menezes et al.7 | NR | NR | NR | – | 248 093c |

| EPICA study8 | NR | NR | 91 046d | NR | NR |

CAD: coronary artery disease; IHD: ischemic heart disease; INS: National Health Survey; MI: myocardial infarction; NR: not reported; PAD: peripheral arterial disease.

The overall prevalence of symptomatic atherosclerosis was estimated at 742 709 adults in mainland Portugal. This figure is lower than the sum of the prevalences of the separate manifestations of the disease, because in some patients more than one form of the disease coexisted.

Direct costsHospitalization and hospital outpatient costsAnalysis of the 2016 BDMH, using the codes listed in Supplementary Table S1, identified 54 813 hospitalizations for IHD, ischemic CVD and PAD, in addition to 12 809 hospitalizations for ischemic HF.9 The total cost of these hospitalizations was €199 471 561 in 2016 (Table 2).

Hospitalization costs (identified in the Hospital Morbidity Database, 2016).

| No. of episodes | Mean cost per episode | Total costc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHDa | 23 125 | €3009 | €69 574 908 |

| Ischemic HFb | 12 809 | €3270 | €41 891 362 |

| Ischemic CVD | 24 863 | €2491 | €61 940 359 |

| PAD | 6825 | €3819 | €26 064 932 |

| Atherosclerosis | 67 622 | – | €199 471 561 |

CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HF: heart failure; IHD: ischemic heart disease; PAD: peripheral arterial disease.

Number of episodes and costs of ischemic HF previously estimated by the authors.9 The cost of hospitalizations identified as “Heart transplantation” includes funds attributed to public or private entities authorized to perform collection and transplantation under Order no. 7215/2015 (€18 018.62 per episode).

Regarding hospital outpatient costs, analysis of the 2016 BDMH identified 7596 hospital outpatient episodes, to which were added 224 episodes of ischemic HF.9 The total estimated cost of all these hospital outpatient episodes in 2016 was €9 960 966 (Table 3).

Hospital outpatient costs (identified in the Hospital Morbidity Database, 2016).

| No. of episodes | Mean cost per episode | Total cost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHDa | 7397 | €1230 | €9 095 144 |

| Ischemic HFb | 224 | €1359 | €304 267 |

| Ischemic CVD | 6 | €2723 | €16 341 |

| PAD | 193 | €2825 | €545 214 |

| Atherosclerosis | 7820 | – | €9 960 966 |

CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HF: heart failure; IHD: ischemic heart disease; PAD: peripheral arterial disease.

Other hospital outpatient costs were estimated based on health care consumption patterns as defined by the expert panel and corresponding unit costs. They included ED visits without admission, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures during hospital follow-up (and not included in the outpatient episodes identified in the BDMH), such as laboratory tests and exams assessing cardiac function, and consultations. The cost of travel to and from consultations was added to this total.

Consumption of medication and corresponding costs were estimated by direct consultation of SIARS. These costs are not included under this heading but under the next (outpatient costs in PHC).

Table 4 presents the hospital outpatient costs additional to those calculated directly from the 2016 BDMH. The total cost of each manifestation of atherosclerosis was estimated as the mean cost per patient multiplied by the prevalence of each manifestation and considering the proportion of patients treated in hospital outpatient care, calculated as the percentage of patients with hospital consultations defined by the expert panel. The higher mean costs of ischemic CVD is due to the extra cost of physical medicine and rehabilitation for this condition.

Hospital outpatient costs (not associated with a Diagnosis-Related Group code).

| Prevalence in hospital outpatient carea | Mean cost per patientb | Total cost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MI | 101 252 | €320 | €32 433 356 |

| Chronic CAD | 159 493 | €220 | €35 052 149 |

| Ischemic HF | 40 912 | €556 | €22 754 011 |

| Ischemic CVD | 83 239 | €2303 | €191 689 919 |

| PAD | 71 666 | €631 | €45 202 787 |

| Total | €289 049 959c |

CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HF: heart failure; MI: myocardial infarction; PAD: peripheral arterial disease.

This figure is lower than the sum of the costs for each manifestation because the same individual may present more than one clinical manifestation of atherosclerosis. The cost of a patient with more than one clinical manifestation is assumed to be the highest cost among these different manifestations.

In the case of the total cost of hospital outpatient care not associated with a DRG code (€289 049 959 in 2016; Table 4), the figure is lower than the sum of the costs for each manifestation because the same individual may present more than one clinical manifestation of atherosclerosis. The cost of a patient with more than one clinical manifestation is assumed to be the highest cost among these different manifestations.

Outpatient costs in primary health careThe cross-sectional study of the SIARS data identified a total of 318 692 PHC users with atherosclerosis in the ARSLVT in 2016, corresponding to a total estimated cost of €210 686 792 in that year. Table 5 summarizes the distribution of these costs according to their origin (consultations, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and medication), and distinguishes between preclinical and established disease. The costs for medication cover all consumption in an outpatient setting, including medication prescribed in hospital outpatient care.

Outpatient costs in primary health care (based on SIARS 2016).

| ARSLVT | Total cost in mainland Portugal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of preclinical diseasea | Cost of established diseasea | Total | ||

| Consultations | €22 822 931 | €49 699 638 | €72 522 569 | €191 321 071 |

| Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures | €9 072 780 | €15 304 659 | €24 377 439 | €64 309 880 |

| Medication | €34 650 644 | €79 136 321 | €113 786 965 | €300 180 264 |

| Total | €66 546 355 | €144 140 618 | €210 686 793 | €555 811 214 |

ARSLVT: Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley; SIARS: regional health care database.

Preclinical disease was defined as the presence of ≥3 risk factors in patients with no recorded diagnosis of manifestations of atherosclerosis and not taking antiplatelet or peripheral arterial disease-specific medication (see Supplementary Table S2). This population accounted for 34% of the patients identified in SIARS.

Considering the numbers of patients identified in SIARS with preclinical and established disease (the latter being those diagnosed with one of the three main manifestations of atherosclerosis), a mean cost was obtained for each of these two patient types (Table 6). This cost was 12.6% higher in patients with established disease. Among the three main manifestations, the cost of IHD was the highest, mainly due to the costs of medication.

Mean cost per patient with atherosclerosis (based on SIARS 2016).

| Patients with clinical manifestations | €687 |

| IHD | €808 |

| Ischemic CVD | €695 |

| PAD | €788 |

| Patients without clinical manifestations | €610 |

CVD: cerebrovascular disease; IHD: ischemic heart disease; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; SIARS: regional health care database.

The total cost in mainland Portugal associated with resource consumption for atherosclerosis in PHC was €555 811 214, to which were added the costs of travel to and from consultations (€59 790 304).

The total direct cost of atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal in 2016 was thus around €1.1 billion.

Indirect costsThe indirect cost of atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal in 2016 totaled €810 812 882, of which 91% was due to non-participation in the labor market and the other 9% was attributed to absenteeism due to consultations, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, ED visits without admission, hospitalizations and convalescence. Table 7 details the structure of these indirect costs.

Indirect costs of atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal, 2016.

| Costs due to non-participation in the labor market | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | Total cost | |

| MI | 12 691 | €244 820 444 |

| Chronic CAD | 16 514 | €301 803 884 |

| Ischemic HF | 2473 | €47 061 382 |

| Ischemic stroke | 8971 | €176 159 574 |

| PAD | – | – |

| Subtotal | €738 306 327c | |

| Costs due to absenteeism | ||

|---|---|---|

| Duration, daysa | Total cost | |

| PHC | €27 766 959 | |

| Consultations | 2.2 | €15 725 565 |

| Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures | 1.7 | €12 041 394 |

| Hospital outpatient care | €36 985 050 | |

| MI | 1.9 | €1 551 412 |

| Chronic CAD | 2.4 | €4 097 323 |

| Ischemic HF | 2.4 | €1 297 837 |

| Ischemic stroke | 6.7b | €26 838 741 |

| PAD | 5.4 | €4 335 368 |

| Hospitalizations and convalescence | €7 754 547 | |

| IHD | 10.13 | €1 972 462 |

| Ischemic HF | 20.26 | €3 403 248 |

| PAD | 29.48 | €2 378 837 |

| Subtotal | €72 506 556c | |

| Total indirect costs | €810 812 882 | |

CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; HF: heart failure; IHD: ischemic heart disease; MI: myocardial infarction; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; PHC: primary health care.

Authors’ estimate based on number of consultations, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and hospitalizations.

Adding together all the individual costs listed above gives an estimated total cost of atherosclerosis in 2016 of €1 924 896 887 (Table 8).

Total costs due to atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal in 2016.

| Cost | Percentage of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct costs | €1 114 084 005 | 58% |

| Hospitalizations (BDMH) | €199 471 561 | 10% |

| Hospital outpatient care | ||

| Outpatient episodes (BDMH) | €9 960 966 | 1% |

| Other consumptiona | €289 049 959 | 15% |

| PHC | €615 601 519 | 32% |

| Indirect costs | €810 812 882 | 42% |

| Non-participation in the labor market | €738 306 327 | 38% |

| Absenteeism | €72 506 556 | 4% |

| Total | €1 924 896 887 |

BDMH: Hospital Morbidity Database; PHC: primary health care.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic disease of the arteries that has a significant social impact due to the mortality and morbidity associated with its clinical manifestations, particularly IHD, ischemic CVD and PAD. The aim of the present study was to estimate the costs of atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal in 2016 in order to quantify its economic impact on the country.

This study was based on the prevalence of symptomatic atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal, estimated at 742 709 adults, around 9% of the population. This figure mainly represents the clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis that cause symptoms recognized by patients.

The direct costs (58%, mostly related to outpatient care) and indirect costs (42%, mostly related to non-participation in the labor market) of atherosclerosis in mainland Portugal in 2016 amount to more than €1.9 billion, which is equivalent to 1% of the country’s gross domestic product, 11% of current health expenditure, and a mean annual cost of €237 to every Portuguese adult.

There have been few studies published on the costs associated with atherosclerosis. Vlayen et al.21 performed a study with similar methodology to ours to estimate the cost of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Belgium in 2004. They provided separate estimates for the costs of prevention and screening, preclinical disease, and established disease. When comparing the results of the two studies, we only considered the cost of established disease, since this was the disease form that was best characterized in our study, and excluded transportation costs, since they were not counted in the Belgian study. The total cost of established atherosclerosis in Belgium in 2004 was €2.2 billion, equivalent to €3782 per patient.21 The equivalent sum in Portugal for 2016 was €2215, which is 41% less than in the Belgian study. Bearing in mind inflation during the period between the two studies (12 years) and the purchasing power of the two countries, the real difference is even greater. Regarding the structure of the costs, direct costs accounted for more in the Belgian study than in ours (62% and 51%, respectively). The proportions of direct costs due to hospitalizations and outpatient care were similar (around 50% each) in the Belgian study, whereas in our study the costs of outpatient care (76%) were three times higher than those of hospitalizations (24%), which may reflect differences in patient pathways in the two countries’ health systems. Among outpatient costs, the costs of medication had essentially the same weight in the Belgian and Portuguese studies (56% and 55%, respectively).

Leal et al.22 reported costs from a societal perspective of cardiovascular disease in each country of the European Union (EU) for 2003. In this study, the total estimated cost for Portugal was €1.8 billion, less than in the present study, which focused only on atherosclerosis. In addition to methodological differences, the time interval between the two studies most likely contributed to these results. In the EU study, transportation costs (around €100 million in our study) were not considered but informal care (amounting to €392 million) was included, unlike in our study, which heightens the difference between the estimates. Even so, the distribution of total direct and indirect costs, direct and indirect, was similar in the two studies (55% and 45%, respectively, in both), although medication accounted for a considerably higher proportion of direct costs in the EU study (52% vs. 30% in the Portuguese study). It should also be noted that the per capita cost of cardiovascular disease, one of the main clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis, estimated by Leal et al. for Portugal using the purchasing power parity method, was €25, half of the mean figure for the EU (€50).

The costs of atherosclerosis in the USA can be found in the 2020 Update to the annual report published by the American Heart Association.23 This publication presents a summary of the epidemiology and costs associated with heart disease, stroke and cardiovascular risk factors. It does not provide data specifically on atherosclerosis but on the overall spectrum of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. The total estimated cost of cardiovascular disease and stroke in 2020 was US$351.3 billion (61% of which was direct costs and 39% indirect costs due to loss of future productivity resulting from premature cardiovascular disease and death by stroke).

Given the paucity of relevant studies and differences in methodology and time, the results of the present study are hard to compare with others analyzing the costs of illness in Portugal. Despite these difficulties, it should be noted that members of our group have estimated the cost of HF (€405 million in 2014),9 diabetes (€959 million in 2008),24 breast cancer (€309 million in 2014)25 and non-small cell lung cancer (€143 million in 2012)26 in Portugal. The relative costs of these conditions compared to that of atherosclerosis warrant the attention of the health authorities concerning the latter problem.

This study naturally presents various limitations, first and foremost related to the availability of national data. In the absence of a single source of information on which to base an estimate of the prevalence of atherosclerosis in Portugal, the authors had to rely on different sources, including the 2014 National Health Survey, the EPICA study, the study by Menezes et al., and the BDMH. The estimates derived from these sources were not always consistent, and so it was necessary in each case to select the source that we considered best represented the situation in the country. Aware of the risk of bias that such a selection could entail, we have aimed to explain the reasons for our choices when estimating the prevalence of each of the clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis. We also decided to adopt a conservative approach in all cases. For example, there are sources other than the National Health Survey that provide national data on IHD and stroke, particularly the VALSIM study, a national cross-sectional observational study that ran from 2006 to 2007 and included 719 general practitioners who assessed 16 856 patients. The study collected information on previous diagnoses of IHD (referred to as coronary disease) and stroke (without distinguishing between ischemic and hemorrhagic forms).27,28 The VALSIM study was older than the 2014 National Health Survey and also obtained higher prevalences of IHD and stroke (12% and 25% higher, respectively). In view of this, and notwithstanding the known limitations of self-reporting, we opted to use the 2014 National Health Survey as the main source of information on the prevalence of IHD (MI and chronic CAD) and stroke.

Given the systemic nature of the disease, it is not uncommon for more than one clinical manifestation of atherosclerosis to coexist in the same patient, and it was therefore necessary to adjust the overall prevalence to account for this overlap. Data from SIARS, particularly the clinical characteristics of patients with atherosclerosis treated in PHC in the ARSLVT, were used for this purpose. However, this could not be done in the specific case of chronic CAD, since the proportion of cases recorded in the database was lower than the national estimate based on the National Health Survey, and so we had to treat chronic CAD as independent of the other clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis. The assumption of independence is the method most often used in the literature, even for diseases in which independence of the probability of disease is clinically implausible.2

Furthermore, although real-life data were used for outpatient resource consumption in PHC, these may not be representative of the country as a whole, since we were able to consult the SIARS of only one of Portugal’s five Regional Health Administrations, that of Lisbon and Tagus Valley.

Another limitation of the study is the lack of a database of hospital outpatient information, particularly on care that does not generate DRG codes. This gap was filled by input from the expert panel. Although the members of the panel were varied intheir regional locations and medical specialties, their opinions may not fully represent nationwide clinical practice.

ConclusionThe results of this study demonstrate the importance of atherosclerosis at a national level. In terms of its economic impact in mainland Portugal, the cost of atherosclerosis represented 1% of gross national product and 11% of current health expenditure in 2016.

Conflict of interestThis study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Bayer Portugal, SA. Funding was independent of the study outcomes, which are the sole responsibility of the authors. A.A.S. received personal fees, grants and non-financial support for consulting services and lectures from Bayer Portugal, Ferrer and Bial. F.A. received personal fees and grants for consulting services, lectures and research from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bial, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Jaba Recordati and Merck Sharp & Dhome. D.C. received personal fees, grants and non-financial support for participating in scientific meetings from Bristol Myers Squibb, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck Serono, Ferrer, Pfizer, Novartis and Roche. C.G. received personal fees for consulting services and lectures from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer and Merck Sharp & Dhome. V.G. received personal fees, grants and non-financial support from Bayer, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, Novartis and Boehringer Ingelheim. A.M.S. received personal fees, grants and non-financial support for consulting services, lectures/scientific meetings participation and research from Amgen, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Jaba Recordati, Menarini, Mylan, Novartis and Tecnimede. L.M.P. received personal fees, grants and non-financial support for lectures from Bayer and Ferrer. J.M. received personal fees for consulting services and lectures from Bayer Portugal, AstraZeneca, Servier, Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dhome, Menarini and Amgen, as well as grants for scientific research from Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim and Ferrer. M.T.V. received personal fees for lectures from Tecnimede, Meda Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dhome, Bayer and Amgen. M.C. declares no conflicts of interest. J.C., J.A., R.A., M.F.C., F.L., A.V.C. and M.B. are members of the Evidence Based Medicine Center (CEMBE) at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon. This research center is devoted to pre‐ and postgraduate medical education and, since 2002, has undertaken several clinical, epidemiological and phamacoeconomic research projects, which received unrestricted funding from over 20 different pharmaceutical companies including Bayer Portugal SA. F.F. was a member of CEMBE at the time of this study. M.G. has taken part in several research projects that received unrestricted grants from pharmaceutical companies including Bayer Portugal SA. None of the authors is responsible for patents relevant for this work.

We are grateful to the ARSLVT for granting access to information that was essential to this study, especially data extracted from SIARS.

We would also like to thank the Central Administration of the National Health System (ACSS) for granting access to the BDMH.

Please cite this article as: Costa J, Alarcão J, Amaral-Silva A, Araújo F, Ascenção R, Caldeira D, et al. Os custos da aterosclerose em Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol. 2021;40:409–419.