In the July 2019 issue, Rosa et al. reported their single center experience of alcohol septal ablation (ASA) in 80 symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).1 The authors explained how successful ASA resulted in favorable clinical follow-up, defined as fewer cardiac death and lower hospitalization rates for cardiac cause. This editorial will contextualize the results based on our single center2 and multicenter3–7 experience.

The authors chose a weak primary endpoint (echocardiographic gradient reduction >50% after one year) to call ASA a successful procedure. Despite redo-ASA being performed in eight patients and myectomy in two patients, 11 patients had an unsuccessful procedure. This is surprising as peak creatine kinase after alcohol injection was comparable in both groups. When considering the reason for the high number of failures, it is noteworthy that the total number of patients with systolic anterior motion (SAM) as a typical finding in obstructive HCM with subaortic obstruction is low in the total study group (45%), and even lower in the group of patients with unsuccessful outcomes (18% vs. 50%). This raises questions about the mechanism of obstruction: did the authors treat a majority of patients without resting, but only provocable subaortic gradients, or patients with mid-ventricular gradients without SAM? Did they misdiagnose patients with a membrane causing fixed obstruction? These questions underline the importance of clear identification of the mechanism of obstruction as stated in the current ESC guidelines.8

Another important step in successful ASA without procedural complications is the identification of the optimal target branch. The first necessary step to avoid unwanted alcoholization=necrosis with e.g. potential risk of mitral or tricuspid regurgitation by involvement of papillary muscles is the use of contrast echocardiography and the choice of the optimal contrast agent. A very careful intraprocedural ultrasound with analysis from five different views (four/five-chamber apical, three-chamber apical, parasternal short and long axis and subcostal) is the keystone of successful ablation, which improves hemodynamic outcomes and reduces the number of complications.9 We found that after unavailability of the first choice Levovist™, cooled agitated Gelafundin 4%™ is superior to commercially available echocardiographic contrast agents.10 The agent used in this study produced the worst results with a risk of not identifying misplacements, resulting in failed hemodynamic success and potential necrosis in non-target areas.

The number of complications is related to the experience of the operators.4,7,11 Despite the relatively low number of procedures, the number of complications is low. One inferior infarction due to collateralization was the only avoidable complication. As we have pointed out,12 it is of utmost importance to exclude collaterals by use of maximal frame rate during the injection of radiographic contrast dye to exclude balloon leakage.

We should analyze the study in the context of large single and multicenter studies. Our own experience of long-term follow-up in 952 patients after alcohol ablation showed estimated 5-year survival was 95.8%, estimated 5-year cardiovascular event-free survival of 98.6%, and an estimated 5-year cardiac event-free survival of 98.9%. Corresponding values at 10 years were 88.3%, 96.5%, and 97.0%, and at 15 years 79.7%, 92.3%, and 96.5%. The main finding was that the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) was not increased after induction of a therapeutic infarction.2 Due to our careful examinations before alcohol injection we did not inject alcohol in another 62 patients - 6.1% of the total cohort of 1014 patients in whom ASA was intended. In this subgroup of patients, we avoided complications, as previously described, using careful contrast echography and excluding collaterals.

Many years ago a large European multicenter registry (EURO-ASA) was established. This group analyzed the influence of septal thickness on alcohol ablation results in alcohol ablation in obstructive HCM. Subgroup analyses of the registry showed comparable short-term results and long-term relief of dyspnea, residual left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction and occurrence of repeated septal reduction procedures in patients with basal interventricular septum (IVS) ≥30 mm and those with IVS <30 mm.5 However, long-term all-cause mortality and cardiac mortality were worse in the ≥30 mm group. Further analysis showed that patients with obstructive HCM and mild hypertrophy (IVS ≤16 mm) had a greater incidence of early post-ASA complications, such as a need for pacemaker implantation, but their long-term survival was better than in patients with IVS >16 mm. While relief of symptoms and reduction of LVOT obstruction were similar in both groups, the need for repeat septal reduction was higher in patients with IVS >16 mm.6 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that ASA was safe in younger patients in terms of long-term follow-up.3

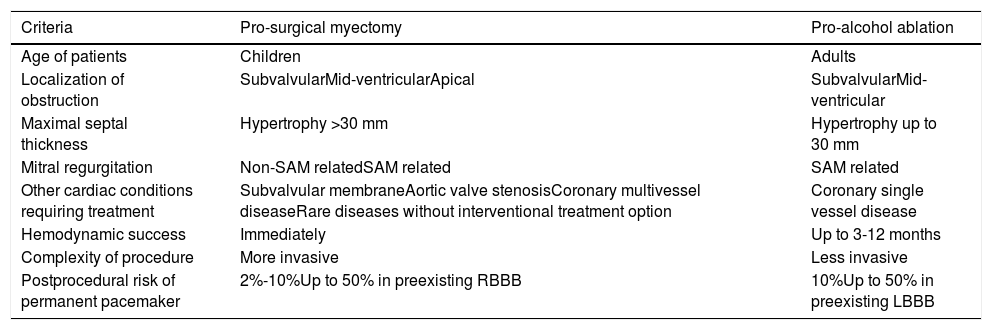

All the above mentioned studies revealed favorable long-term follow-up without an increased risk of SCD. Despite the lack of randomized trials, the morphologic criteria of obstructive HCM and experience of the operator (cardiac surgeon and/or interventional cardiologist) are the main criteria influencing the choice of optimal treatment for a symptomatic patient with obstructive HCM, as illustrated in Table 1. It should be underlined that specialized HCM centers appear to be the best choice above mentioned for optimal therapy for symptom relief and assessment of SCD risk.

Clinical and morphologic criteria influencing the type of optimal gradient reduction therapy in an individual with symptomatic obstructive HCM.

| Criteria | Pro-surgical myectomy | Pro-alcohol ablation |

|---|---|---|

| Age of patients | Children | Adults |

| Localization of obstruction | SubvalvularMid-ventricularApical | SubvalvularMid-ventricular |

| Maximal septal thickness | Hypertrophy >30 mm | Hypertrophy up to 30 mm |

| Mitral regurgitation | Non-SAM relatedSAM related | SAM related |

| Other cardiac conditions requiring treatment | Subvalvular membraneAortic valve stenosisCoronary multivessel diseaseRare diseases without interventional treatment option | Coronary single vessel disease |

| Hemodynamic success | Immediately | Up to 3-12 months |

| Complexity of procedure | More invasive | Less invasive |

| Postprocedural risk of permanent pacemaker | 2%-10%Up to 50% in preexisting RBBB | 10%Up to 50% in preexisting LBBB |

LBBB: left bundle branch block; RBBB: right bundle branch block; SAM: systolic anterior motion.