Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular disease in the elderly, affecting around 8.1% by the age of 85, with a negative impact on quality of life.

ObjectiveTo determine the impact of surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) on octogenarian quality of life in octogenarians.

MethodsIn a single-center retrospective study of octogenarians undergoing isolated SAVR for symptomatic AS between 2011 and 2015, quality of life was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) at baseline and at three, six and 12 months after surgery. Scores for the eight domains and two components of the SF-36 were compared at baseline and in the postoperative period by one-way analysis of variance.

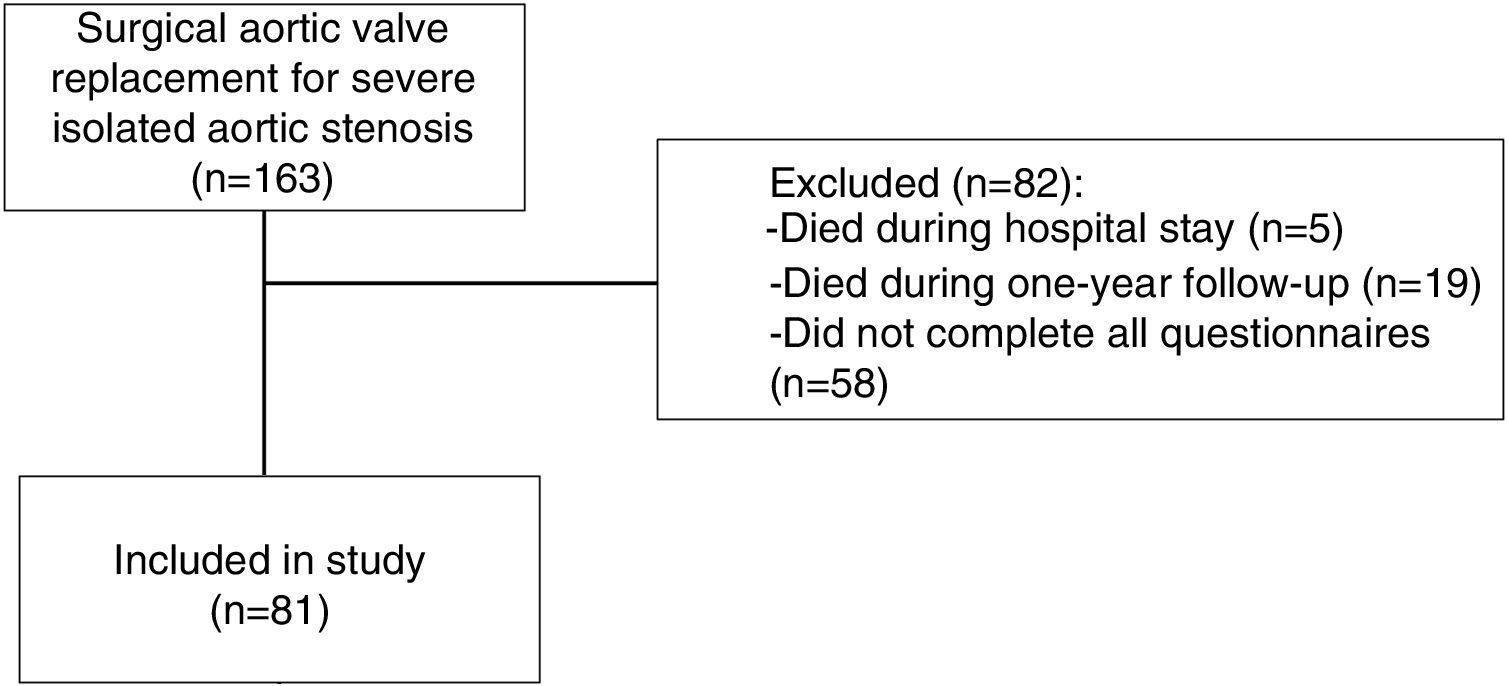

ResultsOver a five-year period, 163 octogenarians underwent SAVR, of whom 3.1% died in the hospital. Deceased patients and those who did not complete the SF-36 were excluded..

A total of 81 patients were included, mean age 83±2 years, 63% female, 60.5% in NYHA class II or higher and 19.7% with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. The mean logistic EuroSCORE was 10.7±5.1%. In the hospital, 1.2% suffered stroke, 1.2% received a permanent implantable pacemaker and 23.5% presented atrial fibrillation. In the assessment of quality of life, improvement was seen in all SF-36 domains (p<0.002) and in the physical component (p<0.001) at three, six and 12 months compared to baseline. The mental component also showed improvement, which was significant at six months (p=0.011).

ConclusionSAVR improved the physical and mental health status of octogenarians with severe AS. This improvement was evident at three months and consistent at six and 12 months.

A estenose aórtica (EA) é a doença valvular mais prevalente dos idosos e afeta 8.1% dos doentes com 85 anos, condicionando a qualidade de vida.

ObjetivoDeterminar o impacto da cirurgia de substituição valvular aórtica (SVA) na qualidade de vida dos octogenários.

MétodosEstudo unicêntrico e retrospetivo com octogenários submetidos a cirurgia de SVA por EA grave isolada entre 2011 e 2015. A qualidade de vida foi avaliada pelo questionário Short Form (SF)-36 no pré-operatório (PREOP), aos 3, 6 e 12 meses após cirurgia. As oito dimensões e as duas componentes do SF-36 foram comparadas no PREOP e no pós-operatório com a comparação múltipla anova one-way.

ResultadosNo período de cinco anos, 163 octogenários foram submetidos a cirurgia de SVA, 3,1% faleceram no internamento. Excluíram-se doentes falecidos e sem SF-36 preenchido. Foram incluídos 81 doentes com 83±2 anos, 63% mulheres, 60,5% em classe NYHA>2 e 19,7% com disfunção sistólica ventricular esquerda. O EuroSCORE logístico foi de 10,7±5,1%. No internamento, 1,2% tiveram acidente vascular cerebral, 1,2% implantaram pacemaker permanente e 23,5% apresentaram fibrilhação auricular. Na avaliação da qualidade de vida e na comparação com o PREOP: todas as dimensões do SF-36 (p<0,002) e a componente física (p<0,001) apresentaram melhoria aos 3, 6 e 12 meses. A componente mental apresentou melhoria, sendo esta significativa aos seis meses (p=0,011).

ConclusãoA cirurgia de SVA melhorou o estado de saúde físico e mental dos octogenários com EA, sendo essa melhoria evidente aos três meses e consistente aos 6 e 12 meses.

In recent decades, mean life expectancy has increased, leading to an increase in the number of elderly people with valvular disease.1 Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular disease in this patient group, affecting 8.1% by age 85.2 This is therefore an important patient group, but in a significant portion (30-40%)3,4 surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is still denied, leading to a dismal prognosis, with one-year mortality ranging between 30% and 50%.5,6 SAVR is thus the recommended treatment for symptomatic severe AS.7–9

Although octogenarians have more comorbidities and therefore higher surgical risk than younger patients, the evidence demonstrates that in some of these patients, the surgical risk may be acceptable to perform SAVR, with mortality reported to be between 1.9% and 9%.10–18

On the other hand, it should be pointed out that the main purpose of surgery in this age group is to improve quality of life rather than survival, given that the increase in longevity is marginal.19,20 Quality of life can be assessed using questionnaires such as the Medical Outcomes Study Questionnaire Short Form 36 (SF-36), a validated, credible and widely-used general health survey.18,21–24 However, there have been few studies on the impact of SAVR on octogenarians’ quality of life.18,25–27

ObjectiveTo determine the impact of SAVR for severe AS on the quality of life of octogenarians.

MethodsPatient selectionThis retrospective descriptive correlational study was performed in the cardiothoracic surgery department of Hospital Santa Marta, Lisbon.

Between January 2011 and December 2015, 163 consecutive patients aged 80 years or over with isolated severe AS underwent SAVR. Severe AS was defined in accordance with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on valvular disease.7

The criteria for acceptance of patients for surgery were technical feasibility and absence of cognitive dysfunction and frailty. The mean logistic EuroSCORE of the sample was 10.7%.

Quality of life was assessed using the SF-36 questionnaire, version 221 at four time points: at baseline and at three, six and 12 months after surgery.

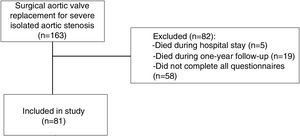

Patients who did not complete the SF-36 questionnaire at all of the above time points (n=58), and those who died during hospital stay (n=5) or during follow-up (n=19), were excluded. After application of the exclusion criteria, 81 patients who underwent SAVR for isolated severe AS were included (Figure 1).

Definition of variablesData were collected on demographics (age and gender), relevant history (heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease [CKD]) and cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity and smoking). Preoperative clinical data were assessed, including New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class28 and Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina class.29 Preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography and the logistic EuroSCORE was calculated.30

Creatinine clearance was estimated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula.31 CKD was defined as creatinine clearance <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and obesity as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2.

In-hospital mortality was defined as death occurring during hospitalization for surgery.

SF-36 Health SurveyThe SF-36 Health Survey is a widely used questionnaire developed under the aegis of the Medical Outcomes Study.21 The Portuguese version has been validated by Ferreira et al. for the Portuguese population.32

The questionnaire contains 36 health-related multiple-choice questions grouped into eight domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health). The eight domains are scored from 0 (worst health state) to 100 (best health state) and are summarized in two scales that measure the physical and mental components.21

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was carried out to characterize the population profile. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation and categorical variables are presented as percentage. In the quality of life assessment, the eight domains and two components of the SF-36 did not follow a normal distribution and so a non-parametric test was used. The domains and components were compared at four time points (preoperatively and at three, six and 12 months postoperatively) using one-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons. The level of significance was set at a p value of <0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0.

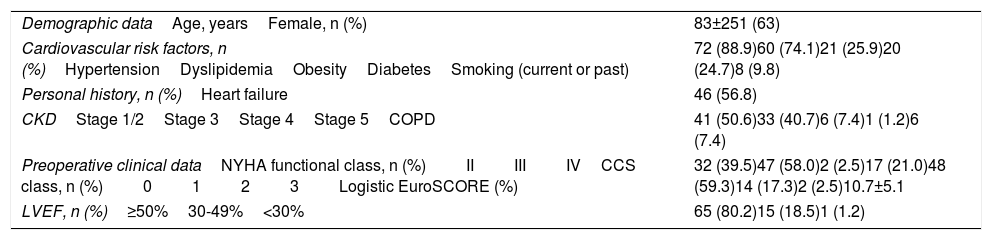

ResultsDemographic characteristicsThe demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population (n=81).

| Demographic dataAge, yearsFemale, n (%) | 83±251 (63) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%)HypertensionDyslipidemiaObesityDiabetesSmoking (current or past) | 72 (88.9)60 (74.1)21 (25.9)20 (24.7)8 (9.8) |

| Personal history, n (%)Heart failure | 46 (56.8) |

| CKDStage 1/2Stage 3Stage 4Stage 5COPD | 41 (50.6)33 (40.7)6 (7.4)1 (1.2)6 (7.4) |

| Preoperative clinical dataNYHA functional class, n (%)IIIIIIVCCS class, n (%)0123Logistic EuroSCORE (%) | 32 (39.5)47 (58.0)2 (2.5)17 (21.0)48 (59.3)14 (17.3)2 (2.5)10.7±5.1 |

| LVEF, n (%)≥50%30-49%<30% | 65 (80.2)15 (18.5)1 (1.2) |

CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina classification; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

The mean age of the 81 patients was 83±2 years and 63% were female. Regarding cardiovascular risk factors, 89% of the patients were hypertensive, 74% had dyslipidemia and 25% were diabetic. CKD stage 3 or higher was found in 49% of the patients. In the preoperative functional assessment, 61% of the patients were in NYHA class >2 and 20% in CCS class ≥2, while 20% had LVEF <50%. Mean logistic EuroSCORE was 10.7±5.1%.

Operative variablesAll patients underwent conventional sternotomy. The mean time of extracorporeal circulation was 92 min. Antegrade/retrograde cardioplegia was used in most cases (74 patients), followed by retrograde (six patients) and antegrade (one).

A biological valve was implanted in 80 patients. The median annulus diameter was 21 mm.

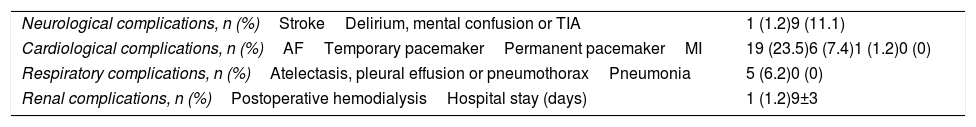

In-hospital complicationsMean hospital stay was 9±3 days.

With regard to neurological complications, 1.2% of the patients suffered stroke and 11.1% presented delirium, mental confusion or transient ischemic attack. In terms of cardiological complications, 23.5% of the patients presented atrial fibrillation and 1.2% had a permanent pacemaker implanted.

In-hospital complications in the study population are presented in Table 2.

In-hospital complications in the study population (n=81).

| Neurological complications, n (%)StrokeDelirium, mental confusion or TIA | 1 (1.2)9 (11.1) |

| Cardiological complications, n (%)AFTemporary pacemakerPermanent pacemakerMI | 19 (23.5)6 (7.4)1 (1.2)0 (0) |

| Respiratory complications, n (%)Atelectasis, pleural effusion or pneumothoraxPneumonia | 5 (6.2)0 (0) |

| Renal complications, n (%)Postoperative hemodialysisHospital stay (days) | 1 (1.2)9±3 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; MI: acute myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

During one-year follow-up, two patients (2.5%) suffered stroke, one (1.2%) had acute respiratory distress syndrome and two (2.5%) were hospitalized for unknown causes.

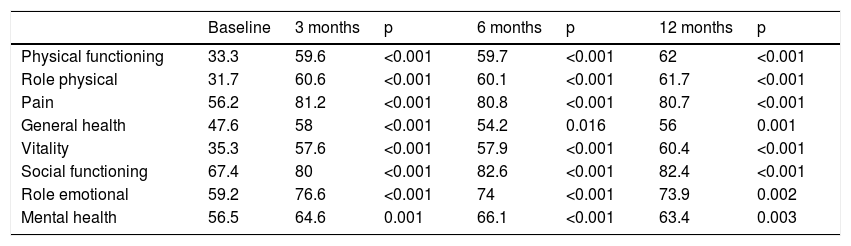

Assessment of quality of life using the SF-36 questionnaireThe results for the eight domains of the SF-36 questionnaire are presented in Table 3. All the domains showed statistically significant improvement (p<0.02) at three, six and 12 months compared with the preoperative period. Comparison between the three, six and 12-month postoperative periods showed no statistically significant differences.

Comparison of the score for the eight domains of the SF-36 at baseline compared with 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery.

| Baseline | 3 months | p | 6 months | p | 12 months | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 33.3 | 59.6 | <0.001 | 59.7 | <0.001 | 62 | <0.001 |

| Role physical | 31.7 | 60.6 | <0.001 | 60.1 | <0.001 | 61.7 | <0.001 |

| Pain | 56.2 | 81.2 | <0.001 | 80.8 | <0.001 | 80.7 | <0.001 |

| General health | 47.6 | 58 | <0.001 | 54.2 | 0.016 | 56 | 0.001 |

| Vitality | 35.3 | 57.6 | <0.001 | 57.9 | <0.001 | 60.4 | <0.001 |

| Social functioning | 67.4 | 80 | <0.001 | 82.6 | <0.001 | 82.4 | <0.001 |

| Role emotional | 59.2 | 76.6 | <0.001 | 74 | <0.001 | 73.9 | 0.002 |

| Mental health | 56.5 | 64.6 | 0.001 | 66.1 | <0.001 | 63.4 | 0.003 |

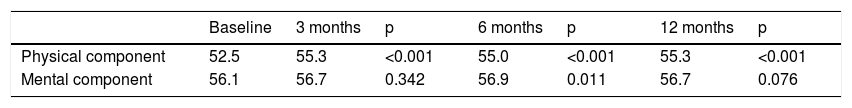

The results for the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire are shown in Table 4. The mental component presented a statistically significant improvement at six months compared with the preoperative period (p=0.011). At three (p=0.34) and 12 (p=0.076) months there was improvement, although this was not statistically significant.

The physical component showed statistically significant improvements (p<0.001) at three, six and 12 months compared with the preoperative period. However, no statistically significant differences were found when the three-, six- and 12-month postoperative periods were compared with each other.

DiscussionThis study aimed to assess the impact of SAVR during the first postoperative year on the quality of life of octogenarians with isolated severe AS. Surgical mortality and morbidity rates were also analyzed.

In this single-center series, SAVR improved quality of life in both physical and mental terms compared with the preoperative period, and morbidity and mortality rates were acceptable.

In-hospital mortality was 3.1%, comparable to other published series, which report rates between 1.9% and 9%.11–18

The mortality associated with SAVR in this age group has fallen in recent decades, from 7.5% in 1982-1999 to 5.8% in 2000-2006.33,34 These results are due to improvements in surgical techniques, anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, postoperative care and organ protection.12,35,36

As regards clinical complications, in our study 1.2% of patients suffered stroke, 1.2% had a permanent pacemaker implanted and 23.5% presented atrial fibrillation during hospitalization. The rates presented are similar to those in other series of octogenarians with severe AS, demonstrating that SAVR is feasible in this patient group.12,14,15

In our study, we used the SF-36 health survey21 to assess the quality of life at four time points: in the preoperative stage and at three, six and 12 months after surgery. A comparison with the preoperative period is essential in order to assess changes in quality of life. By contrast, some series assessed quality of life only in the postoperative period, which consequently affected their analysis and interpretation.23,24,37 To our knowledge, there are two studies in the literature that assessed quality of life with the SF-36 in the pre- and postoperative periods in octogenarians with severe AS.18,26 The reason we performed this assessment at three time points in the postoperative stage was to understand changes in quality of life over the first year. Given that in the first weeks after the intervention patients are in a worse clinical state due to the trauma of surgery, we decided that the first postoperative assessment would be at three months.

With regard to analysis of the eight SF-36 domains, our study revealed a statistically significant improvement in all domains (p<0.02) at the three postoperative time points compared to the preoperative period. It should be pointed out that the improvement in quality of life occurred early on, at three months. For example, between baseline and three months, there were increases of 28 points in the role physical domain (p<0.001), 26 points in the physical functioning domain (p<0.001), 20 points in the pain domain (p<0.001) and 17 points in the role emotional domain (p<0.001). Considering the morbidity associated with cardiothoracic surgery, one would expect this positive effect to have taken longer than three months to reach statistical significance, but this was not the case.

In a study of 20 octogenarians, Lam et al. found that improvement was observed at six months postoperatively in five of the eight SF-36 domains: bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning and mental health.26 Limitations of Lam et al.’s study included the small number of patients, analysis at only one postoperative time point, and failure to consider the components of the SF-36 individually.26

With regard to analysis of the SF-36 components, in our series the physical component presented significant improvement at all postoperative time points compared with baseline (p<0.001). These findings show that in spite of the patients’ advanced age (mean 83±2 years), surgery improved their physical capacity, and this was evident early on, at three months postoperatively. In 163 octogenarians who underwent SAVR for severe AS (isolated surgery in 88) assessed using the SF-36 at baseline, one month and 12 months, Klomp et al. identified improvement in the physical component at 12 months (p<0.001).18

As for assessment of the mental component, our study revealed improvement in the physical component at the three postoperative time points compared with baseline, which was significant at six months (p=0.011). In Klomp et al.’s series the mental component worsened at 30 days (p=0.002) and improved at 12 months compared with the preoperative period, although without statistical significance (p=0.1).18

Other studies have also demonstrated postoperative improvement in the quality of life of octogenarians undergoing SAVR, through the use of other health questionnaires such as the SF-12,38 Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire39 and the Karnofsky Performance Score.25,27 Reynolds et al.25 used the SF-12 questionnaire in 300 patients undergoing SAVR and observed statistically significant improvement in the mental and physical components at six and 12 months (p<0.05) compared with the preoperative period.

Our study assessed the quality of life of octogenarians with isolated severe AS who underwent SAVR. Assessment preoperatively and at three time points in the first year of follow-up (three, six and 12 months) of the eight domains and two components of the SF-36 enabled a detailed analysis of the patients’ quality of life.

In patients whose age is already that of mean life expectancy and for whom increased longevity is thus not the main purpose of SAVR, quality of life is crucial and should therefore be systematically assessed. Given this priority, prospective studies are required with larger study populations to evaluate the impact of surgical intervention on quality of life.

Although our study does not compare therapeutic alternatives for this patient group, the ESC guidelines recommend that in patients with severe AS and intermediate or high surgical risk (Society of Thoracic Surgeons score or EuroSCORE II ≥4% or logistic EuroSCORE ≥10%), the choice between SAVR and transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) should be made by the heart team, with preference for TAVI in elderly patients by transfemoral access.40 It is important to point out that the complications associated with TAVI should not be underestimated, as shown by rates of pacemaker implantation (8.5%41-25.9%),42 paravalvular leak (5.3%),42 stroke (3.8%)43 and atrial fibrillation (8.6%43-12.9%).42 In our study, patients presented lower rates of stroke (1.2%) and of pacemaker implantation (1.2%) and a higher rate of atrial fibrillation (23.5%).

According to the ESC guidelines, many of our patients would be indicated for TAVI, but given our results, with a low rate of complications and improvement in quality of life, surgery should be considered as the first option. The decision-making process should also take into account that SAVR is currently a less costly procedure than TAVI. However, the decision between the two strategies should be individualized and taken collectively by the heart team.

LimitationsThis was a retrospective, observational, single-center study and as such is subject to inherent bias. Other limitations are the small population sample, selection of the patients by the surgical center, and exclusion of a significant proportion of patients who did not complete the SF-36 questionnaire at all four time points.

ConclusionIn octogenarians with severe AS, SAVR may be performed with acceptable mortality and morbidity rates.

In our study, SAVR improved octogenarians’ quality of life in physical and mental terms. This was already evident at three months after surgery and consistent at six and 12 months compared with the preoperative period.

In this age group, surgery should be considered given the evidence of clinical improvement in these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bento D, Coelho P, Lopes J, Fragata J. A cirurgia de substituição valvular aórtica melhora a qualidade de vida dos octogenários com estenose aórtica severa. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:251–258.