5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a first-line agent in several cancer therapy regimens. Cardiotoxicity is common, especially in patients with coronary artery disease. We report the case of an acute coronary syndrome presumably induced by 5-FU in a patient with previously unknown and asymptomatic corotabelnary artery disease and with an estimated intermediate risk for cardiovascular events. Pre-chemotherapy risk assessment and optimal patient care are still not standardized in this clinical scenario.

O 5-flurouracilo é um agente de primeira linha no tratamento de várias neoplasias. Associa-se frequentemente a toxicidade cardíaca, particularmente em doentes com doença coronária. O caso apresentado ilustra uma síndrome coronária aguda presumivelmente precipitada por 5-FU, num doente com doença coronária previamente assintomática e desconhecida e com risco estimado de eventos cardiovasculares de nível intermédio. A avaliação de risco pré-quimioterapia e a melhor abordagem para a prevenção e manejo desse cenário clínico permanecem por definir.

The fluoropyrimidines play an important part in cancer therapy, for which they are currently the third most used drug class.1,2 They include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), administered intravenously, and its orally administered prodrug capecitabine, which is subsequently metabolized to 5-FU. These drugs are antimetabolites that inhibit the action of thymidylate synthase, preventing the synthesis of nucleotides that are essential for cell survival, especially in cancer tissue.

The prevalence of 5-FU-associated cardiotoxicity is reported to be 1.4-4% of the overall population treated3,4 and 5-15% of those with known coronary artery disease (CAD).5,6 However, the incidence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) has been reported as 22-36% in smaller observational studies.1,7 Cardiotoxicity can manifest as ACS, angina, coronary dissection, cardiomyopathy, malignant arrhythmias or sudden death.8 Mortality from 5-FU-associated cardiotoxicity is significant, ranging from 2.2%9 to 18%,8 with higher rates in cases of re-exposure to the drug.

Risk assessment in patients eligible for treatment with 5-FU and subsequent patient care are still not standardized. We present the case of a patient who suffered an ACS after beginning 5-FU treatment.

Case reportWe report the case of a 60-year-old man, a former smoker (seven years’ abstinence), with hypertension and dyslipidemia. He had a history of colon adenocarcinoma seven years previously and had recently been diagnosed with advanced-stage adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. He was medicated with perindopril 5 mg daily, aspirin 100 mg daily and pitavastatin 2 mg daily as primary prevention, since there was no history of atherosclerotic disease in any vascular territory. Forty-eight hours before admission, he had begun a cycle of chemotherapy using the folinic acid, 5-FU and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) regimen. He was admitted with constricting retrosternal chest pain that began suddenly while at rest, radiating to the left arm and lasting more than 30 min. He reported no previous cardiovascular symptoms. At the time of admission he was still undergoing 5-FU infusion.

On initial observation the patient was without pain, with blood pressure 124/74 mmHg, heart rate 72 bpm and 95% oxygen saturation in room air. Physical examination was unremarkable.

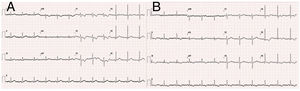

The electrocardiogram (ECG) performed in hospital triage (Figure 1) showed sinus rhythm with ST segment depression of <1 mm in V1-V3 and T-wave inversion. The ECG performed 60 min after admission revealed dynamic repolarization changes with T-wave inversion in V4-V6 and in DII, DIII and aVF (Figure 1).

Laboratory tests showed elevated high-sensitivity troponin T sampled one hour after symptom onset (16 ng/l; reference value 14 ng/l) compatible with ongoing ACS, and no other relevant findings.

The echocardiogram showed a non-dilated and non-hypertrophied left ventricle with preserved ejection fraction and no wall motion abnormalities, diastolic parameters within normal ranges and non-dilated right chambers, with normal right ventricular free wall longitudinal strain.

A diagnosis of acute non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction was assumed and antithrombotic therapy was begun. The 5-FU infusion was immediately suspended.

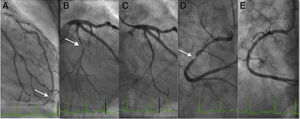

The patient remained in Killip class I, with peak troponin of 27 ng/l and GRACE score of 107. Invasive risk stratification by coronary angiography (Figure 2) was performed 36 hours after symptom onset, which showed a very distal focal 80% lesion in the left anterior descending artery, 70% lesions in the first and second diagonals, a 90% stenosis in the distal circumflex artery, and diffuse disease of the proximal and mid right coronary artery with a 90% stenosis in the mid segment. Angioplasty of the right coronary and circumflex arteries was performed and XIENCE® 3.0×38 mm and Synergy® 2.24×20 mm drug-eluting stents, respectively, were implanted, with a good final angiographic result.

DiscussionThis case report presents an ACS apparently triggered by 5-FU in a patient with previously unknown CAD. Although cardiotoxicity secondary to 5-FU is relatively well documented,7 there are several unanswered questions relating to pre-chemotherapy risk assessment and the optimal therapeutic strategy to adopt following a cardiotoxic event. As stated above, estimates of the incidence of ischemic events associated with 5-FU range from 1.4% to 36%, reflecting the heterogeneity of these studies. Existing heart disease is associated with more severe events,9 a finding that is common to all the studies published on this subject.

The pathophysiological mechanisms behind ACS associated with 5-FU are not fully understood. The most commonly accepted hypothesis is that endothelial injury induced by 5-FU decreases nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation, destabilizing atherosclerotic plaque with in-situ thrombus.8,11 Besides infarction, electrocardiographic alterations suggestive of silent ischemia are observed in 68% of patients followed prospectively.10 The clinical significance of these alterations is unclear; they may reflect changes in coronary flow and predict clinical events.12 The mode of the drug's administration affects the incidence of cardiotoxicity, the risk being higher with administration by infusion (7.6-18%) than by bolus (1.6-3%).3,5 Although there are more data on cardiotoxicity under 5-FU than under capecitabine, studies have reported that the level of risk is similar for both drugs.1,6

Conventional cardiovascular risk factors are more often found in patients who suffer an acute ischemic event associated with 5-FU.3 On the basis of his known risk factors, the patient in the case presented had an intermediate risk for cardiovascular events as estimated by a Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation (SCORE)13 of 3 on admission, and his pre-existing CAD was only discovered subsequently. The fact that the patient was completely asymptomatic prior to the acute event, and the time relation between symptom onset and mode of 5-FU administration, suggest the existence of a causal relationship.

Pre-chemotherapy screening for CAD in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, although logical, is neither mandatory nor standardized. Non-invasive anatomical assessment, such as by calculation of the Agatston score or cardiac computed tomography angiography, may be useful in patients eligible for 5-FU therapy by identifying those at greater risk for coronary events if exposed to the drug.

The reported incidence of ischemic events in patients treated with 5-FU is up to 36%, especially in those with CAD, and so the risk of such events should not be underestimated. These patients should be closely monitored for symptoms and may undergo continuous electrocardiographic monitoring to detect silent ischemia,10 which if confirmed may justify suspension of 5-FU therapy. The occurrence of symptoms should prompt a comprehensive assessment including ECG, biomarkers of myocardial necrosis, non-invasive ischemia testing and possibly coronary angiography.

Following diagnosis of an ACS, it is essential to stop 5-FU therapy. Recurrence after reintroduction of the drug is seen in 82-100% of cases,8 and mortality following reintroduction is also higher, with rates of around 18% reported.7 As the main mechanism is vasospasm, calcium channel blockers and nitrates are the preferred drugs and have been shown to be effective in observational studies.8 However, vasodilators are ineffective in preventing coronary vasospasm after the reintroduction of 5-FU,5 and their role in primary prevention is not well established. Treatment of ACS in this context is in other respects standard, although the impact of dual antiplatelet therapy on cancer management, as well as potential drug interactions, should be borne in mind.

It is essential for cardiologists and oncologists to work closely together to decide on the safest and most effective therapeutic strategy. Decisions on cancer therapy are always complex, depending on the stage of the tumor and the patient's clinical characteristics, and discontinuing 5-FU is bound to make it more difficult to define an appropriate therapeutic plan. Capecitabine is also contraindicated after an ischemic event due to cross-reactions between drugs.11 Therapeutic regimens without fluoropyrimidines have been described, although they may not be as effective. Deboever et al. published an interesting review of alternatives to fluoropyrimidines in patients with documented cardiotoxicity.2

Conclusion5-FU-associated cardiotoxicity is common, frequently manifesting as ACS or silent ischemia, especially in patients with documented CAD. It is thus important to standardize the assessment, monitoring and treatment of these patients. In those with cardiovascular risk factors, non-invasive screening for CAD, such as by calculation of the Agatston score or cardiac computed tomography angiography, may help improve patient selection, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality in this clinical scenario.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Félix-Oliveira A, Vale N, Madeira S, Mendes M. Síndrome coronária aguda em doente oncológico: um problema evitável?. Rev Port Cardiol. 2018;37:791.