There is a high prevalence of congenital heart disease (CHD) in Down syndrome (DS) patients. Children with DS and CHD also present greater susceptibility to pulmonary infections than those without CHD.

AimTo investigate the prevalence and types of CHD and their association with severe infections in children with DS in southern Brazil seen in a reference outpatient clinic.

MethodsChildren aged between six and 48 months with a diagnosis of DS were included consecutively in the period May 2001 to May 2012, and the presence of CHD and severe infections (pneumonia and sepsis) was investigated, classified and analyzed.

ResultsA total of 127 patients were included, of whom 89 (70.1%) had some type of CHD, 33 (37.7%) of them requiring surgical correction. Severe infections (pneumonia and sepsis) were seen in 23.6% and 5.5%, respectively. Of the cases of pneumonia, 70% had associated CHD (p=0.001) and of those with sepsis, 85% presented CHD (p=0.001).

ConclusionsOur study showed a high prevalence of CHD and its association with severe infections in children with DS seen in southern Brazil.

Defeitos cardíacos congênitos (DCC) têm alta prevalência em pacientes com síndrome de Down (SD). Além disso, crianças com SD que possuem DCC são mais suscetíveis às infecções pulmonares do que aqueles que não possuem cardiopatia.

ObjetivosInvestigar a prevalência, tipos de DCC e a sua associação com infecções graves em crianças com SD do sul do Brasil, atendidas em um ambulatório de referência.

MétodosDurante o período de maio de 2011 a maio de 2012, foram incluídas consecutivamente no estudo crianças entre 6‐48 meses de idade, diagnosticadas com SD nas quais foram investigadas, classificadas e analisadas as cardiopatias e infecções graves (sepse e pneumonia).

ResultadosForam incluídos no estudo 127 pacientes. Desses, 89 (70,1%) possuíam algum tipo de cardiopatia, sendo necessária a correção cirúrgica em 33 (37,7%) deles. Com relação à presença de infecções graves, pneumonia e sepse foram diagnosticadas respectivamente em 23,6 e 5,5% dos casos. Dentre os casos de pneumonia, 70% das crianças apresentavam cardiopatia (p = 0,001) e nos casos de sepse em 85% eram cardiopatas (p = 0,001).

ConclusõesO presente estudo demonstrou alta prevalência de diferentes formas de DCC e a sua associação com infecções graves em crianças com SD atendidas no sul do Brasil.

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common genetic cause of mental retardation worldwide, affecting 1/700 live births.1 Among the various findings related to DS, a constant concern is the high prevalence of congenital heart disease (CHD), reported to affect 40–60% of children born with DS, depending on the population studied.2–5 The most common is atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) (30–60%), followed by ventricular septal defect (VSD) (around 30%); others include ostium secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) (around 10%), patent ductus arteriosus (PAD) and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). Mitral valve prolapse may occur around the age of 20, with or without tricuspid valve prolapse and aortic regurgitation.6 CHD remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the neonatal period,7 due either to the heart defects themselves or to secondary factors, mainly associated with the compromised immune systems of these patients.8 Children with DS and CHD are more susceptible to pulmonary infections than those without CHD.9

Given that DS is the most common chromosomal anomaly among newborns, that the life expectancy of these patients has increased and that early diagnosis of CHD is of the utmost importance, the present study set out to investigate the prevalence and types of CHD and their association with severe infections in children with DS in southern Brazil seen in a reference outpatient clinic.

MethodsThe present study was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná (HC‐UFPR) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. It was performed in the DS outpatient clinic of HC‐UFPR in Curitiba, Paraná, during the period May 2011 to May 2012. Children aged between six and 48 months diagnosed with DS at birth based on clinical signs and confirmed by karyotype analysis were included consecutively. The investigation was based on a questionnaire completed by the family member accompanying the patient, together with review of the patient's medical records. Patients whose parents or guardians refused to participate were excluded from the study.

The CHD observed was classified according to Neonatologia – Pediatria Instituto da Criança HC/FMUSP 2011 using diagnostic methods in accordance with the recommended protocol (Avaliação cardiovascular do Neonato – Rev SOCERJ 2000). These included a detailed history, thorough physical examination, arterial blood gas analysis, chest X‐ray, echocardiography and electrocardiogram.

The severe infections analyzed in the study were sepsis and pneumonia, which were classified according to the Brazilian guidelines for treatment of severe sepsis.10 The information was recorded in a database, and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 statistical software.

ResultsA total of 127 patients were included in the study, median age 18 months (6–48 months; mean 20.7±14.6 months), 37.8% (48/127) female and 62.2% (79/127) male. Mean birth weight was 2759±620 g (1080–4470 g) and mean length was 46.1±3.27 cm (34.5–53 cm). Mean maternal age was 32.9±0.67 years (17–49), and 48% (61/127) were aged over 35 and 24.4% (31/127) were aged over 40.

In accordance with Vaz et al.,7 CHD was classified as follows: VSD, pulmonary atresia or stenosis, AVSD, TOF, ASD, coarctation of the aorta, and PDA. Of the 127 patients with DS, 89 (70.1%) had some form of CHD, of whom (52.8%) had more than one form (Table 1).

Prevalence of congenital heart disease in 127 children with Down syndrome.

| n | %a | Surgical repair (n=33/89) | |

| ASD | 51 | 40.1 | 21 (42.4%) |

| PDA | 30 | 23.6 | 9 (30.3%) |

| VSD | 23 | 18.1 | 11 (48.4%) |

| AVSD | 19 | 14.9 | 9 (45.4%) |

| TOF | 3 | 2.3 | 2 (66.6%) |

| PA/PS | 3 | 2.3 | 1 (33.9%) |

| CoAo | 1 | 0.7 | 1 (100%) |

Of the 89 children with CHD, 33 (37.7%) required surgical repair (median age at surgery 7 months, range 1–42 months). Of these, 51.5% (17/33) presented more than one form of CHD, the most common association being ASD and VSD, found in 24.2% (8/33). Three children (9.1%) had VSD only, while the remainder presented more severe disease, including TOF, AVSD and pulmonary atresia or stenosis (Table 1).

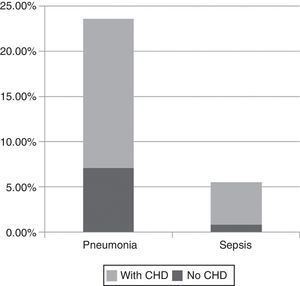

With regard to severe infections in the study population, pneumonia was diagnosed in 23.6% (30/127), predominantly male (2:1), with a mean age of 25.2 months, and sepsis was diagnosed in 5.5% (7/127) (mean age 19 months). Of the cases of pneumonia, 70% (21/30) had CHD (p=0.001), and in the case of sepsis, 85% (6/7) presented CHD (p=0.001) (Figure 1). All patients responded well to treatment and there were no deaths.

DiscussionThe present study showed a high prevalence of CHD (70.1%) in DS patients seen in a reference outpatient clinic in southern Brazil compared to the 41–56% in other populations in the literature.2–5 In the general population, CHD is found in 1/10 000 live births, distributed as follows: VSD 11.2%, pulmonary atresia or stenosis 5.4%, AVSD 3.3%, TOF 3.3%, ASD 3.2%, and PDA 0.9%. Vaz et al. reported AVDS in 43%, VSD in 32% and ASD in 10% of DS patients.7 In our study, the most common form of CHD was ASD (40.1%), followed by PDA (23.6%), VSD (18.1%) and AVSD (14.9%), with 52.8% presenting more than one form. The high prevalence of CHD in our study population may be partly due to advances in imaging techniques and greater awareness among radiologists of the association of DS and heart defects. The differences found in overall CHD prevalence compared to other DS populations may also be due to the lack of uniformity in classifying certain cardiac abnormalities, since in some studies PDA is not considered as CHD. Nevertheless, excluding cases of PDA from our analysis still gives a prevalence of 63.3%. With regard to types of CHD, in our study the prevalence of TOF was 3.2%, whereas others have reported 20% and 5.3%,11,12 and while AVSD was observed in 19.3% of our patients, other authors have found prevalences of 22.8–47%.2,12 The most common defect in a study by Vilas Boas et al. was also ASD, with a prevalence of 36.3%,13 while it was 55.0% in our study when the analysis included ASD both in isolation and associated with other defects.

In our study, patients with severe CHD more frequently required surgical repair, whereas those with less severe defects showed significant improvement with conservative treatment. Surgical repair was necessary in 37.3% (33/89). In the past such interventions always represented a high risk of mortality, but advances in surgical techniques, together with new devices and drugs, have improved postoperative survival rates, significantly increasing the life expectancy of children with DS and CHD. The median age of 7 months of our patients at the time of surgical repair shows that early detection and intervention reduces potential complications.14

With regard to maternal age, most mothers in our study were aged 31–40 at the time of the birth (mean age 32.9±0.76 years). It should be noted that 48% were aged over 35 and 24.4% were aged over 40, which confirms that older maternal age increases the likelihood of having a child with DS.15

Bacterial infections of the respiratory tract are a constant concern for those treating patients with DS, given that pneumonia is still a major cause of death at all ages in DS.16 In our study the prevalences of pneumonia and sepsis were 19.7% and 4.7%, respectively. Given the median age of our patients (18 months), these figures could be considered positive. Ribeiro et al.9 reported prevalences of 40% for pneumonia and 13% for sepsis among DS patients. The fact that the children in our study were followed in a reference outpatient clinic may have led to early identification and treatment of infections. Our study also showed a significant association between CHD and severe infections, particularly sepsis, five out of six cases being associated with CHD, and pneumonia (p=0.001), which is in agreement with previous studies and the clinical experience of pediatricians treating DS patients. Fortunately, despite the severity of the setting, all patients had a favorable course.

To summarize, our study showed a high prevalence of various forms of CHD and their association with severe infections in children with DS seen in southern Brazil.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Faria, PF, Nicolau JA, Melek M, et al. Associação entre cardiopatias congênitas e infecções graves em crianças com síndrome de Down. Rev Port Cardiol. 2014;33:15–18.