The World Health Organization goal's to reduce mortality due to chronic non-communicable diseases by 2% per year demands a huge effort from member countries. This challenge for health professionals requires global political action on implementation of social measures, with cost-effective population interventions to reduce chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors. Systemic arterial hypertension is highly prevalent in Portuguese-speaking countries, and is a major risk factor for complications such as stroke, acute myocardial infarction and chronic kidney disease, rivaling dyslipidemia and obesity in importance for the development of atherosclerotic disease. Joint actions to implement primary prevention measures can reduce outcomes related to hypertensive disease, especially ischemic heart disease and stroke. It is essential to ensure the implementation of guidelines for the management of systemic hypertension via a continuous process involving educational actions, lifestyle changes and guaranteed access to pharmacological treatment.

A meta da Organização Mundial da Saúde de reduzir a mortalidade por doenças crônicas não transmissíveis em 2% ao ano exige um enorme esforço por parte dos países. Esse grande desafio lançado pela Organização Mundial de Saúde requer uma ação política global e concertada através de medidas nas comunidades, com intervenções populacionais de cunho custo-efetivo para reduzir prevalência das doenças crónicas não transmissíveis e dos seus fatores de risco. A hipertensão arterial tem grande prevalência nas populações dos países de língua portuguesa e representa o principal fator de risco para complicações como acidente vascular cerebral, enfarte agudo do miocárdio e doença renal crónica, correspondendo em importância à dislipidemia e obesidade para as doenças ateroscleróticas. Ações conjuntas que visem à implementação de medidas de prevenção primária poderão reduzir os desfechos relacionados com a doença hipertensiva, especialmente acidente vascular cerebral e enfarte agudo do miocárdio. Torna-se necessário garantir a implementação dessas diretrizes para o tratamento da HTA no terreno, através de um processo continuado, que envolva fundamentalmente ações de educação, de mudança do estilo de vida e garantia de acesso aos medicamentos.

The World Health Organization's goal to reduce mortality due to chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) by 2% per year demands a huge effort from member countries.1–4 This challenge for health professionals requires global political action on implementation of social measures, with cost-effective population interventions to reduce NCDs and their risk factors. Health professionals need their governments to implement acceptable cost measures, such as counseling for smoking cessation, guidance on healthy diets, encouragement of regular physical exercise, control of systemic arterial hypertension, and teaching and training programs aimed at these issues. These measures would contribute around 70% to the goal of a 2% per year reduction in NCDs.2,5 Dyslipidemia, hypertension and obesity are highly prevalent multifactorial diseases in Portuguese-speaking countries.5,6 Systemic hypertension is a major risk factor for complications such as stroke, myocardial infarction and chronic kidney disease, rivaling dyslipidemia and obesity in importance for the development of atherosclerotic disease.5,6 In addition to their significant epidemiological impact, non-pharmacological treatments of cardiovascular risk factors have a significant effect on the expenditure of ministries of health, social security and finance, because these conditions are major causes, directly or indirectly, of workplace absenteeism. There is evidence that preventive actions are more promising in the primary health care setting.

The number of adults with hypertension increased from 594 million in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015, of whom 597 million were men and 529 million women. This increase is due to both population growth and aging.6 Analysis of trends in blood pressure (BP) levels of 19.1 million adults from several population studies in the past four decades (1975-2015) shows that the highest BP levels have shifted from high-income to low- and middle-income countries of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. However, BP levels remain high in Eastern and Central Europe and Latin America.6

Several trends have been identified in changes in proportional mortality due to hypertensive disease and its outcomes, ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, in Portuguese-speaking countries from 1990 to 2015 (Table 1). The highest proportional mortality rates due to hypertensive disease were observed in Brazil, Mozambique and Angola. Portugal had the highest human development index in 2015 and the highest mortality due to stroke.7–9 Limited access (around 50-65%) to essential pharmacological treatment in low- and low-middle income countries may have contributed to these results. In addition, in 40% of these countries there is less than one physician per 1000 population, and few hospital beds for the care of outcomes related to uncontrolled hypertension.7 Thus, joint actions to implement primary prevention measures can reduce outcomes related to hypertensive disease, especially IHD and stroke. It is essential to ensure the implementation of guidelines for the management of hypertension via a continuous process involving educational actions, lifestyle changes and guaranteed access to pharmacological treatment.

Annual percentage changes in proportional mortality in both sexes and all ages between 1990 and 2015 due to hypertensive disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke, and human development index and population in 2015, in Portuguese-speaking countries.

| Country | Hypertensive disease | IHD | Stroke | HDI (2015) | Population (2015a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportional mortality (annual % change) | |||||

| Brazil | 1.77 (+1.79) | 14.44 (+0.44) | 10.61 (+0.12) | 0.754a | 205002000 |

| Mozambique | 1.46 (+0.27) | 3.84 (+1.25) | 5.37 (+0.52) | 0.418a | 25727911 |

| Angola | 1.28 (-0.97) | 4.65 (-0.96) | 5.35 (-1.09) | 0.533a | 25789024 |

| Portugal | 1.08 (+1.20) | 12.71 (-1.32) | 14.96 (-2.32) | 0.843a | 10374822 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 0.53 (-0.43) | 4.87 (+0.25) | 5.07 (+0.22) | 0.424a | 1844000 |

| East Timor | 1.33 (+0.38) | 11.84 (+1.16) | 10.02 (+0.57) | 0.605a | 1212107 |

| Macao | NA | NA | NA | 0.566b | 642900 |

| Cape Verde | 0.75 (-0.62) | 11.74 (+1.34) | 13.74 (-0.18) | 0.648a | 524833 |

| São Tomé and Principe | 0.44 (-0.55) | 8.18 (-0.41) | 10.22 (-0.18) | 0.574a | 190000 |

HDI: human development index; IHD: ischemic heart disease; NA: not available.

Last year available: 2014.

Sources: World Health Statistics 2017: Monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 20177; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables8; Global Health Data Exchange.9

The risk associated with high BP increases with age, and every 2-mmHg rise is associated with a 7% and 10% increase in the risk of death due to IHD and stroke, respectively.2

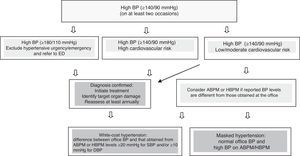

Hypertension is defined as systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mmHg at least on two occasions. BP can be assessed in the physician's office by either automated or auscultatory methods. The classification of BP according to office BP values for individuals aged over 18 years is shown in Table 2. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring (HBPM) can help in the diagnosis of white-coat hypertension (WCH) and masked hypertension (MH). In WCH, BP measured at the office is high and that measured with ABPM or HBPM is normal, while in MH, the opposite is the case (Figure 1). In both WCH and MH, ABPM is mandatory. Figure 1 shows a flowchart for the diagnosis of hypertension.

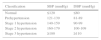

Blood pressure classification according to office blood pressure values for individuals aged over 18 years.

| Classification | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | ≤120 | ≤80 |

| Prehypertension | 121-139 | 81-89 |

| Stage 1 hypertension | 140-159 | 90-99 |

| Stage 2 hypertension | 160-179 | 100-109 |

| Stage 3 hypertension | ≥180 | ≥110 |

When SBP and DBP are in different categories, the higher should be used to classify BP. Systolic hypertension is considered isolated if SBP ≥140 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg, and is classified as stage 1, 2 or 3.

Reproduced with permission from Malachias et al.1

ABPM enables identification of circadian BP changes, especially those related to sleep. In ABPM, BP is considered elevated when 24-hour BP is ≥130/80 mmHg, ranging from ≥135/85 mmHg when awake to ≥120/70 mmHg when sleeping. For HBPM, BP is considered elevated when ≥135/85 mmHg.1

Recommended blood pressure measurement techniquePatients should be previously informed about the procedure, and the steps in Table 3 should be followed.3,10,11 Blood pressure should be measured by all health professionals on every clinical assessment and at least once a year.

Recommended technique for measuring office blood pressure using the auscultatory method.

| BP should be measured with a validated, calibrated and accurate sphygmomanometer, with an appropriate cuff size for arm circumference, according to the manufacturer's recommendation: cuff width should be close to 40% and cuff length should cover 80-100% of arm circumference. |

| The cuff should be placed snugly, 2-3 cm above the cubital fossa, with its bladder centered on the brachial artery, and the arm supported at the level of the heart. |

| The patient should rest in a calm environment for 5 min, sitting in a chair with back supported, legs uncrossed and feet on the floor. The patient should be relaxed and should not have exercised in the previous 30 min, or consumed tobacco, alcohol or high-energy foods or drinks (including coffee) in the previous hour. |

| BP can also be measured after two min in the supine position with the arm supported, especially for diabetics and the elderly, and after 2 min of standing when orthostatic hypotension is suspected. BP measurement in the sitting position is used for therapeutic decision-making, while measurement in the standing position aids treatment changes in cases of orthostatic hypotension. |

| The pressure should be increased rapidly to 30 mmHg above the level at which the radial pulse can no longer be palpated, and then the cuff should be deflated at approximately 2 mmHg/beat. SBP is determined by auscultation of the first sound (Korotkoff phase I), and DBP by disappearance of the sounds (Korotkoff phase V). If the sounds persist until level zero, muffling of sounds (Korotkoff phase IV) is used to determine DBP. |

| The first reading should be discarded, and two sequential readings in both arms should be taken, the higher one being recorded. If arrhythmia is present, more measurements should be taken to determine mean BP. |

| The patient's BP reading should be recorded. |

| BP levels should be reassessed at least monthly until control is achieved, and then every three months. |

BP: blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Complementary assessment is aimed at detecting target organ damage (TOD), aiding cardiovascular risk stratification and identifying signs of secondary hypertension.

TOD should be investigated with the recommended complementary tests (routine and for specific populations) shown in Table 4, in addition to screening for the following conditions:

- •

Left ventricular hypertrophy, assessed on electrocardiogram: Sokolow-Lyon index (S in V1+R in V5 or V6 [whichever is larger]) >35 mm and Ra in VL >1.1 mV; Cornell index (S in V3+R in aVL >28 mm in men and >20 mm in women); or on echocardiogram: left ventricular mass index ≥116 g/m2 (men) and ≥96 g/m2 (women);

- •

Atherosclerotic disease in other sites and chronic kidney disease stage ≥3 (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2) (Table 5).

Table 5.Stratification based on risk factors, target organ damage and cardiovascular or kidney disease.

CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HTN: hypertension; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TOD: target organ damage.

Adapted with permission from Malachias et al.1

Recommended complementary tests (routine and for specific populations).

| Routine tests for all hypertensive patients | |

|---|---|

| Urine analysis | Fasting glycemia and HbA1c |

| eGFR | Total cholesterol, HDL-C and serum triglycerides |

| Conventional ECG | Serum creatinine, potassium and uric acid levels |

| Recommended tests to screen for TOD in specific populations | |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray | Clinical suspicion of cardiac and/or pulmonary dysfunction Aortic dilatation or aneurysm (if echocardiogram is not available) Suspicion of aortic coarctation |

| Echocardiogram | Evidence of LVH on ECG or clinically suspected HF LVH (when LV mass corrected for BSA ≥116 g/m2 for men or 96 g/m2 for women) |

| Albuminuria | Diabetic hypertensive patients, with metabolic syndrome or at least two risk factors (normal values <30 mg/24 h) |

| Carotid ultrasound | Carotid murmur, signs of CVD, atherosclerotic disease in other sites IMT >0.9 mm and/or atherosclerotic plaques |

| Renal ultrasound or Doppler | Patients with abdominal masses or abdominal murmurs |

| Exercise test | Suspicion or family history of CAD or diabetes |

| Brain MRI | Patients with cognitive disorders or dementia Detection of silent infarctions and microhemorrhages |

BSA: body surface area; CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; ECG: electrocardiogram; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HF: heart failure; IMT: intima-media thickness; LV: left ventricular; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; TOD: target organ damage.

Risk stratification should consider classical risk factors, relating them to BP levels as shown in Table 5.

The following are considered risk factors:

- •

male gender and age (men >55 years and women >65 years);

- •

smoking,

- •

dyslipidemia (triglycerides >150 mg/dl, low density lipoprotein cholesterol >100 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dl),

- •

obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2),

- •

abdominal obesity (waist circumference >102 cm for men and >88 cm for women),

- •

diabetes, abnormal oral glucose tolerance test or fasting blood glucose 102-125 mg/dl,

- •

family history of premature cardiovascular disease (men <55 years and women <65 years).

Blood pressure reduction is associated with a significant reduction in cardiovascular risk that is higher in individuals at high cardiovascular risk, with a smaller risk reduction in other individuals.2,11 Non-pharmacological therapy with lifestyle changes should be initially implemented for all stages of hypertension and for individuals with BP 135-139/85-89 mmHg (Table 6). For stage 1 hypertensives at low or intermediate cardiovascular risk, management can start with lifestyle changes for 3-6 months before deciding whether to start pharmacological treatment. For other stages, antihypertensive therapy should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is established.

Recommendations for non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension.

| Measure | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight control | Maintain BMI <25 kg/m2 up to 65 years of age Maintain BMI <27 kg/m2 after 65 years of age Maintain WC <88 cm for women and <102 cm for men | |

| Diet | Adopt a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, low in saturated fat. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, with an energy intake of 2100 kcal/day as originally proposed, is the most used: | |

| Fruit (portions/day) | 4-5 | |

| Vegetables (portions/day) | 4-5 | |

| Milk and dairy products <1% fat (portions/day) | 2-3 | |

| Lean meat, fish and poultry (g/day) | <180 | |

| Oils and fats (portions/day) | 2-3 | |

| Seeds and nuts (portions/week) | 4-5 | |

| Added sugars (portions/week) | 5 | |

| Salt (portion/day) | ∼6 g (3000 mg sodium) | |

| Whole grains (portions/day) | 6-8 | |

| Alcohol | Limit daily alcohol consumption to one dose for women and low-weight individuals, and two doses for men. | |

| Exercise | Exercise is recommended for all hypertensives: Moderate, continuous (one 30-min session) or cumulative (two 15-min or three 10-min sessions) exercise (walking or similar) for at least 30 min/day, 5-7 days/week | |

| Aerobic training At least 3 times/week (ideally 5 times/week), minimum of 30 min (ideally 40-50 min) Several exercise types, such as walking, running, dancing, swimming Moderate intensity is defined as exertion that still allows talking (without breathlessness) and a sensation of mild to moderate fatigue Maintain THR between lower and upper limits calculated as follows: Lower limit=(maximum HR-resting HR)×0.5+resting HRa; upper limit=(maximum HR-resting HR)×0.7+resting HRa Ideally, the HR used to calculate the intensity of aerobic training should be determined on a maximal exercise test, with patients on their usual medication | ||

| Resistance training 2-3 times/week, 8-10 exercises for the large muscle groups, prioritizing unilateral exercise when possible 1-3 sets with 10-15 repetitions up to moderate fatigue (reducing speed of movement and avoiding apnea, exhaling during contraction and inhaling when returning to the initial position) Long passive pauses: 90-120 s | ||

Maximum HR: obtained either on a maximal exercise test with regular medications, or by estimating maximum HR according to age (220-age; not to be used for individuals with heart disease or hypertensives on beta-blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers). Resting HR: measured after a 5-min rest in a supine position.

BMI: body mass index; HR: heart rate; THR: training heart rate; WC: waist circumference.

Adapted with permission from Malachias et al.1

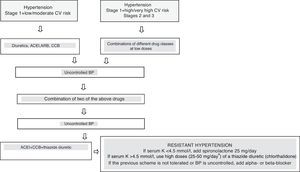

A target BP of less than 130/80 mmHg is recommended for individuals at high cardiovascular risk, including those with diabetes, and less than 140/90 mmHg for stage 3 hypertensives. For patients with coronary artery disease, BP should not be lower than 120/70 mmHg because of the risk of coronary hypoperfusion, myocardial damage and cardiovascular events. For hypertensives aged ≥80 years, BP should be less than 145/85 mmHg. Figure 2 shows the pharmacological approach to hypertension.

Flowchart for the treatment of arterial hypertension.12–14 ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; BP: blood pressure; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CV: cardiovascular; K: potassium. a High doses of chlorthalidone should be used instead of another thiazide unless it has been used previously.

Adapted with permission from Malachias et al.1

When angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) are not tolerated, they should be replaced with low-cost angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Beta-blockers should be considered for young individuals intolerant of ACEIs and ARBs, breastfeeding women, individuals with increased adrenergic tone, and those with IHD or heart failure (HF). In cases of intolerance to calcium channel blockers (CCBs) because of edema, or HF or suspected HF, thiazide diuretics can be used (chlorthalidone 12.5-25 mg once daily or indapamide 1.5-2.5 mg once daily). Individuals with dark skin should be prescribed ARBs rather than ACEIs in pharmacological combinations.2,11–14

Approximately two-thirds of patients will need combinations of at least two drugs to control BP. The advantage of such associations is the synergy of different mechanisms of action that enables lower doses and thus fewer adverse effects, in addition to better therapeutic adherence.

No specific drug class is indicated to treat a hypertensive patient with previous stroke, but target BP should be less than 130/80 mmHg.

Table 7 depicts the clinical situations with indication for or contraindication to specific drugs. For chronic kidney disease, ACEIs and ARBs reduce albuminuria, and thiazide diuretics are used for stages 1 to 3, while loop diuretics are used for stages 4 and 5.2,11–14

Indications and contraindications for antihypertensive drugs in different clinical situations.

| Drugs with specific indications | |

|---|---|

| Clinical situation | Indicated initial therapy |

| Heart failure | ACEIs/ARBs, diuretics, BBs |

| MI, angina, PCI or CABG | ACEIs/ARBs, BBs, aspirin, statins |

| Diabetes | Thiazide diuretics, ACEIs/CCBs,a BBs |

| Chronic renal failure | ACEIs/ARBs, loop diuretics |

| Metabolic syndrome | CCBs, ACEIs/ARBs |

| Aortic aneurysm | BBs |

| PAD | ACEIs, CCBs |

| Pregnancy | Methyldopa, CCBs |

| Contraindicated drugs | |

|---|---|

| Clinical situation | Contraindicated therapy |

| Asthma and chronic bronchitis | Non-cardioselective BBs |

| Pregnancy | ACEIs/ARBs |

| AV block | BBs, nondihydropyridine CCBs |

| Gout | Diuretics |

| Bilateral renal artery stenosis | ACEIs, ARBs |

ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; AV: atrioventricular; BBs: beta-blockers; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CCBs: calcium channel blockers; MI: myocardial infarction; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Pregnant women with uncomplicated chronic hypertension should have BP levels lower than 150/100 mmHg, but DBP should not be <80 mmHg.1,2,11–14 ACEIs and ARBs are contraindicated during pregnancy, and atenolol and prazosin should be avoided. Methyldopa, beta-blockers (except atenolol), hydralazine and CCBs (nifedipine, amlodipine and verapamil) can be safely used.2,11–14

In chronic gestational hypertension with TOD, BP levels should be maintained under 140/90 mmHg, and the pregnant woman should be referred to a specialist for appropriate care during delivery and to avoid teratogenicity. Delivery should not be induced if BP <160/110 mmHg (with or without antihypertensive drugs) up to the 37th week. Fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume should be monitored by ultrasound between the 28th and 30th weeks and between the 32nd and 34th weeks, and by umbilical artery Doppler. During delivery, BP levels should be monitored continuously.1,2,12–14 During the puerperium period, BP levels should be maintained under 140/90 mmHg, preferably with drugs that are safe to use during breastfeeding: hydrochlorothiazide, spironolactone, alpha-methyldopa, propranolol, hydralazine, minoxidil, verapamil, nifedipine, nimodipine, nitrendipine, benazepril, captopril and enalapril.1,2,12–15

Pre-eclampsia is defined as hypertension after the 20th gestational week associated with significant proteinuria and may also be characterized by headache, blurred vision, abdominal pain, low platelet count (<100000/mm3), elevated liver enzymes (twice baseline level), renal dysfunction (creatinine >1.1 mg/dl or twice baseline level), pulmonary edema, cerebral disorders or visual disturbances. Eclampsia is defined as tonic-clonic seizures occurring in a woman with pre-eclampsia. Magnesium sulfate is recommended to prevent and treat eclampsia, at a loading dose of 4-6 g intravenously (IV) for 10-20 min, followed by infusion of 1-3 g/h, usually for 24 h after the seizure. In the event of relapse, 2-4 g IV can be administered. Corticosteroids, IV antihypertensives (hydralazine, labetalol) and blood volume expansion are recommended. Patients should be admitted to the intensive care unit.1,2,11–15

Table 8 lists reasons for failure to control BP. It is important to rule out pseudoresistance due to WCH.

Reasons for failure to control blood pressure.

| Poor adherence to medications, appropriate diet, and adequate exercise, and excessive consumption of salt, tobacco and alcohol |

| Associated conditions: overweight and obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic pain, blood volume overload, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disease |

| Drug interactions: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, anabolic steroids, sympathomimetic drugs, decongestants, amphetamines, erythropoietin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, licorice, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| Suboptimal therapeutic regimen, low drug doses, inappropriate combinations of antihypertensive drugs, renal sodium retention (pseudotolerance) |

| Secondary hypertension: renovascular disease, primary hyperaldosteronism, pheochromocytoma |

Adapted from Leung et al.11

The prevalence of secondary hypertension in the hypertensive population is around 3-5%. The most common cause (responsible for 2-5% of hypertension cases) is renal parenchymal disease. Adrenal causes and pheochromocytoma are found in fewer than 1% of cases of hypertension. However, 80% of patients with Cushing's syndrome have hypertension. Physicians should maintain a high level of clinical suspicion when managing hypertension that is difficult to control. Table 9 lists the clinical findings of the major etiologies of secondary hypertension, associating them with the complementary tests that should be used to establish the diagnosis.

Causes and signs of secondary hypertension and diagnostic tests.

| Clinical findings | Diagnostic suspicion | Additional studies |

|---|---|---|

| Snoring, daytime sleepiness, MS | OSAHS | Berlin questionnaire, polysomnography or home respiratory polygraphy with at least 5 episodes of apnea and/or hypopnea per hour of sleep |

| RHTN and/or hypokalemia (optional) and/or adrenal nodule | Primary hyperaldosteronism (adrenal hyperplasia or adenoma) | Measurements of aldosterone (>15 ng/dl) and plasma renin activity/concentration; aldosterone/renin ratio >30 Confirmatory tests with furosemide and captopril Imaging tests: thin-slice CT or MRI |

| Edema, anorexia, fatigue, high creatinine and urea, urine sediment changes | Renal parenchymal disease | Urine analysis, eGFR, renal ultrasound, screening for albuminuria/proteinuria |

| Abdominal murmur, sudden APE, renal function changes due to drugs that block the RAAS | Renovascular disease | Renal Doppler ultrasound and/or renogram, MRI or CT angiography, renal arteriography |

| Absent or decreased femoral pulses, decreased blood pressure in the lower limbs, chest X-ray changes | Aortic coarctation | Echocardiogram and/or chest angiography by CT |

| Weight gain, decreased libido, fatigue, hirsutism, amenorrhea, ‘moon face’, ‘buffalo hump’, purple striae, central obesity, hypokalemia | Cushing's syndrome (hyperplasia, adenoma and excessive production of ACTH) | Salivary cortisol, 24-h urinary free cortisol and suppression test: morning cortisol (8 am) and 8 h after administration of 1 mg dexamethasone at 12 pm; MRI |

| Paroxysmal hypertension with headache, sweating and palpitations | Pheochromocytoma | Free plasma metanephrines, plasma catecholamines and urine metanephrines; CT and MRI |

| Fatigue, weight gain, hair loss, DHTN, muscle weakness | Hypothyroidism (20%) | TSH and free T4 |

| Intolerance to heat, weight loss, palpitations, exophthalmos, hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, tremors, tachycardia | Hyperthyroidism | TSH and free T4 |

| Renal lithiasis, osteoporosis, depression, lethargy, muscle weakness or spasms, thirst, polyuria | Hyperparathyroidism (hyperplasia or adenoma) | Plasma calcium and PTH |

| Headache, fatigue, visual disorders, enlarged hands, feet and tongue | Acromegaly | IGF-1 and GH levels at baseline and during oral glucose tolerance test |

ACTH: adrenocorticotropin; APE: acute pulmonary edema; CT: computed tomography; DHTN: diastolic hypertension; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; GH: growth hormone; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MS: metabolic syndrome; OSAHS: obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome; PTH: parathyroid hormone; RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; RHTN: resistant hypertension; T4: thyroxine; TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone.

Adapted with permission from Malachias et al.1

As in NCDs, lifelong adherence to hypertension treatment is poor; 40% of patients quit regular treatment in the first year, and thus do not benefit from reductions in TOD and cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke. The main factors affecting non-adherence to treatment are adverse effects, number of daily doses and drug tolerance. Fixed drug combinations make adherence to treatment easier, reducing the likelihood of irregularities in daily doses. The involvement of patients and families, as well as a multidisciplinary approach, enhance adherence to treatment. The use of interactive apps that increase patients’ participation in BP control can encourage them to persist in taking their medication regularly.16

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Oliveira GMM, Mendes M, Malachias MVB, et al. Diretrizes de 2017 em Hipertensão Arterial para Cuidados Primários nos Países de Língua Portuguesa. Rev Port Cardiol. 2017;36:789–798.