We report the case of a female patient under oral prednisolone therapy due to a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension with papilledema. Unfortunately, short-term treatment with prednisolone caused an unusual complication in the patient, i.e., recurrent myocardial ischemia. Possible mechanisms leading to this complication were evaluated in the light of current knowledge.

Descrevemos o caso clínico de um paciente sob terapia prednisolona oral devido a um diagnóstico de hipertensão intracraniana idiopática com papiledema. Infelizmente, o tratamento a curto prazo com prednisolona causou uma complicação incomum no paciente, isto é, isquemia miocárdica recorrente. Os possíveis mecanismos que conduzem a esta complicação foram avaliados em função das literaturas correntes.

Glucocorticoids not only promote cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia and obesity, but also have direct effects on the heart and blood vessels, influencing vascular function.1 Here we describe a female patient under oral prednisolone therapy due to a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension with papilledema. Unfortunately, short-term treatment with prednisolone caused an unusual complication in the patient, i.e., recurrent myocardial ischemia.

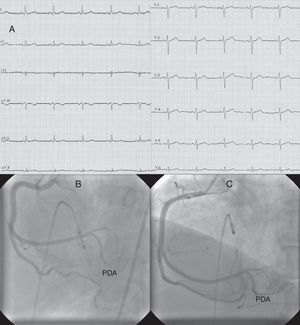

Case reportA 64-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia had recurrent episodes of anginal chest pain at rest and with exertion within one month of starting oral prednisolone (40 mg/day). Her chest pain was not resolved by oral nitroglycerine. The resting electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm and revealed no ischemic changes (Figure 1A). Diagnostic coronary angiography (CAG) showed no obstructive atherosclerotic lesions, but slow flow was present in the right coronary artery (RCA). She was discharged from the hospital medicated with aspirin (100 mg/day) and diltiazem (90 mg/day).

(A) ECG at first admission; (B) right coronary angiography during first myocardial infarction showing total occlusion of the mid portion of the posterior descending artery (PDA); (C) right coronary angiography during first myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention to the PDA.

Two weeks after the first admission, she was again admitted to the emergency department with severe anginal chest pain. The ECG showed nodal rhythm with a heart rate of 40 bpm, ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF and ST-segment depression in leads I and aVL. She was urgently transferred to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. This time, interestingly, CAG showed that the mid portion of the posterior descending artery (PDA) of the RCA was totally occluded (Figure 1B). When a floppy guidewire was passed from the totally occluded PDA, the thrombus moved distally and TIMI III flow was obtained (Figure 1C). At follow-up in the intensive care unit, the ECG returned to sinus rhythm with resolution of the ST segment changes. Pathological Q waves did not develop, but troponin I was elevated at 12 ng/ml (reference: 0–0.2 ng/ml).

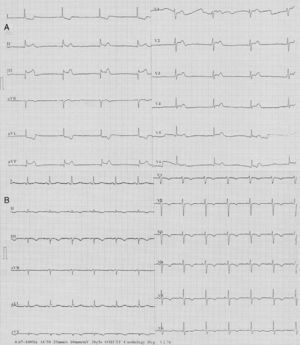

Four days after myocardial infarction (MI), the patient again suffered from severe anginal chest pain. The ECG revealed similar abnormalities to those of four days previously (i.e., nodal rhythm, ST-segment elevation in leads II, III and aVF, and ST-segment depression in leads I and aVL) (Figure 2A). With intravenous atropine (1 mg) and isotonic saline infusion, sinus rhythm was restored and blood pressure was normalized. CAG showed that the PDA was open. But this time, there was slow flow in the left anterior descending coronary artery. At follow-up, the ECG showed pathological Q waves and T-wave inversions in leads II, III, and aVF. Additionally, T-wave inversions developed in the anterior precordial leads (Figure 2B). Troponin I was elevated at 41 ng/ml. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed wall motion abnormalities in the left ventricular inferior and posterior walls. There was no thrombus in the cardiac chambers and the interatrial septum was intact, without passage of agitated saline. There was no abnormal mass related to the heart valves and blood tests revealed no coagulation disorder.

The possibility was raised that the patient's recurrent myocardial ischemia might be related to her steroid use. Therefore, after neurology consultation, oral prednisolone was stopped. She continued to receive oral acetazolamide therapy prescribed previously. After discontinuation of prednisolone, anginal chest pains did not recur. The patient was subsequently discharged from the hospital uneventfully and has remained asymptomatic for one and a half years. After discharge, her cardiovascular medications were aspirin (100 mg/day), clopidogrel (75 mg/day), atorvastatin (40 mg/day) and long-acting nifedipine (30 mg/day).

DiscussionIn this case report, the patient had recurrent episodes of anginal chest pain at rest and with exertion after short-term treatment with oral prednisolone. Although only slow flow was found at the first CAG, she had two consecutive episodes of MI at follow-up. Since anginal chest pain and infarction did not recur after discontinuation of prednisolone, it was thought that the recurrent myocardial ischemia might be related to steroid use. What are the possible pathophysiological explanations for this hypothesis?

It has been shown that high-dose dexamethasone increases soluble P-selectin, a platelet activator, and von Willebrand factor, which is a prothrombotic marker.2 Similarly, short-term dexamethasone use is associated with an increase in clotting factor levels (factors VII, VIII, XI) and fibrinogen.3 Patients with excess cortisol have increased platelet count and tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, but they have decreased plasma tissue factor pathway inhibitor.4 This hypercoagulable and hypofibrinolytic state may increase the risk for atherosclerotic and atherothrombotic complications, as in our patient. The relative risk for the occurrence of a cardiovascular event among patients using high-dose glucocorticoids (≥7.5 mg/day) was 2.56.5 Similarly, another study showed increased risk of acute myocardial infarction with corticosteroid use, with a greater risk observed among users of high doses (>10 mg/day).6 Our patient was taking oral prednisolone 40 mg/day.

Coronary spasm may be induced by corticosteroids. It has been reported that nitrate, nitrite and nitric oxide release is decreased by cortisol treatment in a dose-dependent manner due to decreased ATP-induced intracellular calcium mobilization.7 Additionally, endothelial nitric oxide synthase degradation is increased, leading to decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein levels.7 Glucocorticoids reduce endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability,8 inhibit the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin, an important cofactor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase,9 and suppress the production of the vasodilator prostacyclin by downregulating cyclooxygenase-1 gene expression.10 On the other hand, they increase the synthesis of the vasoconstrictor thromboxane.11 Sustained elevation of serum cortisol levels might lead to sensitization of coronary vasoconstricting responses through Rho-kinase activation,12 while oral cortisol administration impairs cholinergic vasodilation even in healthy normotensive subjects.13 All these mechanisms may reduce coronary blood flow by increasing contraction of coronary arteries. There are a few case reports in the literature reporting the occurrence of coronary spasm following corticosteroid administration.14

Short-term use of oral prednisolone in our patient may have led to endothelial dysfunction, increased microvascular resistance, coronary vasospasm, reduced coronary flow reserve, coronary slow flow, increased thrombogenicity, and eventually recurrent myocardial ischemia.

ConclusionDrugs containing steroids have many side effects involving the cardiovascular system. It should be borne in mind that their use may trigger recurrent myocardial ischemia in some patients.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.