After several decades of initiatives at international and national level inspired by the World Health Organization, tobacco consumption is still the second leading cause of death in the world and the leading cause of premature death and disability, as a result of various types of cancer and pulmonary, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease.

Tobacco consumption is also an important public health issue in Portuguese-speaking countries, which fully justifies the launch and implementation of these 2019 recommendations for reducing tobacco consumption in Portuguese-speaking countries by the Federation of Portuguese Language Cardiology Societies.

This position statement reviews recent changes in and the present epidemiology of tobacco consumption in the Portuguese-speaking countries, discusses the negative health impact of new forms of tobacco consumption, and addresses available prevention and drug treatment strategies.

Eliminating smoking requires a coordinated effort between various national and international bodies, with a policy approach in each country focusing on laws, education campaigns for primary prevention aimed at to the general public, particularly to encourage young people not to start smoking, and a health system approach to help smokers quit smoking permanently by a combination of drug treatment and cognitive behavioral therapy. The aim is to control the only cardiovascular risk factor that can be completely eliminated.

This position statement aims to alert health professionals to the need to approach the subject of smoking cessation with patients and their families during hospitalizations and outpatient consultations, and to provide them with up-to-date knowledge on how to quit smoking and maintain control of this risk factor in the long term.

Após várias décadas de iniciativas orientadas pela Organização Mundial de Saúde com expressão a nível global e nos diferentes países, o consumo de tabaco continua a ser a segunda causa de mortalidade no mundo e a primeira causa de morte prematura e de incapacidade em consequência de várias neoplasias, doenças pulmonares e cérebro-cardiovasculares, com ele relacionadas.

O consumo de tabaco, nos países de língua Portuguesa continua a ser também um problema importante de Saúde Pública, o que justifica plenamente o lançamento e a implementação destas «Recomendações de 2019 para a Redução do Consumo de Tabaco nos Países de Língua Portuguesa» pela Federação das Sociedades de Cardiologia de Língua Portuguesa.

Neste artigo de tomada de posição são revistas as últimas alterações recentes e a epidemiologia atual referente ao consumo de tabaco nos diferentes países de língua portuguesa, salientado o impacto negativo para a Saúde das novas formas de consumo de tabaco e abordadas as estratégias de prevenção e as terapêuticas disponíveis.

Banir o tabagismo exige um esforço concertado de várias entidades a nível nacional e internacional, incluindo uma abordagem política a nível de cada país baseada em leis específicas, em campanhas de educação orientadas para o público em geral, dirigidas nomeadamente para as novas gerações com o objetivo de não iniciarem o consumo de tabaco, associada a uma resposta do Sistema de Saúde com o objetivo de apoiar os fumadores a cessarem e a manterem-se livres do hábito de fumar no longo prazo, com recurso a uma associação de terapêutica farmacológica e de uma abordagem cognitivo-comportamental, com o intuito de obter o controlo do único fator de risco que pode ser totalmente abolido.

Esta tomada de posição da FSCLP chama a atenção para a necessidade de os profissionais de Saúde abordarem a problemática da cessação tabágica, junto dos doentes e dos seus familiares durante momentos-chave como os episódios de internamento hospitalar ou de consulta externa, e capacita-os com o conhecimento científico hoje existente para cessar o hábito e manter o controlo deste fator de risco a longo prazo.

Depending on the observer's epidemiological perspective and concept of causality, tobacco consumption can be considered the second leading cause of death attributable to classic cardiovascular risk factors worldwide, exceeded only by hypertension, and the leading cause of premature death and disability. When taken as an immediate cause, without contextualization in the complex processes that determine and maintain population behavior, in 2017 smoking was responsible globally for about 7.10 (6.83-7.37) million deaths and 182 (173-193) million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). Although the number of daily smokers (individuals aged 15 years and older who smoke every day) has decreased, the total number of smokers continues to rise, posing a major global challenge for healthcare systems.1

Physicians, who generally deal directly with individual patients, tend to consider health and illness to be limited to the patient's organ compromise and personal history, and are less appreciative of the ‘causes of the causes’ and the psychosocial determinants of phenomena and behaviors, which are inseparable from the ecological context and from economic interests. Environmental pollution (which is also worsened by smoking) is progressively increasing and is currently considered to be the most important cause of morbidity and mortality in the world,2 extending beyond the traditionally accepted risk factors. This fact is important for an understanding of the resistance to smoking control and for planning effective strategies to deal with the issue.

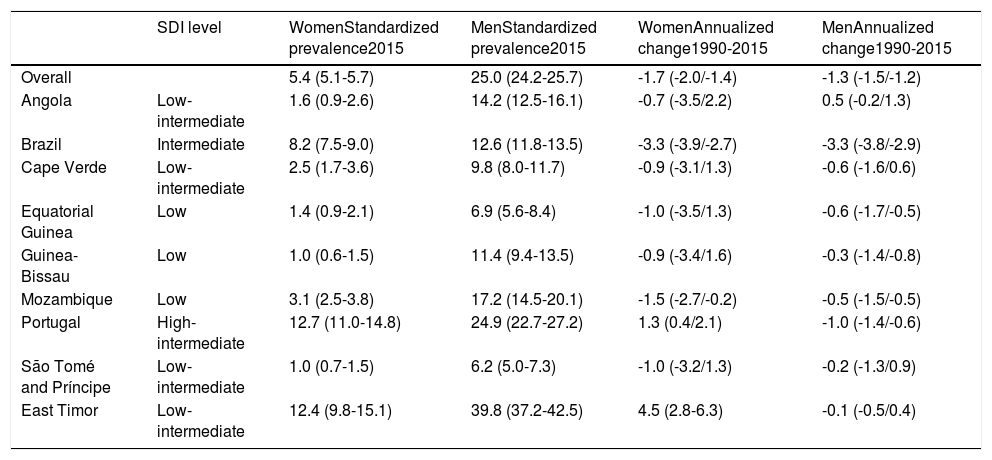

In all Portuguese-speaking countries (PSCs), smoking is more prevalent among men. The difference in rates between men and women varies between countries and is greater in the African countries. Table 1 shows the standardized prevalence by gender in 2015 and the annualized changes for men and women from 1990 to 2015 according to the sociodemographic index (SDI), the weighted geometric mean of per capita income, level of schooling and total fertility rate.3 The proportion of daily smokers in the PSCs is 19.0%, 16.8%, and 7.2% in African countries, Portugal, and Brazil, respectively.4

Standardized prevalence by gender in 2015, and annualized difference by gender from 1990 to 2015, according to the sociodemographic index.

| SDI level | WomenStandardized prevalence2015 | MenStandardized prevalence2015 | WomenAnnualized change1990-2015 | MenAnnualized change1990-2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 5.4 (5.1-5.7) | 25.0 (24.2-25.7) | -1.7 (-2.0/-1.4) | -1.3 (-1.5/-1.2) | |

| Angola | Low-intermediate | 1.6 (0.9-2.6) | 14.2 (12.5-16.1) | -0.7 (-3.5/2.2) | 0.5 (-0.2/1.3) |

| Brazil | Intermediate | 8.2 (7.5-9.0) | 12.6 (11.8-13.5) | -3.3 (-3.9/-2.7) | -3.3 (-3.8/-2.9) |

| Cape Verde | Low-intermediate | 2.5 (1.7-3.6) | 9.8 (8.0-11.7) | -0.9 (-3.1/1.3) | -0.6 (-1.6/0.6) |

| Equatorial Guinea | Low | 1.4 (0.9-2.1) | 6.9 (5.6-8.4) | -1.0 (-3.5/1.3) | -0.6 (-1.7/-0.5) |

| Guinea-Bissau | Low | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | 11.4 (9.4-13.5) | -0.9 (-3.4/1.6) | -0.3 (-1.4/-0.8) |

| Mozambique | Low | 3.1 (2.5-3.8) | 17.2 (14.5-20.1) | -1.5 (-2.7/-0.2) | -0.5 (-1.5/-0.5) |

| Portugal | High-intermediate | 12.7 (11.0-14.8) | 24.9 (22.7-27.2) | 1.3 (0.4/2.1) | -1.0 (-1.4/-0.6) |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Low-intermediate | 1.0 (0.7-1.5) | 6.2 (5.0-7.3) | -1.0 (-3.2/1.3) | -0.2 (-1.3/0.9) |

| East Timor | Low-intermediate | 12.4 (9.8-15.1) | 39.8 (37.2-42.5) | 4.5 (2.8-6.3) | -0.1 (-0.5/0.4) |

SDI: sociodemographic index.

Data from the Portuguese National Health Surveys (INS) (1987, 1995/96, 1998/99, 2005/06, and 2014) show that the prevalence of daily smokers in mainland Portugal decreased among men from 35.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 34.2-36.2%) in 1987 to 26.7% (95% CI 25.2-28.3%) in 2014, and increased in women from 6.0% (95% CI 5.6-6.4%) in 1987 to 14.6% (95% CI 13.6-15.8%) in 2014, with a higher prevalence in men from more disadvantaged socioeconomic groups and the opposite in women.5

The reported prevalence of smoking in Mozambique in 2003 was 39.9% in men and 18.0% in women.6 In a 2005 sample from the same country, the prevalence of daily tobacco use (including users of chewing tobacco, snuff, manufactured cigarettes, and hand-rolled cigarettes) had fallen to 33.6% in men and 7.4% in women, with different prevalence rates by gender and regions of the country.7

Brazil is the leading country among the PSCs in the control of smoking, with the third largest decline in the prevalence of daily smokers since 1990: 57% and 56% for men and women, respectively. This was achieved through a robust public policy, in which advertisements highlighting the harm to health caused by smoking were associated with restrictions on consumption and tax increases on tobacco products, among other measures.8

These measures stemmed from adherence to the recommendations by the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC),9 which include banning of terms such as ultra-light, light, low tar, mild, or any other term implying that such products are less harmful. The PSCs have joined the FCTC at different times, as discussed below in the section on legislation.

The percentage of deaths attributed to tobacco use across 195 countries increased from 7.28 (7.01-7.56) million in 2007 to 8.10 (7.79-8.42) million in 2017, an increase of 11.3% (9.1-13.4%), according to the Global Burden of Disease study.1 The same was seen with DALYs, from 200000 (188000-212000) in 2007 to 213000 (201000-227000) in 2017, an increase of 6.8% (4.6-9.0%). A similar trend was observed with regard to ischemic heart disease, from 1.50 (1.44-1.57) million deaths in 2007 to 1.62 (1.54-1.69) million in 2017, a 7.8% increase (4.6-11.1%), while DALYs increased from 38.4 (36.8-40.2) in 2007 to 40.6 (38.7-42.5) million in 2017, an increase of 5.6% (2.4-9.0%). Similar increases were observed in relation to deaths due to ischemic stroke, from 295000 (276000-317000) in 2007 to 335000 (313000-361000) in 2017, an increase of 13.4% (8.6-17.8%), with an increase in DALYs from 7.54 (69.1-8.26) million in 2007 to 90.0 (81.7-99.2) million in 2017, an increase of 19.3% (14.7-23.8%).1

It is important to note that approximately 80% of smokers live in low- and middle-income countries,10 which includes most of the populations of the PSCs, where the decline in tobacco consumption seen in high-income countries has not been observed.4 There is strong evidence that treating smoking in primary care is both opportune and cost-effective because of the wide coverage and the close long-term relationship between physician and patient in primary healthcare.11

Of the traditional risk factors considered in clinical practice for prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD), smoking is the only one that could be completely eliminated, although if the range of risk factors is broadened to include ecological and behavioral changes due to human activity, there are many other factors that could also be controlled.

In a social environment filled with stresses and frustrations, many of them driven by inequality and conflict, and constantly subjected to advertising, the consumption of psychoactive substances like tobacco and alcohol is habit-forming due to their effects on the reward circuit of the limbic system, leading to physical and psychological dependence. This system is the result of evolutionary adaptations to preserve the species, but it is also one of the causes of the repeated relapses observed when an individual tries to quit an addictive habit.12

Quitting smoking is, obviously, the most effective way to prevent tobacco-related diseases. However, insufficient efforts are made to take advantage of medical consultations, both outpatient and inpatient, to help patients begin the process of quitting smoking, which is the most frequent preventable cause of CVD and many cancers.11 The objective of this article is to provide an instrument to be used by healthcare professionals in their daily practice in the fight against smoking.

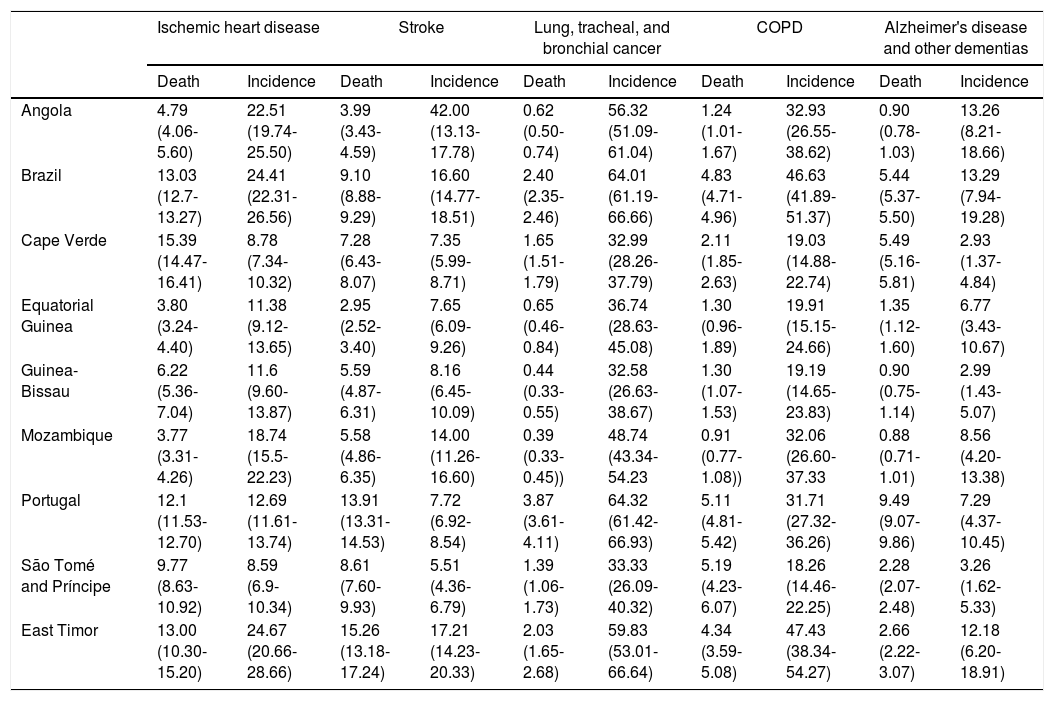

Epidemiology and pathophysiological mechanismsTable 2 shows the smoking-attributable risk for some diseases in the PSCs, presented as percentages of mortality and disease incidence. When smokers and never-smokers are compared, the risk of smokers is 2-3 times higher for stroke, ischemic heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease; 23 and 13 times higher for cancer in men and women, respectively; and 12-13 times higher for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Smokers also have a 2.87-fold higher risk of death from myocardial infarction compared with non-smokers.3

Smoking-attributable risk for certain diseases in Portuguese-speaking countries in 2017.3

| Ischemic heart disease | Stroke | Lung, tracheal, and bronchial cancer | COPD | Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Incidence | Death | Incidence | Death | Incidence | Death | Incidence | Death | Incidence | |

| Angola | 4.79 (4.06-5.60) | 22.51 (19.74-25.50) | 3.99 (3.43-4.59) | 42.00 (13.13-17.78) | 0.62 (0.50-0.74) | 56.32 (51.09-61.04) | 1.24 (1.01-1.67) | 32.93 (26.55-38.62) | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) | 13.26 (8.21-18.66) |

| Brazil | 13.03 (12.7-13.27) | 24.41 (22.31-26.56) | 9.10 (8.88-9.29) | 16.60 (14.77-18.51) | 2.40 (2.35-2.46) | 64.01 (61.19-66.66) | 4.83 (4.71-4.96) | 46.63 (41.89-51.37) | 5.44 (5.37-5.50) | 13.29 (7.94-19.28) |

| Cape Verde | 15.39 (14.47-16.41) | 8.78 (7.34-10.32) | 7.28 (6.43-8.07) | 7.35 (5.99-8.71) | 1.65 (1.51-1.79) | 32.99 (28.26-37.79) | 2.11 (1.85-2.63) | 19.03 (14.88-22.74) | 5.49 (5.16-5.81) | 2.93 (1.37-4.84) |

| Equatorial Guinea | 3.80 (3.24-4.40) | 11.38 (9.12-13.65) | 2.95 (2.52-3.40) | 7.65 (6.09-9.26) | 0.65 (0.46-0.84) | 36.74 (28.63-45.08) | 1.30 (0.96-1.89) | 19.91 (15.15-24.66) | 1.35 (1.12-1.60) | 6.77 (3.43- 10.67) |

| Guinea-Bissau | 6.22 (5.36-7.04) | 11.6 (9.60-13.87) | 5.59 (4.87-6.31) | 8.16 (6.45-10.09) | 0.44 (0.33-0.55) | 32.58 (26.63-38.67) | 1.30 (1.07-1.53) | 19.19 (14.65-23.83) | 0.90 (0.75-1.14) | 2.99 (1.43-5.07) |

| Mozambique | 3.77 (3.31-4.26) | 18.74 (15.5-22.23) | 5.58 (4.86-6.35) | 14.00 (11.26-16.60) | 0.39 (0.33-0.45)) | 48.74 (43.34-54.23 | 0.91 (0.77-1.08)) | 32.06 (26.60-37.33 | 0.88 (0.71-1.01) | 8.56 (4.20-13.38) |

| Portugal | 12.1 (11.53-12.70) | 12.69 (11.61-13.74) | 13.91 (13.31-14.53) | 7.72 (6.92-8.54) | 3.87 (3.61-4.11) | 64.32 (61.42-66.93) | 5.11 (4.81-5.42) | 31.71 (27.32-36.26) | 9.49 (9.07-9.86) | 7.29 (4.37-10.45) |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 9.77 (8.63-10.92) | 8.59 (6.9-10.34) | 8.61 (7.60-9.93) | 5.51 (4.36-6.79) | 1.39 (1.06-1.73) | 33.33 (26.09-40.32) | 5.19 (4.23-6.07) | 18.26 (14.46-22.25) | 2.28 (2.07-2.48) | 3.26 (1.62-5.33) |

| East Timor | 13.00 (10.30-15.20) | 24.67 (20.66-28.66) | 15.26 (13.18-17.24) | 17.21 (14.23-20.33) | 2.03 (1.65-2.68) | 59.83 (53.01-66.64) | 4.34 (3.59-5.08) | 47.43 (38.34-54.27) | 2.66 (2.22-3.07) | 12.18 (6.20-18.91) |

Values are expressed as % (95% confidence interval).

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Smoking is also associated with increased blood pressure and associated complications including death and impaired renal function, and with abdominal aortic aneurysms, which have an increased risk attributable to smoking, as well as higher aneurysm growth rate in smokers compared to non-smokers. Smoking is associated with cardiac rhythm disorders including atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia, and with a higher risk of heart failure and associated morbidity and mortality.13,14

The main tobacco-related diseases are coronary disease and myocardial infarction (25% higher incidence in smokers); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (85%); lung cancer (90%); cancer of the mouth, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, kidney, bladder, cervix, and breast (30%); and cerebrovascular disease (25%).

The risk of ischemic heart disease and associated mortality increases with number of years of smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day, and is seen at all levels of consumption, even fewer than five cigarettes per day and passive smoking. Patients who stop smoking after coronary artery bypass surgery have a lower risk of hospitalization for heart disease. Smoking cessation is the only effective way to prevent progression of thromboangiitis obliterans, improving symptoms and reducing the lifelong risk of amputation.15,16

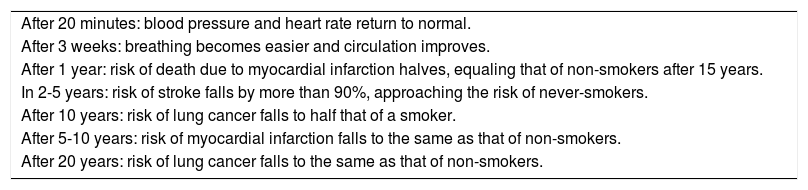

Smoking cessation has various benefits that should be pointed out to smokers during consultations (Table 3). Cigarette smoke contains more than 7000 chemical substances, many of which are toxic, and contributes to CVD in different ways, including adverse hemodynamic effects like increased blood pressure and heart rate, imbalance between oxygen supply and consumption, changes in coronary blood flow, endothelial dysfunction and damage, hypercoagulability and thrombosis, chronic inflammation, and lipid abnormalities, in addition to acting as a substrate for arrhythmias and cardiovascular events. These effects can be observed even in passive smokers.13,17

Short-, medium- and long-term benefits of smoking cessation (adapted from 18).

| After 20 minutes: blood pressure and heart rate return to normal. |

| After 3 weeks: breathing becomes easier and circulation improves. |

| After 1 year: risk of death due to myocardial infarction halves, equaling that of non-smokers after 15 years. |

| In 2-5 years: risk of stroke falls by more than 90%, approaching the risk of never-smokers. |

| After 10 years: risk of lung cancer falls to half that of a smoker. |

| After 5-10 years: risk of myocardial infarction falls to the same as that of non-smokers. |

| After 20 years: risk of lung cancer falls to the same as that of non-smokers. |

Smoking should be considered a chronic disease that can begin in childhood and adolescence, since about 80% of those who try tobacco do so while less than 18 years old. There is also a direct relationship between starting to smoke in childhood and continuing to smoke in adulthood. Primordial prevention, ensuring that children and adolescents do not start smoking in the first place, is an essential step in smoking control. Within a year or so of starting to smoke, children inhale the same amount of nicotine per cigarette as adults and experience the same craving for cigarettes and nicotine withdrawal symptoms, which usually develop very quickly at younger ages. One way to approach primordial prevention is by age groups, observing five main items (the “5 ‘A's”) for each group: Ask individuals about their tobacco use; Advise every smoker to quit; Assess the individual's motivation to quit and symptoms of dependence; Assist those attempting to quit smoking through counseling or therapy; and Arrange follow-up contact.19–21

In 2008 the WHO launched its MPOWER initiative,21 which has had proven impact on reducing the consumption of tobacco products. The abbreviation MPOWER is derived from the following measures: Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies; Protect people from tobacco smoke; Offer help to quit tobacco use; Warn about the dangers of tobacco; Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; Raise taxes on tobacco.

These measures have an impact on smoking cessation at the population level, but most smokers require individualized treatment from healthcare professionals, often combining a behavioral approach with medications, to quit smoking altogether.

New forms of tobacco useNew forms of tobacco use have emerged in the last 15 years that are promoted as carrying lower or no risk. Among these are electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), which work by vaporizing nicotine, flavors, and other ingredients in liquid form (e-liquid) that are inhaled by the user (vaping). The most popular brand among young people in the USA is Juul, in which the e-liquid is provided in small replaceable cartridges called pod mods. These devices, now in their third generation, deliver nicotine together with vaporizing and flavoring substances. Their effects are still largely unknown but could potentially carry health risks.13,14

Against the background of sophisticated marketing campaigns promoting such new forms of tobacco use, there are currently intense discussions in both society in general and the medical community about the potential risk of e-cigarettes as a cause of CVD and cancer. Although the available epidemiological evidence is not extensive and the risk of these new forms of smoking appears to be lower than that of the classic form of smoking, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that in the short term, they can cause endothelial dysfunction, DNA damage, oxidative stress, and temporary increases in heart rate. Long-term use appears to increase the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and mouth and esophageal cancer.3,13

Based on the ostensibly lower risk of e-cigarettes, they have been promoted as a way to quit smoking, but evidence is lacking for this claim. In 60% of cases, individuals smoke both regular tobacco cigarettes and e-cigarettes, which does not reduce the high risk of the former. In many cases, people use these new forms of smoking for a short time, after which they go back to the same level of smoking as before.13,14

Additionally, there are concerns among the medical community that e-cigarettes will cause young people to become addicted to nicotine, acting as a gateway to regular tobacco smoking.

Although it should be acknowledged that the currently available evidence is not robust, we recommend that people should quit all forms of tobacco use, or better still not start, including oral tobacco (chewing tobacco, snus, snuff, and dissolvable tobacco), vaping (e-cigarettes), cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, pipes, or hookahs. It is also important to combat secondhand tobacco smoke, as it carries similar risks to smoking itself, non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke having a 25-30% increased risk of CVD.13,14

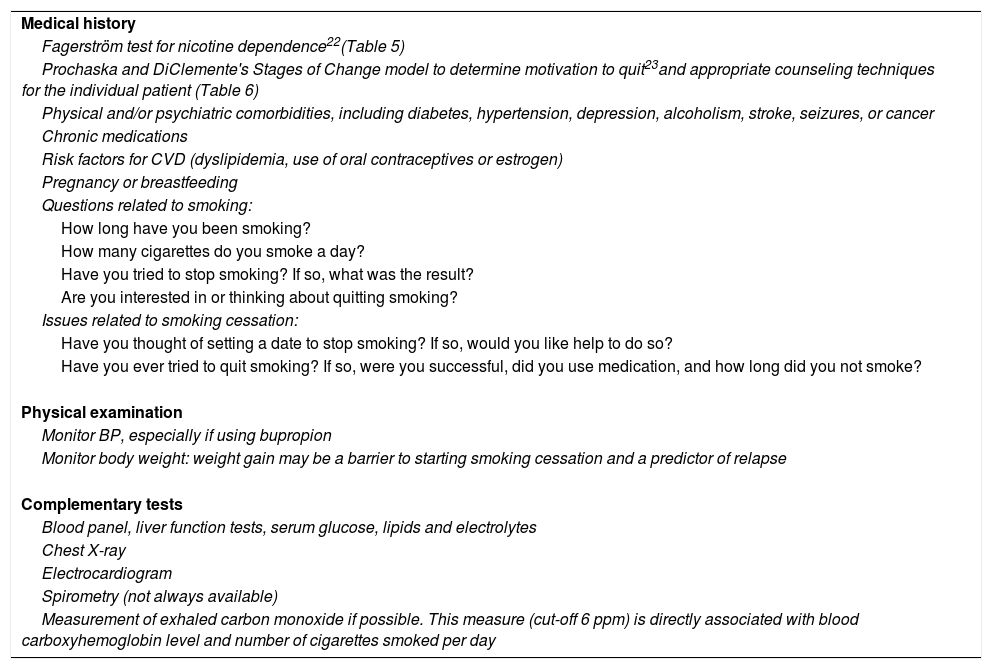

The approach to smokersMost smokers are aware that tobacco is harmful to their health. However, in most cases this is not sufficient incentive for them to give up smoking. Similarly, physicians recognize the harmful effects of smoking, but in daily practice tend to prioritize disease treatment instead of prevention. The initial approach should be to encourage smokers to start treatment regardless of their clinical condition and the level of their habit (Tables 4-6). The benefits of quitting smoking should be emphasized to all patients at every consultation with a healthcare professional. As many countries have restrictions on smoking in public places, it is important to raise the topic of exposure to tobacco smoke with all smokers if they live or spend time with non-smokers, especially young people who may consider smoking as normal and not harmful to their health. Furthermore, individuals with asthma may present acute worsening when exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke. Table 7 lists common measures to monitor smoking cessation.

Initial assessment in the approach to smokers.

| Medical history |

| Fagerström test for nicotine dependence22(Table 5) |

| Prochaska and DiClemente's Stages of Change model to determine motivation to quit23and appropriate counseling techniques for the individual patient (Table 6) |

| Physical and/or psychiatric comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, depression, alcoholism, stroke, seizures, or cancer |

| Chronic medications |

| Risk factors for CVD (dyslipidemia, use of oral contraceptives or estrogen) |

| Pregnancy or breastfeeding |

| Questions related to smoking: |

| How long have you been smoking? |

| How many cigarettes do you smoke a day? |

| Have you tried to stop smoking? If so, what was the result? |

| Are you interested in or thinking about quitting smoking? |

| Issues related to smoking cessation: |

| Have you thought of setting a date to stop smoking? If so, would you like help to do so? |

| Have you ever tried to quit smoking? If so, were you successful, did you use medication, and how long did you not smoke? |

| Physical examination |

| Monitor BP, especially if using bupropion |

| Monitor body weight: weight gain may be a barrier to starting smoking cessation and a predictor of relapse |

| Complementary tests |

| Blood panel, liver function tests, serum glucose, lipids and electrolytes |

| Chest X-ray |

| Electrocardiogram |

| Spirometry (not always available) |

| Measurement of exhaled carbon monoxide if possible. This measure (cut-off 6 ppm) is directly associated with blood carboxyhemoglobin level and number of cigarettes smoked per day |

CVD: cardiovascular disease.

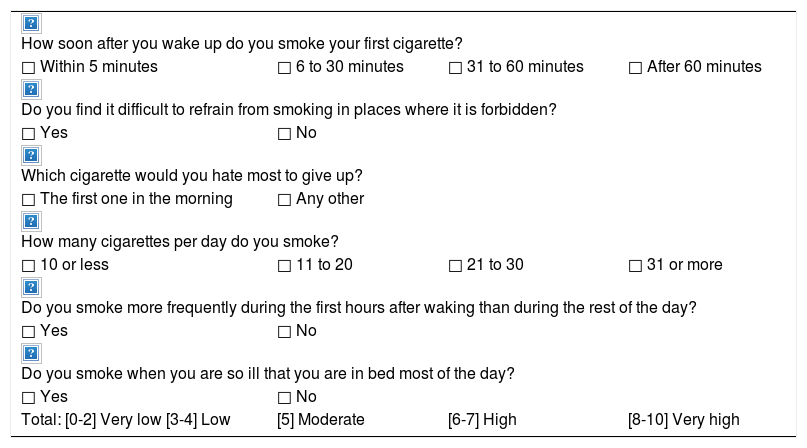

Fagerström test for nicotine dependence.22

| How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette? | |||

| □ Within 5 minutes | □ 6 to 30 minutes | □ 31 to 60 minutes | □ After 60 minutes |

| Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden? | |||

| □ Yes | □ No | ||

| Which cigarette would you hate most to give up? | |||

| □ The first one in the morning | □ Any other | ||

| How many cigarettes per day do you smoke? | |||

| □ 10 or less | □ 11 to 20 | □ 21 to 30 | □ 31 or more |

| Do you smoke more frequently during the first hours after waking than during the rest of the day? | |||

| □ Yes | □ No | ||

| Do you smoke when you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day? | |||

| □ Yes | □ No | ||

| Total: [0-2] Very low [3-4] Low | [5] Moderate | [6-7] High | [8-10] Very high |

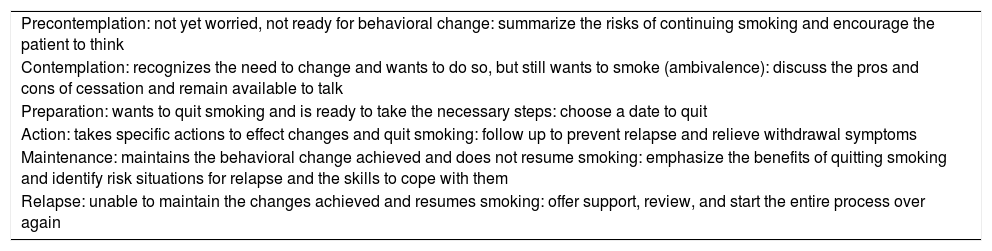

Stages of change and corresponding counseling techniques.23

| Precontemplation: not yet worried, not ready for behavioral change: summarize the risks of continuing smoking and encourage the patient to think |

| Contemplation: recognizes the need to change and wants to do so, but still wants to smoke (ambivalence): discuss the pros and cons of cessation and remain available to talk |

| Preparation: wants to quit smoking and is ready to take the necessary steps: choose a date to quit |

| Action: takes specific actions to effect changes and quit smoking: follow up to prevent relapse and relieve withdrawal symptoms |

| Maintenance: maintains the behavioral change achieved and does not resume smoking: emphasize the benefits of quitting smoking and identify risk situations for relapse and the skills to cope with them |

| Relapse: unable to maintain the changes achieved and resumes smoking: offer support, review, and start the entire process over again |

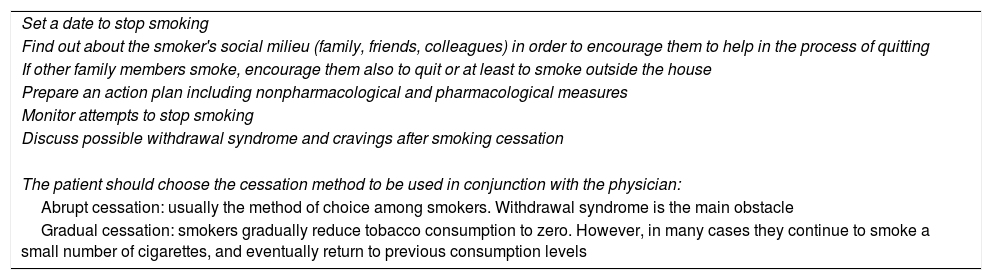

Follow-up of smoking cessation.

| Set a date to stop smoking |

| Find out about the smoker's social milieu (family, friends, colleagues) in order to encourage them to help in the process of quitting |

| If other family members smoke, encourage them also to quit or at least to smoke outside the house |

| Prepare an action plan including nonpharmacological and pharmacological measures |

| Monitor attempts to stop smoking |

| Discuss possible withdrawal syndrome and cravings after smoking cessation |

| The patient should choose the cessation method to be used in conjunction with the physician: |

| Abrupt cessation: usually the method of choice among smokers. Withdrawal syndrome is the main obstacle |

| Gradual cessation: smokers gradually reduce tobacco consumption to zero. However, in many cases they continue to smoke a small number of cigarettes, and eventually return to previous consumption levels |

Most smokers require cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Table 8) backed by pharmacological support to cope with withdrawal syndrome, which typically lasts between two and four weeks.

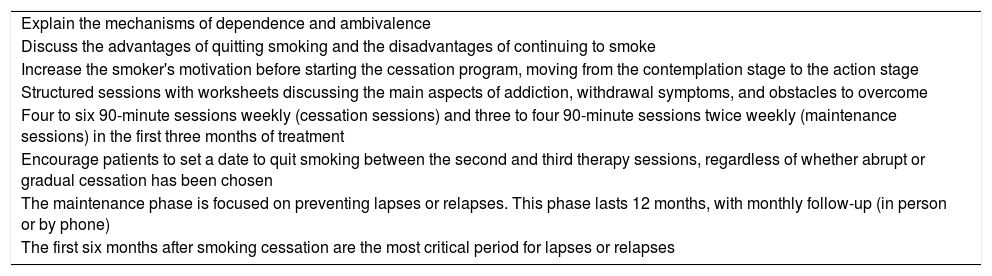

Cognitive behavioral therapy.

| Explain the mechanisms of dependence and ambivalence |

| Discuss the advantages of quitting smoking and the disadvantages of continuing to smoke |

| Increase the smoker's motivation before starting the cessation program, moving from the contemplation stage to the action stage |

| Structured sessions with worksheets discussing the main aspects of addiction, withdrawal symptoms, and obstacles to overcome |

| Four to six 90-minute sessions weekly (cessation sessions) and three to four 90-minute sessions twice weekly (maintenance sessions) in the first three months of treatment |

| Encourage patients to set a date to quit smoking between the second and third therapy sessions, regardless of whether abrupt or gradual cessation has been chosen |

| The maintenance phase is focused on preventing lapses or relapses. This phase lasts 12 months, with monthly follow-up (in person or by phone) |

| The first six months after smoking cessation are the most critical period for lapses or relapses |

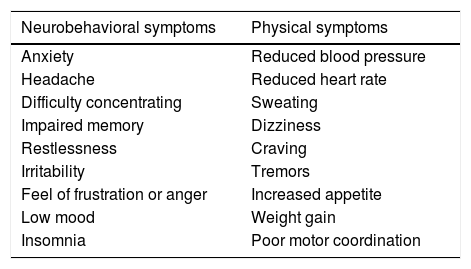

The main signs and symptoms of withdrawal syndrome are listed in Table 9.

Symptoms of nicotine withdrawal syndrome.

| Neurobehavioral symptoms | Physical symptoms |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | Reduced blood pressure |

| Headache | Reduced heart rate |

| Difficulty concentrating | Sweating |

| Impaired memory | Dizziness |

| Restlessness | Craving |

| Irritability | Tremors |

| Feel of frustration or anger | Increased appetite |

| Low mood | Weight gain |

| Insomnia | Poor motor coordination |

Inhaled nicotine binds to specific neuronal receptors that cause the brain to release dopamine and endorphins, whose effects are perceived by the smoker as stimulating and pleasurable via the reward circuit of the limbic system. Dopamine reuptake dissipates these effects and the receptors signal the need for a new stimulus (that is, they demand more nicotine), which is perceived as an unpleasant sensation. Regular smokers experience withdrawal every day, whenever they are unable to smoke for even a short time.15

Craving, defined as an urgent desire to smoke, is a classic symptom of physical nicotine dependence. Nicotine deprivation produces various physical effects that may last from seven to 30 days; they are stronger in the first three days after quitting smoking. However, craving may persist for many months if the environmental stimuli that have long been associated with smoking persist, and these associations are difficult to break. In order to deal with these situations, the former smoker needs to develop skills and strategies to avoid triggering factors leading to lapse and relapse.

Pharmacotherapy should be used to supplement CBT and alleviate withdrawal symptoms. Medications should be used for three months, extending to six months for individuals who find it more difficult to quit smoking.13 With pharmacological therapy, it has been estimated that one person successfully quits (defined as six-month abstinence) for every 6-23 people treated.11

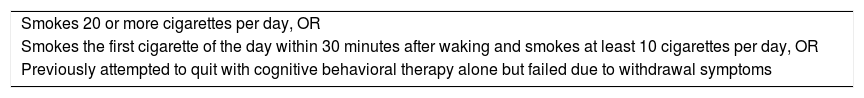

Table 10 summarizes the criteria for the initiation of pharmacological therapy, which should always take into account the patient's comfort, safety, and preference, as well as possible contraindications for the use of a particular drug.

Criteria for initiation of pharmacological therapy.

| Smokes 20 or more cigarettes per day, OR |

| Smokes the first cigarette of the day within 30 minutes after waking and smokes at least 10 cigarettes per day, OR |

| Previously attempted to quit with cognitive behavioral therapy alone but failed due to withdrawal symptoms |

The medications used are divided into two basic categories: nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and non-NRT.

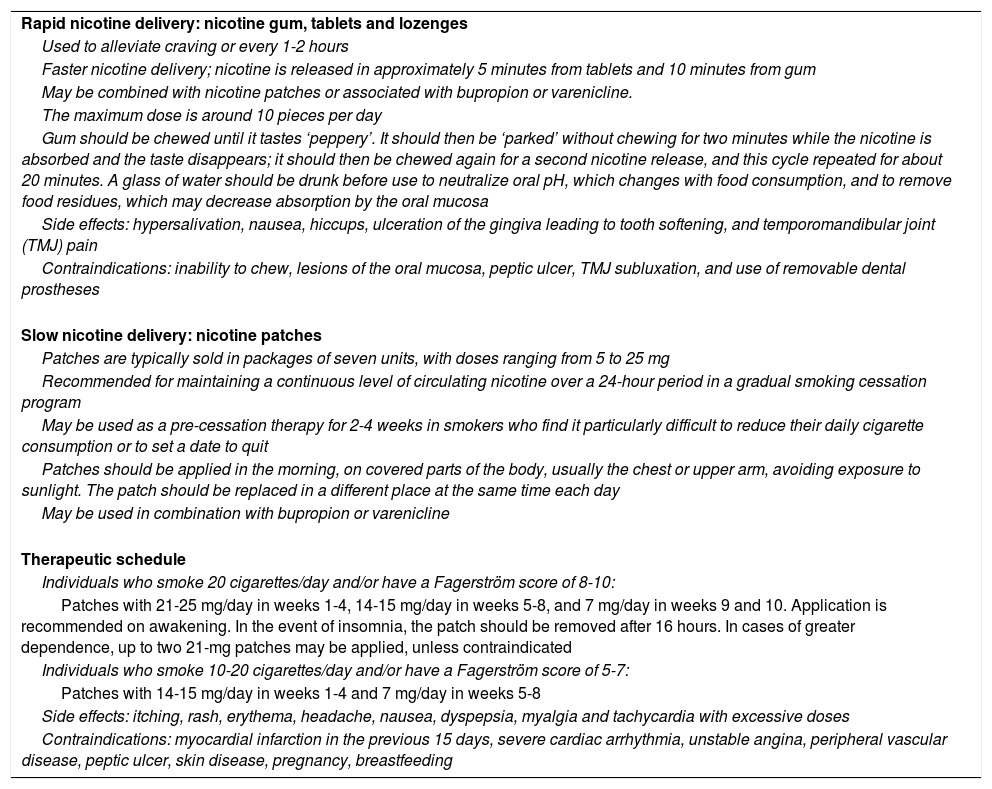

NRT is the first-line treatment approach for smokers and is indicated for those with moderate to high dependence levels according to the Fagerström test. NRT should not be combined with smoking. Patients should be told to stop smoking up to 14 days after beginning NRT. The number needed to treat (NNT) for long-term cessation is 23, while for premature death it is 46.11 NRT is available in the form of slow release (usually 24-hour) patches, chewing gum (usually 2 or 4 mg), and nicotine tablets and lozenges (usually 2 or 4 mg). Table 11 describes the use of NRT for smoking cessation.11–15

Nicotine replacement therapy.

| Rapid nicotine delivery: nicotine gum, tablets and lozenges |

| Used to alleviate craving or every 1-2 hours |

| Faster nicotine delivery; nicotine is released in approximately 5 minutes from tablets and 10 minutes from gum |

| May be combined with nicotine patches or associated with bupropion or varenicline. |

| The maximum dose is around 10 pieces per day |

| Gum should be chewed until it tastes ‘peppery’. It should then be ‘parked’ without chewing for two minutes while the nicotine is absorbed and the taste disappears; it should then be chewed again for a second nicotine release, and this cycle repeated for about 20 minutes. A glass of water should be drunk before use to neutralize oral pH, which changes with food consumption, and to remove food residues, which may decrease absorption by the oral mucosa |

| Side effects: hypersalivation, nausea, hiccups, ulceration of the gingiva leading to tooth softening, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain |

| Contraindications: inability to chew, lesions of the oral mucosa, peptic ulcer, TMJ subluxation, and use of removable dental prostheses |

| Slow nicotine delivery: nicotine patches |

| Patches are typically sold in packages of seven units, with doses ranging from 5 to 25 mg |

| Recommended for maintaining a continuous level of circulating nicotine over a 24-hour period in a gradual smoking cessation program |

| May be used as a pre-cessation therapy for 2-4 weeks in smokers who find it particularly difficult to reduce their daily cigarette consumption or to set a date to quit |

| Patches should be applied in the morning, on covered parts of the body, usually the chest or upper arm, avoiding exposure to sunlight. The patch should be replaced in a different place at the same time each day |

| May be used in combination with bupropion or varenicline |

| Therapeutic schedule |

| Individuals who smoke 20 cigarettes/day and/or have a Fagerström score of 8-10: |

| Patches with 21-25 mg/day in weeks 1-4, 14-15 mg/day in weeks 5-8, and 7 mg/day in weeks 9 and 10. Application is recommended on awakening. In the event of insomnia, the patch should be removed after 16 hours. In cases of greater dependence, up to two 21-mg patches may be applied, unless contraindicated |

| Individuals who smoke 10-20 cigarettes/day and/or have a Fagerström score of 5-7: |

| Patches with 14-15 mg/day in weeks 1-4 and 7 mg/day in weeks 5-8 |

| Side effects: itching, rash, erythema, headache, nausea, dyspepsia, myalgia and tachycardia with excessive doses |

| Contraindications: myocardial infarction in the previous 15 days, severe cardiac arrhythmia, unstable angina, peripheral vascular disease, peptic ulcer, skin disease, pregnancy, breastfeeding |

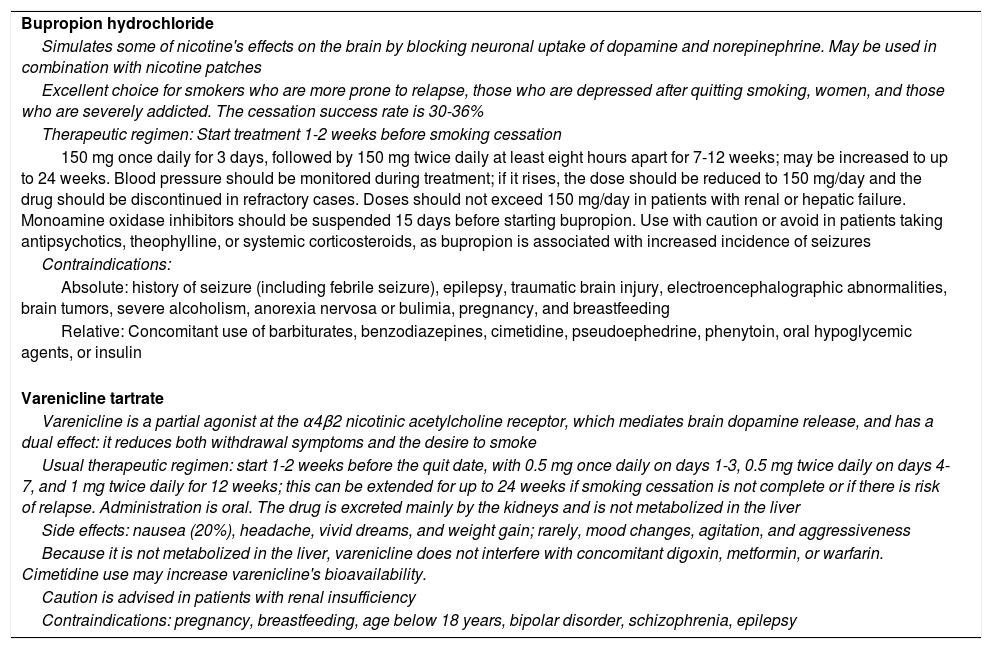

Bupropion and varenicline are the first-line non-NRT medications (Table 12).11–15 Clonidine and nortriptyline are second-line options, due to their side effects. The NNT for bupropion and varenicline is 18 and 10, respectively, for long-term cessation, and 36 and 20, respectively, for premature death.11Table 13 summarizes common pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation.11–15

Non-nicotine replacement therapy.

| Bupropion hydrochloride |

| Simulates some of nicotine's effects on the brain by blocking neuronal uptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. May be used in combination with nicotine patches |

| Excellent choice for smokers who are more prone to relapse, those who are depressed after quitting smoking, women, and those who are severely addicted. The cessation success rate is 30-36% |

| Therapeutic regimen: Start treatment 1-2 weeks before smoking cessation |

| 150 mg once daily for 3 days, followed by 150 mg twice daily at least eight hours apart for 7-12 weeks; may be increased to up to 24 weeks. Blood pressure should be monitored during treatment; if it rises, the dose should be reduced to 150 mg/day and the drug should be discontinued in refractory cases. Doses should not exceed 150 mg/day in patients with renal or hepatic failure. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should be suspended 15 days before starting bupropion. Use with caution or avoid in patients taking antipsychotics, theophylline, or systemic corticosteroids, as bupropion is associated with increased incidence of seizures |

| Contraindications: |

| Absolute: history of seizure (including febrile seizure), epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, electroencephalographic abnormalities, brain tumors, severe alcoholism, anorexia nervosa or bulimia, pregnancy, and breastfeeding |

| Relative: Concomitant use of barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cimetidine, pseudoephedrine, phenytoin, oral hypoglycemic agents, or insulin |

| Varenicline tartrate |

| Varenicline is a partial agonist at the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, which mediates brain dopamine release, and has a dual effect: it reduces both withdrawal symptoms and the desire to smoke |

| Usual therapeutic regimen: start 1-2 weeks before the quit date, with 0.5 mg once daily on days 1-3, 0.5 mg twice daily on days 4-7, and 1 mg twice daily for 12 weeks; this can be extended for up to 24 weeks if smoking cessation is not complete or if there is risk of relapse. Administration is oral. The drug is excreted mainly by the kidneys and is not metabolized in the liver |

| Side effects: nausea (20%), headache, vivid dreams, and weight gain; rarely, mood changes, agitation, and aggressiveness |

| Because it is not metabolized in the liver, varenicline does not interfere with concomitant digoxin, metformin, or warfarin. Cimetidine use may increase varenicline's bioavailability. |

| Caution is advised in patients with renal insufficiency |

| Contraindications: pregnancy, breastfeeding, age below 18 years, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, epilepsy |

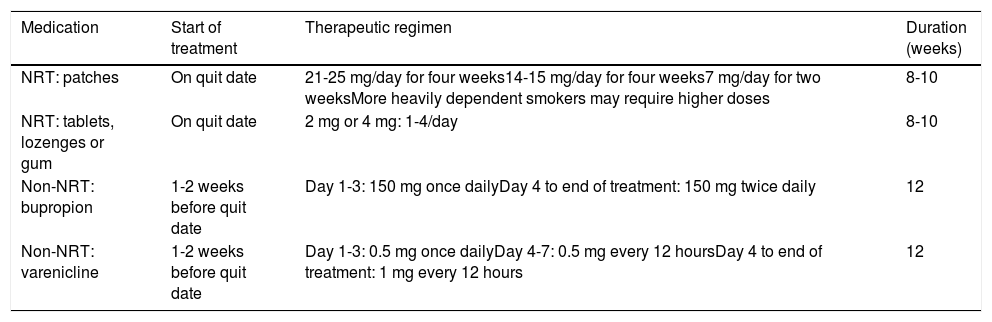

Common pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation.

| Medication | Start of treatment | Therapeutic regimen | Duration (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRT: patches | On quit date | 21-25 mg/day for four weeks14-15 mg/day for four weeks7 mg/day for two weeksMore heavily dependent smokers may require higher doses | 8-10 |

| NRT: tablets, lozenges or gum | On quit date | 2 mg or 4 mg: 1-4/day | 8-10 |

| Non-NRT: bupropion | 1-2 weeks before quit date | Day 1-3: 150 mg once dailyDay 4 to end of treatment: 150 mg twice daily | 12 |

| Non-NRT: varenicline | 1-2 weeks before quit date | Day 1-3: 0.5 mg once dailyDay 4-7: 0.5 mg every 12 hoursDay 4 to end of treatment: 1 mg every 12 hours | 12 |

NRT: nicotine replacement therapy.

Since smoking has effects at the population level and poses risks not only for smokers but also for non-smokers, pregnant women, fetuses, and children, as well as consuming large quantities of public resources, both financial and organizational, and causes dependence in smokers in a similar fashion to those addicted to other drugs, medical care and health education are not in themselves sufficient. Legislation must aim to control the exploitation and use of tobacco in all its forms, just like any other addictive drug.

The economic interests involved in tobacco cultivation, production, processing, marketing, and advertising are large and cross national borders. This means that classifying and dealing with tobacco solely as a medical and healthcare issue is inadequate. In response, in 2003 the WHO launched the FCTC,9 since ratified by 168 countries, which have committed to observing certain principles that are to be progressively incorporated into their laws. The health sectors in all signatory countries are required to monitor the implementation of these principles and to ensure that both the general population and policy-makers remain aware of them.

The FCTC was signed and ratified by the PSCs on the following dates: Angola (June 29, 2004/September 20, 2007), Brazil (June 16, 2003/November 03, 2005), Cape Verde (February 17, 2004/October 4, 2005), Equatorial Guinea (April 1st, 2004/November 7, 2007), Guinea-Bissau (accession November 7, 2008), Mozambique (June 18, 2004/July 14, 2017), Portugal (January 9, 2004/November 8, 2005), São Tomé and Príncipe (June 18, 2004/April 12, 2006), and East Timor (May 25, 2004/December 22, 2004).24,25

Organizations focused specifically on monitoring compliance with the treaty and related political actions have emerged in many countries, such as the Alliance for Tobacco Control and Health Promotion in Brazil (http://actbr.org.br/). Non-governmental organizations, national associations and committees within medical societies and in other healthcare segments are involved in mobilizing society, coordinating actions, and keeping tobacco control measures up-to-date.24,25

ConclusionsTobacco use in all forms represents a serious public health problem in terms of the prevention and treatment of chronic non-communicable diseases. General practitioners, internists, cardiologists and other specialists should identify patients who smoke, make themselves familiar with and apply all available tools to encourage smokers to seek professional help to quit smoking, and take advantage of key opportunities like a diagnosis of coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial or cerebrovascular disease, or tobacco-related cancer, to raise awareness of the dangers of tobacco among patients, their family, and opinion-formers. Increasing awareness in the general population of the risks of tobacco use makes this a favorable time to approach smokers. Treatment is now more accessible (NRT and bupropion are available in the PSCs) and can be performed at any healthcare level.

The association of CBT with pharmacological support to cope with withdrawal increases the effectiveness of interventions. Relapses are part of the smoking dependence cycle and should be viewed as a lesson that will make a subsequent attempt more likely to succeed. Cessation of smoking at any age brings health benefits to the smoker and to those around them, and physicians should always be ready to offer care, irrespective of the individual's stage in the cessation process.

New forms of tobacco use, especially using electronic systems, are far from proven to be harmless, even if they may contribute to reducing overall tobacco consumption and its harmful effects, and their use should be discouraged.

Smoking must be considered as a problem that goes beyond the damage caused to the organs affected by tobacco smoke and associated products, but is part of a series of problems produced by human society, with economic, social, cultural, and ecological aspects that affect quality of life and survival itself.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de Oliveira GM, Mendes M, Dutra ÓP, et al. Recomendações de 2019 para a redução do consumo de tabaco nos países de língua portuguesa. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:233–244.