System delay (time between first medical contact and reperfusion therapy) is an indicator of quality of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients. This study aimed to assess changes in system delay between 2011 and 2015, and to identify its predictors.

MethodsThe study included 838 patients admitted to 18 Portuguese interventional cardiology centers suspected of having STEMI with less than 12 hours’ duration who were referred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Data were collected for a one-month period every year from 2011 to 2015. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine predictors of system delay.

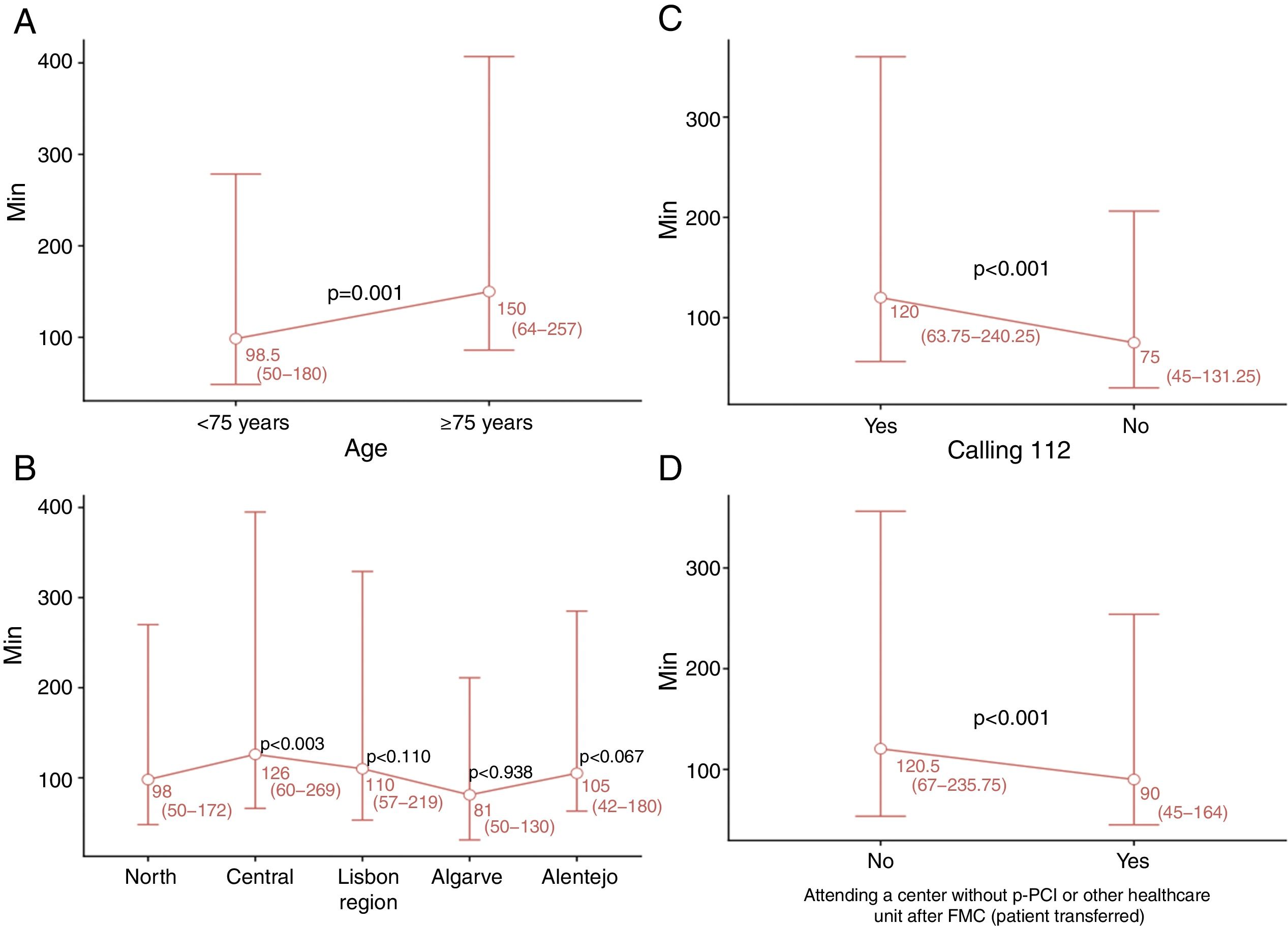

ResultsNo significant changes in system delay were observed during the study. Only 27% of patients had a system delay of ≤90 min. Multivariate analysis identified four predictors of system delay: age ≥75 years (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.50-4.59; p=0.001), attending a center without pPCI (OR 4.08; 95% CI 2.75-6.10; p<0.001), not calling the national medical emergency number (112) (OR 0.47; 95% CI 0.32-0.68; p<0.001), and Central region (OR 3.43; 95% CI 1.60-8.31; p=0.003).

ConclusionsThe factors age ≥75 years, attending a center without pPCI, not calling 112, and Central region were identified as predicting longer system delay. This knowledge may help in planning interventions to reduce system delay and to improve the clinical outcomes of patients with STEMI.

O «Atraso do Sistema» (tempo decorrido entre o primeiro contacto médico e a terapêutica de reperfusão) tem sido considerado um indicador de qualidade na angioplastia primária (P-PCI) em doentes com enfarte do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST (STEMI). Este estudo tem como objetivo estudar a evolução das características do atraso do sistema entre 2011 e 2015 e identificar os seus preditores.

MétodosO estudo incluiu 838 doentes com suspeita de STEMI com menos de 12 horas de evolução e propostos para angioplastia primária, que foram admitidos em 18 centros portugueses de cardiologia de intervenção. Estes dados foram recolhidos durante um mês por ano, entre 2011 e 2015. Modelos de regressão linear univariável e multivariável foram usados para identificar os fatores preditivos do atraso do sistema. Ao longo do estudo, não foram observadas diferenças significativas no atraso do sistema.

ResultadosApenas 27% dos doentes obtiveram um atraso do sistema <90 minutos. A análise multivariável encontrou quatro preditores de atraso do sistema: idade ≥ 75 anos (OR 2,57; CI95% 1,50-4,59; p=0,001), entrada num centro sem P-PCI (OR 4,08; CI95% 2,75-6,10; p<0,001), ligar 112- EMS (OR 0,47; CI95% 0,32-0,68; p<0,001) e Região «Centro» (OR 3,43; CI95% 1,60-8,31; p=0,003).

ConclusõesOs fatores «idade >75 anos», «entrada num centro sem P-PCI», não «ligar para o 112-SEM» e «Região Centro» foram identificados como fatores preditores para maior atraso no sistema. O conhecimento destes fatores permitirá programar intervenções que visem reduzir o atraso do sistema e melhorar os resultados dos doentes com STEMI.

confidence interval

electrocardiogram

emergency medical services

first medical contact

interquartile range

myocardial infarction

odds ratio

primary percutaneous coronary intervention

Stent for Life

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Primary angioplasty is the best treatment for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients.1–4 However, even in the most developed countries, with a national hospital network equipped with catheterization laboratories and highly skilled teams working 24/7, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is rarely achieved within 120 min of symptom onset. Efforts therefore need to be made to enable better access to pPCI. For this purpose, it is essential to audit, monitor and assess coronary networks. Primary angioplasty should be conducted within 12 hours of symptom onset, but the greatest benefits are achieved if pPCI is performed within two hours.1,2,4,5

Total ischemic time, defined as time from symptom onset to reperfusion, is a well-established prognostic factor in STEMI patients.6-9 It is divided into two main periods, time from symptom onset to first medical contact (FMC) (patient delay), and time from FMC to pPCI (system delay).4,10

The guidelines suggest door-to-balloon time (time from arrival at a pPCI center to beginning of pPCI) as a measure to assess the hospital's performance in STEMI treatment.1,4,11 However, other studies have reported that reducing this time does not positively impact mortality11 and that delays at other stages also influence infarct size and mortality in STEMI patients.12,13

Studies have reported that longer system delay is associated with higher mortality and morbidity rates in STEMI patients.7,14–16

Stent for Life (SFL) is an initiative by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions and the European Society of Cardiology designed to improve the treatment of STEMI patients and to reduce STEMI-related mortality. SFL aims to increase the number of STEMI patients treated by pPCI in countries that join the initiative and to ensure that centers are able to perform pPCI 24/7.17 Portugal has been part of this initiative since 201118 and currently 18 centers in mainland Portugal perform pPCI procedures 24/7.

Various factors influence system delay. Importantly, failure to contact the emergency medical services (EMS) and off-hours presentation lead to longer system delay.19

In the last decade, pPCI rates in Portugal were among the lowest in Western Europe, though in recent years the procedure has been performed more frequently in Portuguese hospitals, suggesting that the country's participation in the SFL initiative has had a positive impact.20

This paper aims to assess changes in system delay since Portugal joined SFL, to identify factors that influence this time, and to identify areas of intervention designed to improve care of STEMI patients.

MethodsStudy design and data collectionThe study population was composed of 838 patients suspected of having STEMI with less than 12 hours’ duration who were referred for pPCI and admitted to one of the 18 interventional cardiology centers in mainland Portugal that have 24/7 pPCI and participate in the National Registry of Interventional Cardiology (RNCI) and the Portuguese Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (ProACS). The diagnosis of STEMI was confirmed in 90.5% of cases.

The study was based on a national survey involving these centers under the aegis of the Portuguese Association of Interventional Cardiology (APIC). For a one-month period, every year from 2011 to 2015, all patients with STEMI who underwent coronary angiography at the participating centers were enrolled in the study. The survey was carried out at five time points: from May 9 to June 8, 2011, immediately after Portugal joined SFL (time zero, T0), and at the same point in 2012 (time one, T1), 2013 (time two, T2), 2014 (time three, T3) and 2015 (time four, T4). STEMI was defined according to the universal definition of myocardial infarction.21 FMC was defined as the time of arrival of medical and/or paramedical staff to attend the patient or the time of arrival at a hospital for fibrinolysis or pPCI.

Patients who received fibrinolytic therapy prior to pPCI, presented with in-hospital STEMI, were admitted in the autonomous regions of Madeira and the Azores, had late STEMI presentation (more than 12 hours after symptom onset), or did not present ST elevation on the electrocardiogram, were excluded from the study.

Demographic and clinical data were collected. System delay was considered as a continuous or categorical variable, in accordance with international guidelines. The cut-offs used were 120 min for total ischemic time, 90 min for system delay, 60 min for door-to-balloon time and 10 min for FMC-to-electrocardiogram (ECG) time.

Statistical analysisThe normality of data was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. As system delay values were skewed, they were described using medians and interquartile range (IQR) and tested using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test for two or more independent samples, respectively. Additionally, considering system delay as a categorical variable (≤90 min), number and percentage were used to summarize this variable and differences between groups were assessed by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test.

For categorical data, differences between groups were assessed by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. For continuous and normally distributed data, differences between two or more groups were assessed by the Student's t test or ANOVA, respectively. For non-normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney test or the Kruskal-Wallis test were used.

Considering system delay as a categorical outcome, its association with each potential predictive factor was first tested in a univariate logistic regression model. Multivariate logistic regression models were then used to determine variables independently associated with system delay, considering all significant predictive factors identified in the univariate model. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. The analysis was conducted at a 5% level of significance. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.1.0.22

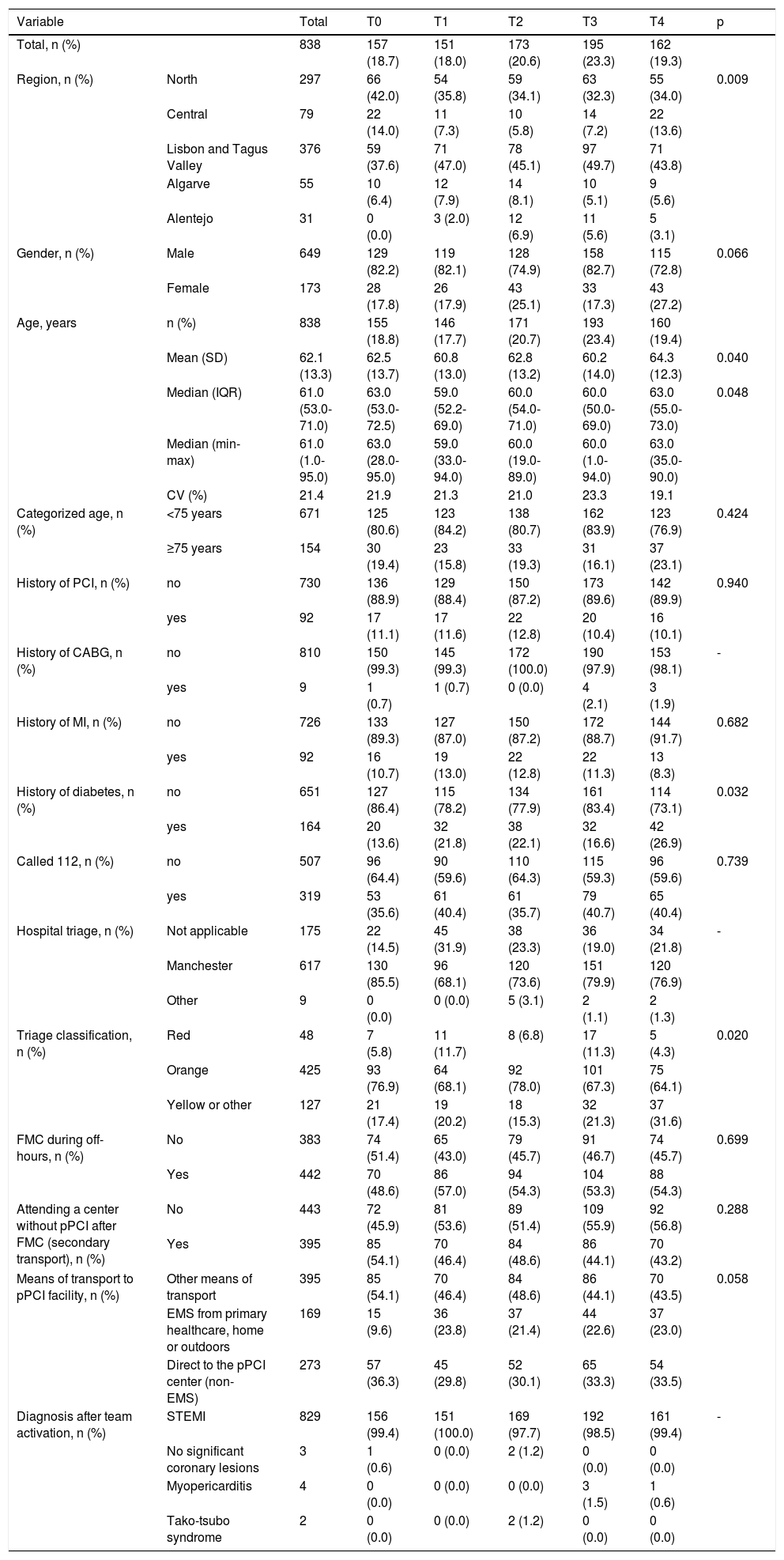

ResultsThe sample comprised 838 patients who underwent pPCI between 2011 (T0) and 2015 (T4). Patient characteristics over the years are summarized in Table 1. In the last year (T4), patients included in the analysis were older (p=0.048) and had a higher prevalence of diabetes compared to previous years (p=0.032). Although the percentage of patients who called the national medical emergency number (112) did not change, the number of patients admitted to a pPCI center through the EMS tended to increase. By contrast, there was a downward trend in the proportion of patients transferred from local hospitals without pPCI facilities. Of the 319 patients with suspected STEMI who called 112, only 169 (53%) were in fact transported by the EMS (Table 1).

Characteristics of the study population at the different time points of the survey.

| Variable | Total | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 838 | 157 (18.7) | 151 (18.0) | 173 (20.6) | 195 (23.3) | 162 (19.3) | ||

| Region, n (%) | North | 297 | 66 (42.0) | 54 (35.8) | 59 (34.1) | 63 (32.3) | 55 (34.0) | 0.009 |

| Central | 79 | 22 (14.0) | 11 (7.3) | 10 (5.8) | 14 (7.2) | 22 (13.6) | ||

| Lisbon and Tagus Valley | 376 | 59 (37.6) | 71 (47.0) | 78 (45.1) | 97 (49.7) | 71 (43.8) | ||

| Algarve | 55 | 10 (6.4) | 12 (7.9) | 14 (8.1) | 10 (5.1) | 9 (5.6) | ||

| Alentejo | 31 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) | 12 (6.9) | 11 (5.6) | 5 (3.1) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | Male | 649 | 129 (82.2) | 119 (82.1) | 128 (74.9) | 158 (82.7) | 115 (72.8) | 0.066 |

| Female | 173 | 28 (17.8) | 26 (17.9) | 43 (25.1) | 33 (17.3) | 43 (27.2) | ||

| Age, years | n (%) | 838 | 155 (18.8) | 146 (17.7) | 171 (20.7) | 193 (23.4) | 160 (19.4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 62.1 (13.3) | 62.5 (13.7) | 60.8 (13.0) | 62.8 (13.2) | 60.2 (14.0) | 64.3 (12.3) | 0.040 | |

| Median (IQR) | 61.0 (53.0-71.0) | 63.0 (53.0-72.5) | 59.0 (52.2-69.0) | 60.0 (54.0-71.0) | 60.0 (50.0-69.0) | 63.0 (55.0-73.0) | 0.048 | |

| Median (min-max) | 61.0 (1.0-95.0) | 63.0 (28.0-95.0) | 59.0 (33.0-94.0) | 60.0 (19.0-89.0) | 60.0 (1.0-94.0) | 63.0 (35.0-90.0) | ||

| CV (%) | 21.4 | 21.9 | 21.3 | 21.0 | 23.3 | 19.1 | ||

| Categorized age, n (%) | <75 years | 671 | 125 (80.6) | 123 (84.2) | 138 (80.7) | 162 (83.9) | 123 (76.9) | 0.424 |

| ≥75 years | 154 | 30 (19.4) | 23 (15.8) | 33 (19.3) | 31 (16.1) | 37 (23.1) | ||

| History of PCI, n (%) | no | 730 | 136 (88.9) | 129 (88.4) | 150 (87.2) | 173 (89.6) | 142 (89.9) | 0.940 |

| yes | 92 | 17 (11.1) | 17 (11.6) | 22 (12.8) | 20 (10.4) | 16 (10.1) | ||

| History of CABG, n (%) | no | 810 | 150 (99.3) | 145 (99.3) | 172 (100.0) | 190 (97.9) | 153 (98.1) | - |

| yes | 9 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.9) | ||

| History of MI, n (%) | no | 726 | 133 (89.3) | 127 (87.0) | 150 (87.2) | 172 (88.7) | 144 (91.7) | 0.682 |

| yes | 92 | 16 (10.7) | 19 (13.0) | 22 (12.8) | 22 (11.3) | 13 (8.3) | ||

| History of diabetes, n (%) | no | 651 | 127 (86.4) | 115 (78.2) | 134 (77.9) | 161 (83.4) | 114 (73.1) | 0.032 |

| yes | 164 | 20 (13.6) | 32 (21.8) | 38 (22.1) | 32 (16.6) | 42 (26.9) | ||

| Called 112, n (%) | no | 507 | 96 (64.4) | 90 (59.6) | 110 (64.3) | 115 (59.3) | 96 (59.6) | 0.739 |

| yes | 319 | 53 (35.6) | 61 (40.4) | 61 (35.7) | 79 (40.7) | 65 (40.4) | ||

| Hospital triage, n (%) | Not applicable | 175 | 22 (14.5) | 45 (31.9) | 38 (23.3) | 36 (19.0) | 34 (21.8) | - |

| Manchester | 617 | 130 (85.5) | 96 (68.1) | 120 (73.6) | 151 (79.9) | 120 (76.9) | ||

| Other | 9 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.3) | ||

| Triage classification, n (%) | Red | 48 | 7 (5.8) | 11 (11.7) | 8 (6.8) | 17 (11.3) | 5 (4.3) | 0.020 |

| Orange | 425 | 93 (76.9) | 64 (68.1) | 92 (78.0) | 101 (67.3) | 75 (64.1) | ||

| Yellow or other | 127 | 21 (17.4) | 19 (20.2) | 18 (15.3) | 32 (21.3) | 37 (31.6) | ||

| FMC during off-hours, n (%) | No | 383 | 74 (51.4) | 65 (43.0) | 79 (45.7) | 91 (46.7) | 74 (45.7) | 0.699 |

| Yes | 442 | 70 (48.6) | 86 (57.0) | 94 (54.3) | 104 (53.3) | 88 (54.3) | ||

| Attending a center without pPCI after FMC (secondary transport), n (%) | No | 443 | 72 (45.9) | 81 (53.6) | 89 (51.4) | 109 (55.9) | 92 (56.8) | 0.288 |

| Yes | 395 | 85 (54.1) | 70 (46.4) | 84 (48.6) | 86 (44.1) | 70 (43.2) | ||

| Means of transport to pPCI facility, n (%) | Other means of transport | 395 | 85 (54.1) | 70 (46.4) | 84 (48.6) | 86 (44.1) | 70 (43.5) | 0.058 |

| EMS from primary healthcare, home or outdoors | 169 | 15 (9.6) | 36 (23.8) | 37 (21.4) | 44 (22.6) | 37 (23.0) | ||

| Direct to the pPCI center (non-EMS) | 273 | 57 (36.3) | 45 (29.8) | 52 (30.1) | 65 (33.3) | 54 (33.5) | ||

| Diagnosis after team activation, n (%) | STEMI | 829 | 156 (99.4) | 151 (100.0) | 169 (97.7) | 192 (98.5) | 161 (99.4) | - |

| No significant coronary lesions | 3 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Myopericarditis | 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Tako-tsubo syndrome | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

p: for difference between groups using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test.

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CV: coefficient of variation; ECG: electrocardiogram; EMS: emergency medical services; FMC: first medical contact; IQR: interquartile range; MI: myocardial infarction; min-max: minimum-maximum; pPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; T0: time zero, 2011; T1: time one, 2012; T2: time two, 2013; T3: time three, 2014; T4: time four, 2015.

Considering only the patients transferred (n=379), there were differences between the time points in those transferred by EMS from another hospital to the pPCI center (inter-hospital transport: 21% vs. secondary transport: 79%) (p<0.001). The percentage of patients using secondary transport decreased throughout the survey (data not shown).

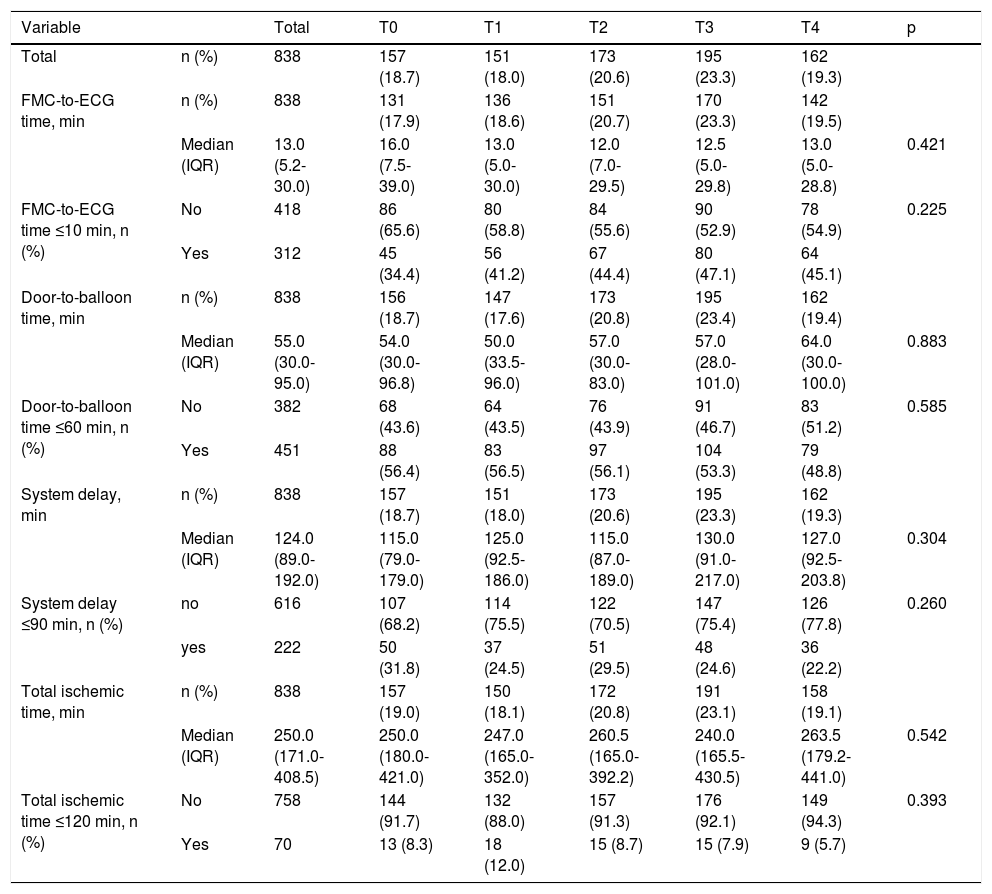

Table 2 presents the characteristics of system delay (FMC-to-ECG time, door-to-balloon time, system delay and total ischemic time) for the different time points. No differences were found between the four time points. The percentage of patients with FMC-to-ECG time <10 min was less than 50% at all time points. Door-to-balloon time <60 min decreased non-significantly from 56.4% to 48.8%. Two hundred and twenty-two patients (26%) had a system delay of ≤90 min and only 70 patients (8%) had total ischemic time of ≤120 min.

Characterization of system delay and other times that influence system delay over the different time points of the survey.

| Variable | Total | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | n (%) | 838 | 157 (18.7) | 151 (18.0) | 173 (20.6) | 195 (23.3) | 162 (19.3) | |

| FMC-to-ECG time, min | n (%) | 838 | 131 (17.9) | 136 (18.6) | 151 (20.7) | 170 (23.3) | 142 (19.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 13.0 (5.2-30.0) | 16.0 (7.5-39.0) | 13.0 (5.0-30.0) | 12.0 (7.0-29.5) | 12.5 (5.0-29.8) | 13.0 (5.0-28.8) | 0.421 | |

| FMC-to-ECG time ≤10 min, n (%) | No | 418 | 86 (65.6) | 80 (58.8) | 84 (55.6) | 90 (52.9) | 78 (54.9) | 0.225 |

| Yes | 312 | 45 (34.4) | 56 (41.2) | 67 (44.4) | 80 (47.1) | 64 (45.1) | ||

| Door-to-balloon time, min | n (%) | 838 | 156 (18.7) | 147 (17.6) | 173 (20.8) | 195 (23.4) | 162 (19.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 55.0 (30.0-95.0) | 54.0 (30.0-96.8) | 50.0 (33.5-96.0) | 57.0 (30.0-83.0) | 57.0 (28.0-101.0) | 64.0 (30.0-100.0) | 0.883 | |

| Door-to-balloon time ≤60 min, n (%) | No | 382 | 68 (43.6) | 64 (43.5) | 76 (43.9) | 91 (46.7) | 83 (51.2) | 0.585 |

| Yes | 451 | 88 (56.4) | 83 (56.5) | 97 (56.1) | 104 (53.3) | 79 (48.8) | ||

| System delay, min | n (%) | 838 | 157 (18.7) | 151 (18.0) | 173 (20.6) | 195 (23.3) | 162 (19.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 124.0 (89.0-192.0) | 115.0 (79.0-179.0) | 125.0 (92.5-186.0) | 115.0 (87.0-189.0) | 130.0 (91.0-217.0) | 127.0 (92.5-203.8) | 0.304 | |

| System delay ≤90 min, n (%) | no | 616 | 107 (68.2) | 114 (75.5) | 122 (70.5) | 147 (75.4) | 126 (77.8) | 0.260 |

| yes | 222 | 50 (31.8) | 37 (24.5) | 51 (29.5) | 48 (24.6) | 36 (22.2) | ||

| Total ischemic time, min | n (%) | 838 | 157 (19.0) | 150 (18.1) | 172 (20.8) | 191 (23.1) | 158 (19.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 250.0 (171.0-408.5) | 250.0 (180.0-421.0) | 247.0 (165.0-352.0) | 260.5 (165.0-392.2) | 240.0 (165.5-430.5) | 263.5 (179.2-441.0) | 0.542 | |

| Total ischemic time ≤120 min, n (%) | No | 758 | 144 (91.7) | 132 (88.0) | 157 (91.3) | 176 (92.1) | 149 (94.3) | 0.393 |

| Yes | 70 | 13 (8.3) | 18 (12.0) | 15 (8.7) | 15 (7.9) | 9 (5.7) |

p: for difference between groups using a non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis).

Door-to-balloon time: time from arrival at a primary percutaneous coronary intervention center to beginning of procedure; ECG: electrocardiogram; FMC: first medical contact; IQR: interquartile range; System delay: time between first medical contact and reperfusion therapy; T0: time zero, 2011; T1: time one, 2012; T2: time two, 2013; T3: time three, 2014; T4: time four, 2015; Total ischemic time: time from symptom onset to reperfusion.

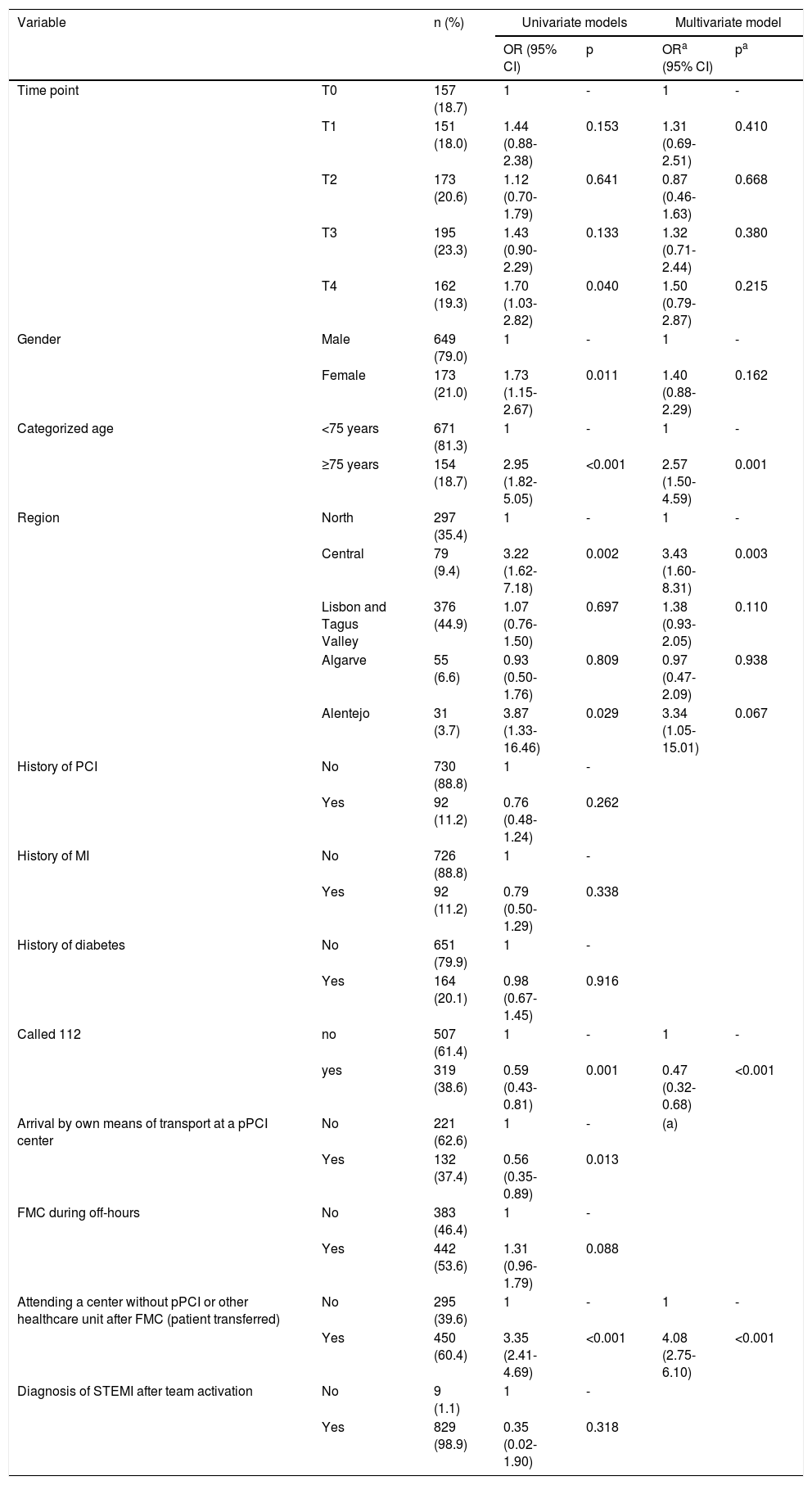

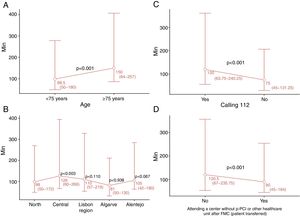

To identify potential factors predicting system delay, univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to analyze a set of variables that could influence the outcome (Table 3). The variables T4, female gender, age ≥75 years, Central and Alentejo regions, not calling 112, not arriving by their own means of transport to a pPCI unit, and attending a center without pPCI or other healthcare unit after FMC (patient transferred) were identified as potential factors predicting longer system delay in univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Admission during off-hours periods (nights or weekends) was not significantly associated with longer system delay. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only age ≥75 years, Central region, not calling 112 and attending a center without pPCI remained statistically significant predictors of longer system delay. Medians and interquartile range of system delay are presented in Figure 1 for each category of these predictive factors with p-values from multivariate logistic regression.

Univariate and multivariate log-linear regression analysis of predictors of system delay.

| Variable | n (%) | Univariate models | Multivariate model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | ORa (95% CI) | pa | |||

| Time point | T0 | 157 (18.7) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| T1 | 151 (18.0) | 1.44 (0.88-2.38) | 0.153 | 1.31 (0.69-2.51) | 0.410 | |

| T2 | 173 (20.6) | 1.12 (0.70-1.79) | 0.641 | 0.87 (0.46-1.63) | 0.668 | |

| T3 | 195 (23.3) | 1.43 (0.90-2.29) | 0.133 | 1.32 (0.71-2.44) | 0.380 | |

| T4 | 162 (19.3) | 1.70 (1.03-2.82) | 0.040 | 1.50 (0.79-2.87) | 0.215 | |

| Gender | Male | 649 (79.0) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Female | 173 (21.0) | 1.73 (1.15-2.67) | 0.011 | 1.40 (0.88-2.29) | 0.162 | |

| Categorized age | <75 years | 671 (81.3) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| ≥75 years | 154 (18.7) | 2.95 (1.82-5.05) | <0.001 | 2.57 (1.50-4.59) | 0.001 | |

| Region | North | 297 (35.4) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Central | 79 (9.4) | 3.22 (1.62-7.18) | 0.002 | 3.43 (1.60-8.31) | 0.003 | |

| Lisbon and Tagus Valley | 376 (44.9) | 1.07 (0.76-1.50) | 0.697 | 1.38 (0.93-2.05) | 0.110 | |

| Algarve | 55 (6.6) | 0.93 (0.50-1.76) | 0.809 | 0.97 (0.47-2.09) | 0.938 | |

| Alentejo | 31 (3.7) | 3.87 (1.33-16.46) | 0.029 | 3.34 (1.05-15.01) | 0.067 | |

| History of PCI | No | 730 (88.8) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 92 (11.2) | 0.76 (0.48-1.24) | 0.262 | |||

| History of MI | No | 726 (88.8) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 92 (11.2) | 0.79 (0.50-1.29) | 0.338 | |||

| History of diabetes | No | 651 (79.9) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 164 (20.1) | 0.98 (0.67-1.45) | 0.916 | |||

| Called 112 | no | 507 (61.4) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| yes | 319 (38.6) | 0.59 (0.43-0.81) | 0.001 | 0.47 (0.32-0.68) | <0.001 | |

| Arrival by own means of transport at a pPCI center | No | 221 (62.6) | 1 | - | (a) | |

| Yes | 132 (37.4) | 0.56 (0.35-0.89) | 0.013 | |||

| FMC during off-hours | No | 383 (46.4) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 442 (53.6) | 1.31 (0.96-1.79) | 0.088 | |||

| Attending a center without pPCI or other healthcare unit after FMC (patient transferred) | No | 295 (39.6) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 450 (60.4) | 3.35 (2.41-4.69) | <0.001 | 4.08 (2.75-6.10) | <0.001 | |

| Diagnosis of STEMI after team activation | No | 9 (1.1) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 829 (98.9) | 0.35 (0.02-1.90) | 0.318 | |||

Adjusted for all the other covariates presented in the multivariate model.

CI: confidence interval; FMC: first medical contact; MI: myocardial infarction; OR: odds ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention; T0: time zero, 2011; T1: time one, 2012; T2: time two, 2013; T3: time three, 2014; T4: time four, 2015.

Only significant variables were included in the multivariate model (except variables with problems of multicollinearity). The variable history of coronary artery bypass grafting was not included because the small number of cases.

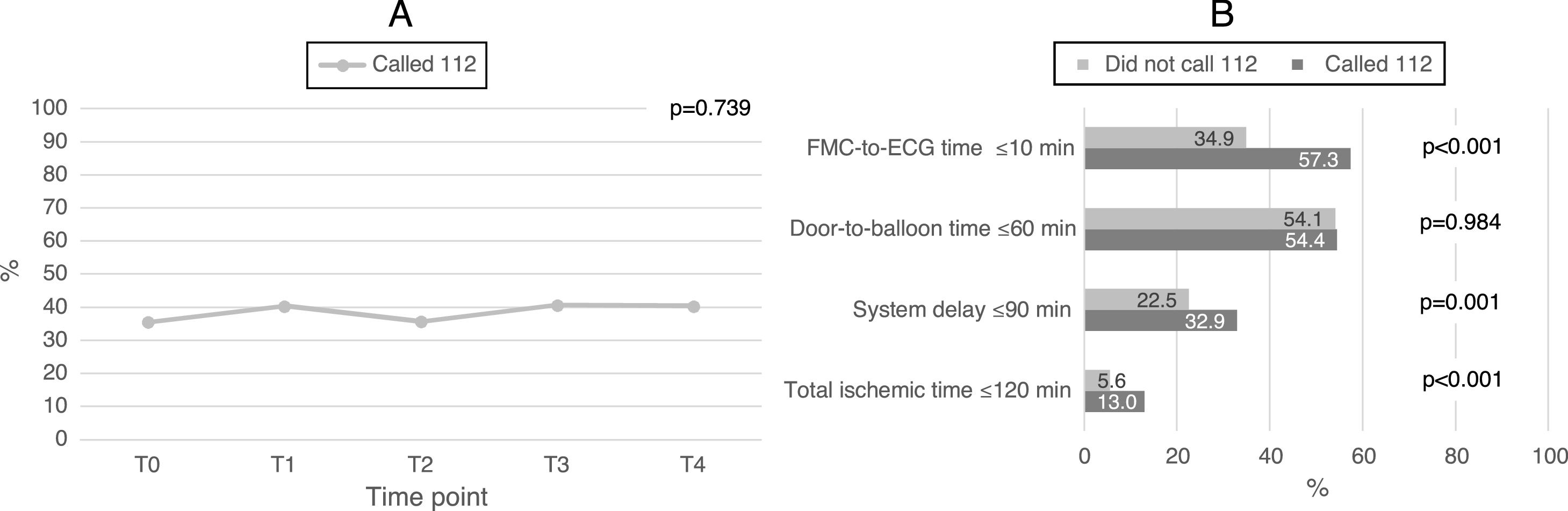

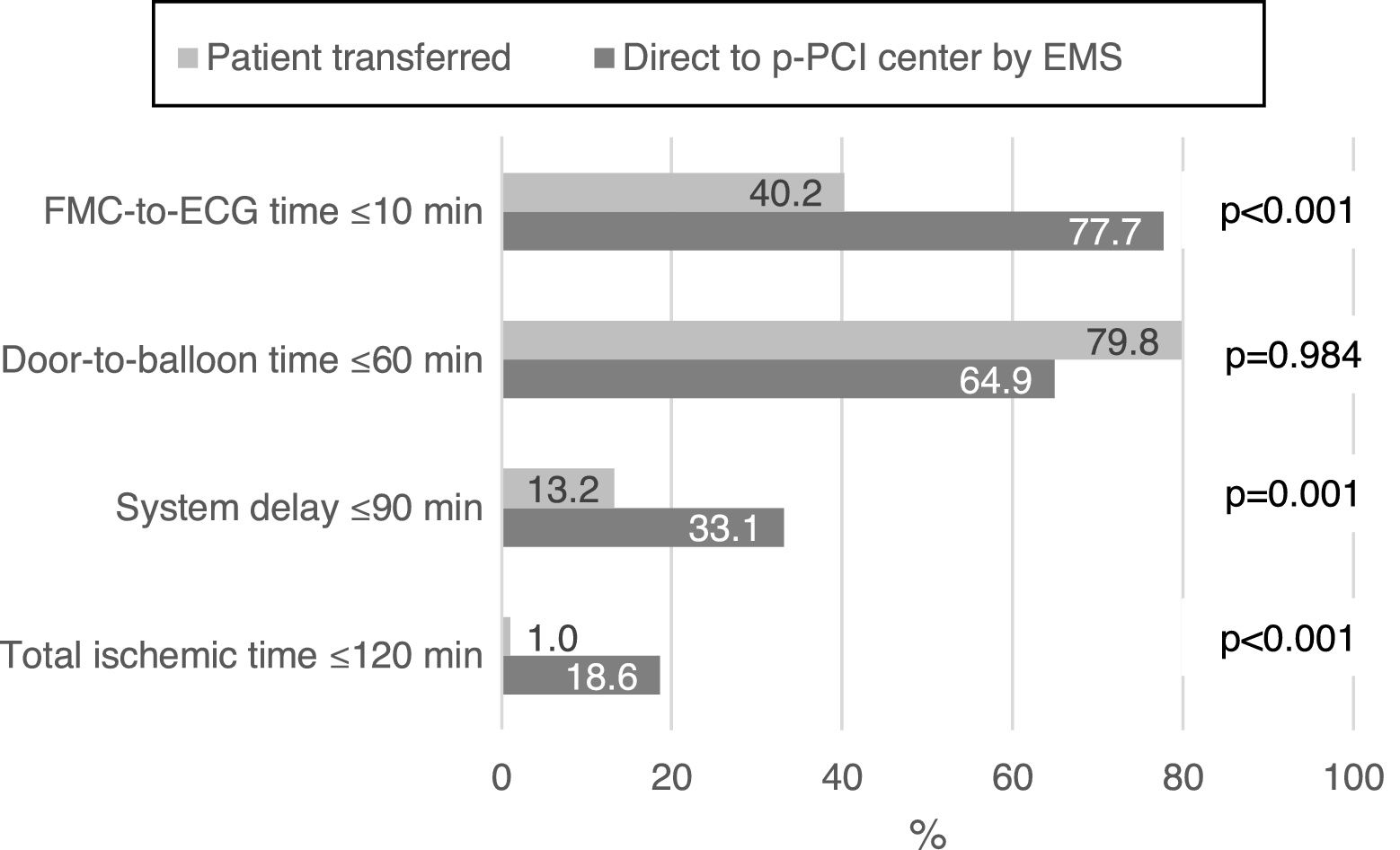

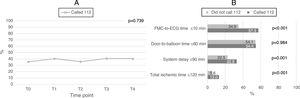

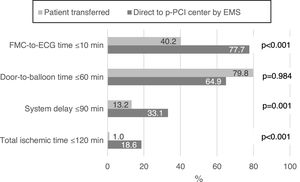

Figure 2A shows that there were no significant changes in the number of patients calling 112 over the different time points of the survey (T0-T4) (p=0.739). When stratified according to whether or not patients called 112 (Figure 2B), differences between the groups were found for FMC-to-ECG time (p<0.001), system delay (p=0.001) and total ischemic time (p<0.001). It can also be seen that 32.9% of patients calling 112 had a system delay ≤90 min, which is significantly more than those who did not (22.5%). Similarly, considering as a variable whether the patient was transferred or was taken direct to the pPCI center by the EMS, differences were found for FMC-to-ECG time, system delay and total ischemic time (Figure 3). It can be seen that 33.1% of patients transported directly to a pPCI center by the EMS had a system delay ≤90 min vs. 13.2% of patients who were transferred (p=0.001), which corresponds to 20% more patients who were within the recommended system delay times.

(A) Changes in numbers of patients calling for the different time points of the survey; (B) differences in system delay between patients who called and did not call 112. ECG: electrocardiogram; FMC: first medical contact; T0: time zero, 2011; T1: time one, 2012; T2: time two, 2013; T3: time three, 2014; T4: time four, 2015.

System delay is one of the most important timings for assessing the quality of a system, but also for determining which reperfusion strategy should be used.23 Current guidelines suggest pPCI as the ideal reperfusion strategy in STEMI patients, unless it cannot be offered within the recommended timeframes, in which case fibrinolytic therapy should be considered. There is, however, still considerable debate concerning how much delay is acceptable when making this decision, or when a combination of the two reperfusion methods should be preferred.24,25 There is evidence that pPCI loses its advantage over fibrinolysis for longer delays after symptom onset.26

Our results suggest that there were no significant improvements in system delay between the beginning of SFL in Portugal (T0) and 2015 (T4). Furthermore, the study suggests that the aims stated in the current STEMI treatment guidelines1,2 have not been achieved in Portugal: system delay was over 115 min at all the time points of the study, and only 33.1% of STEMI patients transported directly to a pPCI center by EMS had a system delay of 90 min or less. The situation is very different in central and northern Europe. In daily practice in the Netherlands, almost all STEMI patients can be transported to a pPCI center within 60 min of FMC (which is usually the emergency call),27 while in Sweden the median FMC-pPCI time is 70 min.28

Univariate analysis of our results revealed that six factors influence system delay: age ≥75 years, female gender, Central and Alentejo regions, and attending a center without pPCI were associated with longer system delay, whereas the variables calling 112 and arrival by their own means of transport at a pPCI center were associated with shorter system delay. However, the multivariate model showed that only the variables age ≥75 years, Central region, and attending a center without pPCI were predictors of longer system delay, whereas calling 112 was predictive of shorter system delay.

In view of these results, it is important to look at the way elderly patients are handled when they enter the health system. This segment of the population presents specific characteristics that contribute to greater system delay. Low literacy levels, slowness and frailty affect how these patients are handled and transported in and between hospitals, leading to further delays.

The Central region presents significantly longer system delays than other regions of the country. One of the reasons for this result may be the greater distances in this region between the patient's location at the time of symptom onset and the pPCI center. Geographic adjustments in the STEMI network and improvements in transport (direct to a pPCI center and transfer) may lead to more equitable access to pPCI.

The fact that there were more patients who called 112 with system delay ≤90 min than those who did not may have a simple explanation: in the former group, the number of patients who arrive directly at a pPCI center and who spend no time in inter-hospital transfer is likely to be much higher. The fact that in our study patients who called 112 had significantly shorter system delay may be closely related to the SFL initiative in Portugal, as since the beginning of this initiative, the EMS started to contact pPCI centers directly, to transmit ECGs wirelessly, and to deliver STEMI patients directly to catheterization laboratories. This is confirmed by the fact that, in this study, more patients transported by the EMS had an FMC-to-ECG time of ≤10 min than those not transferred by the EMS. A recent study in the USA demonstrated that prehospital wireless electrocardiogram transmission reduced system delay.29 In Denmark, a study conducted between 1999 and 2009 investigated the impact of a gradual introduction of field triage for pPCI and associated outcomes. Among patients transported by the EMS from the scene of the event, the proportion who were triaged directly to a pPCI center in the field increased from 33% to 72%.30 Current guidelines confirm the importance of field triage, stating that the delay between FMC and diagnosis should be reduced to 10 min or less.1

In our study, STEMI patients who initially attended a center without pPCI had significantly longer system delay than those who arrived directly at a pPCI center. Comparison of the variables patient transferred vs. direct to pPCI center by EMS, as they relate to FMC-to-ECG time ≤10 min, system delay ≤90 min, and total ischemic time ≤120 min, suggests that attending a center without pPCI is a strong predictor of prolonged system delay. Significantly more patients transported directly to a pPCI center by the EMS had a system delay of ≤90 min. In the worst-case scenario (patient transferred), prolonged delay is closely related to time spent in the first hospital (door-in-door-out) and with inter-hospital transfer. Some studies suggest that door-in-door-out time is associated with patient management in the emergency room of the non-pPCI hospital.16,31

Although information campaigns to raise awareness of MI have been conducted, many patients still do not call the EMS and arrive at the hospital by their own means.5 However, in some cases admission to a center without pPCI may be through the EMS. This does not always imply a system failure; one study suggested that these delays are often due to diagnostic uncertainty instead. Of patients with suspected STEMI who called 112, only 53% were in fact transported by an EMS ambulance. In the other cases, the national referral center for emergency patients (CODU) did not activate EMS transportation for two main reasons: there were no EMS vehicles available, or the patients were misdiagnosed. In both cases, the patients were transported by the fire department and not by EMS ambulance, as should have occurred. In a Canadian study, patients requiring pPCI and undergoing inter-hospital transfer had longer symptom-call times, lower ECG ST-elevation scores, and more protocol-negative ECGs at presentation.32

Regarding transferred patients, our results suggest a positive trend, with a significant decrease being observed over the course of the study. Nevertheless, there are some actions that can still be implemented to improve the outcomes of transferred patients, as suggested in a five-year study in the USA, in which a program of rapid triage, transfer, and treatment of STEMI patients implemented in a rural area reduced in-hospital mortality and produced progressive improvements in door-to-balloon time.33

Raising public awareness, including strengthening and improving campaigns to publicize the onset of MI symptoms and to encourage people to call the 112 emergency number, could help reduce system delay.

Our results indicate that system delay did not decrease over the course of the SFL initiative, but this does not mean that the initiative was unsuccessful. Over little more than a decade, the use of pPCI tripled in Portugal.34 The first centers to perform pPCI were located in the largest urban centers, which were provided with more than one angiography room. In these urban centers, secondary transport was practically non-existent and few patients called 112. Thus, system delay was estimated on the basis of door-to-balloon time only. The spread of pPCI to peripheral centers and more frequent 112 calls led to an increase in system delay, mainly due to increased use of secondary transport. At the same time, primary transport by EMS also increased, which also increased system delay. In fact, although the system has become more efficient, the clock now starts ticking as soon as FMC occurs, before arrival at the hospital.

In the intermediate stage of such an initiative, while the system is still adapting and expanding, conventional quality indicators such as patient delay, system delay and door-to-balloon time are not sufficiently sensitive to assess how the initiative is developing. The percentages of patients who call 112, who go directly to secondary hospitals and who are transported by EMS may be more sensitive and earlier indicators that can be used to measure a positive evolution.

Our study has some limitations. Data were only collected on patients treated by pPCI, so they cannot be generalized to all STEMI patients. In addition, the survey only covered one month in each year, which means the possible effects of seasonal factors on the results were not addressed. For this reason, future surveys should collect data continuously.

In conclusion, this study showed that system delay did not change significantly during the study period. However, it revealed that the variables age ≥75 years, attending a center without pPCI, and Central region were significantly associated with prolonged system delay, whereas calling 112 was clearly associated with shorter system delay. Based on these factors, objective measures can be taken to reduce system delay and to improve clinical outcomes in Portuguese STEMI patients. However, efforts to improve outcome should not simply address a single quality measurement but should instead embrace a broader spectrum of procedures in MI care.

Centers participating in the Stent for Life Initiative Portugal under the aegis of the Portuguese Association of Interventional Cardiology (APIC):Hospital Vila Real (Dr. Henrique Cyrne Carvalho and Paulino Sousa), Hospital Braga (Dr. João Costa), Hospital S. João (Dr. João Carlos Silva), Hospital Santo António (Dr. Henrique Cyrne Carvalho), Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia (Dr. Vasco Gama Fernandes), Hospital de Viseu (Dr. João Pipa), Centro Hospitalar de Coimbra (Dr. Marco Costa and Dr. Vitor Matos), Hospital de Leiria (Dr. João Morais), Hospital Fernando da Fonseca (Dr. Pedro Farto e Abreu), Hospital de Santa Maria (Dr. Pedro Canas da Silva), Hospital Santa Cruz (Dr. Manuel Almeida), Hospital de Santa Marta (Dr. Rui Ferreira), Hospital Curry Cabral (Dr. Luis Morão), Hospital Pulido Valente (Dr. Pedro Cardoso), Hospital Garcia de Orta (Dr. Hélder Pereira), Hospital Setúbal (Dr. Ricardo Santos); Hospital de Évora (Dr. Lino Patrício and Dr. Renato Fernandes), Hospital de Faro (Dr. Victor Brandão).

FundingThe authors state that they have no funding to declare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors gratefully acknowledge all centers that participated in the Stent for Life Initiative Portugal between 2011 and 2015.

pPCI or other healthcare unit after

pPCI or other healthcare unit after  ECG: electrocardiogram;

ECG: electrocardiogram;  pPCI center by the

pPCI center by the