Infection remains a major complication among heart transplant (HT) recipients, causing approximately 20% of deaths in the first year after transplantation. In this population, Aspergillus spp. can have various clinical presentations including invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), with high mortality (53-78%).

ObjectivesTo establish the characteristics of IPA infection in HT recipients and their outcomes in our center.

MethodsAmong 328 HTs performed in our center between 1998 and 2016, we identified five cases of IPA. Patient medical records were examined and clinical variables were extracted.

ResultsAll cases were male, and mean age was 62 years. The most common indication for HT was non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Productive cough was reported as the main symptom. The radiological assessment was based on chest X-ray and chest computed tomography. The most commonly reported radiographic abnormality was multiple nodular opacities in both techniques. Bronchoscopy was performed in all patients and Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated in four cases on bronchoalveolar lavage culture. Treatment included amphotericin in four patients, subsequently changed to voriconazole in three, and posaconazole in one patient, with total treatment lasting an average of 12 months. Neutropenia was found in only one patient, renal failure was observed in two patients, and concurrent cytomegalovirus infection in three patients. All patients were alive after a mean follow-up of 18 months.

ConclusionsIPA is a potentially lethal complication after HT. Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of aggressive treatment are the cornerstone of better survival.

A infeção continua a ser uma complicação major nos recipientes para transplante cardíaco (TC), causando cerca de 20% de mortes no primeiro ano após o transplante. Nestes doentes, o Aspergillus species pode levar a várias apresentações clínicas incluindo a aspergilose pulmonar invasiva (API), com uma mortalidade elevada (53% a 78%).

ObjetivosEstabelecer as características da infeção por API nos recipientes para TC e os respetivos resultados no nosso serviço.

MétodosDos 328 transplantes cardíacos realizados no nosso centro entre 1998 e 2016, identificámos cinco casos de API. Foram examinados os registos dos doentes e foram identificadas variáveis clínicas.

ResultadosEm todos os casos os doentes eram do sexo masculino com idade média de 62 anos. A indicação mais comum para TC foi a miocardiopatia não isquémica dilatada. O principal sintoma foi tosse produtiva. A avaliação radiológica baseou-se na radiografia e na TAC torácicas. A alteração radiológica mais comum foi a densidade nodular múltipla em ambas as técnicas. A broncoscopia foi realizada em todos os doentes e o Aspergillus fumigatus foi isolado em quatro casos de cultura BAL. O tratamento incluiu anfotericina em quatro doentes com alteração subsequente para voriconazol em três doentes e posaconazol num doente, tendo o tratamento durado uma média de 12 meses. A neutropenia foi encontrada num doente apenas, a insuficiência renal foi observada em dois doentes e a infeção por CMV ocorreu em três doentes. Todos os doentes sobreviveram após seguimento de 18 meses.

ConclusãoA API representa uma complicação potencialmente mortal após o TC. Um diagnóstico precoce e a iniciação de um tratamento rapidamente agressivo constituem a pedra angular para uma melhor sobrevivência.

Infection remains a major complication among transplant recipients, causing approximately 20% of deaths in the first year after transplantation, as well as being a major cause of long-term morbidity and mortality. In solid organs, such as cardiac transplantation, in which immunosuppressants are prescribed indefinitely, physicians and patients perpetually negotiate the delicate balance between the risks of graft rejection and infection.1 In this immunosuppressed population, Aspergillus spp. – an opportunistic pathogen – can cause aggressive infections including sinusitis, tracheobronchitis, pneumonia, necrotizing cellulitis, brain abscess, or disseminated disease. In heart transplant (HT) recipients, Aspergillus spp. has been reported as the most common cause of invasive fungal infection and frequently causes pneumonia2 with a high attributable mortality, ranging from 53% to 78%.3–5 Although invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a serious disease in this population, little is known about its natural history. The aim of this study was to further establish the characteristics of IPA infections and their outcomes in our center.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective chart review of patients who underwent heart transplantation at our center between 1998 and 2016 and who subsequently developed IPA. Cases were identified according to the clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America for IPA6 and the revised EORTC/MSG criteria for defining invasive fungal infection, including IPA.7 The diagnosis was considered definite when the patient had positive histology and culture of a sample obtained from the same site, or negative histology (or not performed) and positive culture results of a sample obtained by protocol-specified invasive techniques such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). A galactomannan index of 1 or higher was regarded as positive and suggested a diagnosis of IPA.

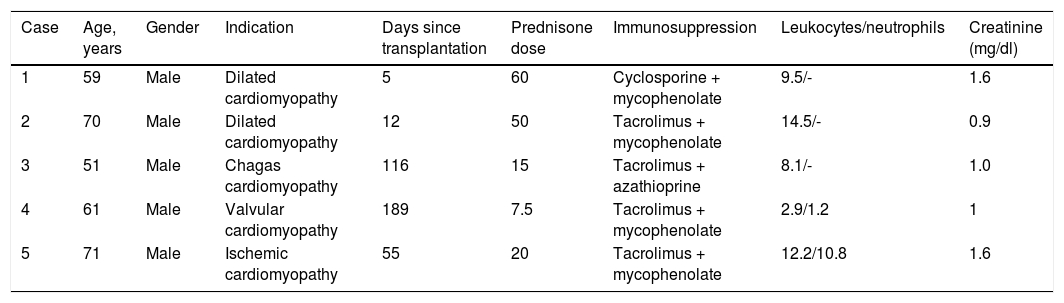

Data collection included age, gender, primary cardiac diagnosis, date of transplantation, immunosuppressant regimen, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serological status, antifungal prophylaxis, known risk factors for IPA (including neutropenia), radiographic features, serum galactomannan level, bronchoscopy and microbiology data (Tables 1 and 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics and laboratory features of the study population.

| Case | Age, years | Gender | Indication | Days since transplantation | Prednisone dose | Immunosuppression | Leukocytes/neutrophils | Creatinine (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59 | Male | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 5 | 60 | Cyclosporine + mycophenolate | 9.5/- | 1.6 |

| 2 | 70 | Male | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 12 | 50 | Tacrolimus + mycophenolate | 14.5/- | 0.9 |

| 3 | 51 | Male | Chagas cardiomyopathy | 116 | 15 | Tacrolimus + azathioprine | 8.1/- | 1.0 |

| 4 | 61 | Male | Valvular cardiomyopathy | 189 | 7.5 | Tacrolimus + mycophenolate | 2.9/1.2 | 1 |

| 5 | 71 | Male | Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 55 | 20 | Tacrolimus + mycophenolate | 12.2/10.8 | 1.6 |

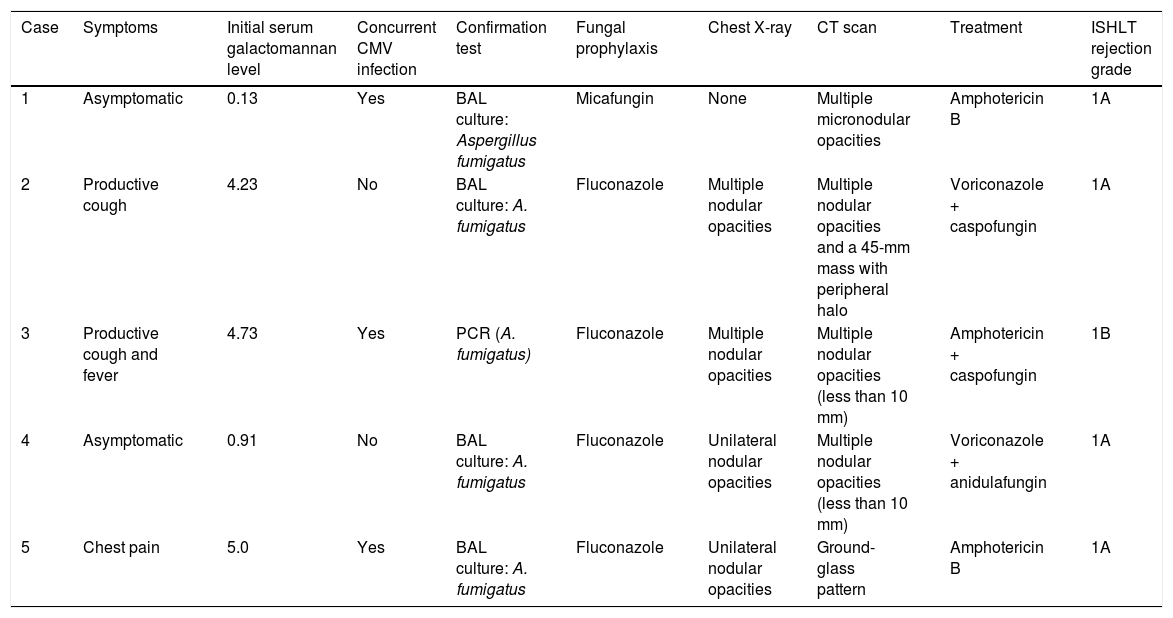

Clinical course and treatment.

| Case | Symptoms | Initial serum galactomannan level | Concurrent CMV infection | Confirmation test | Fungal prophylaxis | Chest X-ray | CT scan | Treatment | ISHLT rejection grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic | 0.13 | Yes | BAL culture: Aspergillus fumigatus | Micafungin | None | Multiple micronodular opacities | Amphotericin B | 1A |

| 2 | Productive cough | 4.23 | No | BAL culture: A. fumigatus | Fluconazole | Multiple nodular opacities | Multiple nodular opacities and a 45-mm mass with peripheral halo | Voriconazole + caspofungin | 1A |

| 3 | Productive cough and fever | 4.73 | Yes | PCR (A. fumigatus) | Fluconazole | Multiple nodular opacities | Multiple nodular opacities (less than 10 mm) | Amphotericin + caspofungin | 1B |

| 4 | Asymptomatic | 0.91 | No | BAL culture: A. fumigatus | Fluconazole | Unilateral nodular opacities | Multiple nodular opacities (less than 10 mm) | Voriconazole + anidulafungin | 1A |

| 5 | Chest pain | 5.0 | Yes | BAL culture: A. fumigatus | Fluconazole | Unilateral nodular opacities | Ground-glass pattern | Amphotericin B | 1A |

BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; CT: computed tomography; ISHLT: International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation.; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

At our institution, by protocol all patients receive induction therapy with basiliximab and high doses of corticosteroids. Basiliximab is administered 4-6hours after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass. Initiation of calcineurin inhibitors is delayed until day 3 post-HT. Maintenance immunosuppressive therapy consists of corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors and cell cycle inhibitors. This immunosuppression regimen is based on the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients.8

In our HT protocol, all patients without risk factors for infection by filamentous fungi are prescribed fluconazole 100mg/day during the first month, from day 1 post-transplant, while patients who are at risk for such infection (at least one of the following risk factors: administration of immunosuppression; acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis; colonization by filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus; retransplant or double transplant [heart and kidney or heart and liver]) receive antifungal prophylaxis with liposomal amphotericin B or micafungin.

In all patients under antifungal prophylaxis, fungal culture and staining with calcium fluoride from sputum or respiratory secretions, chest X-rays and serum galactomannan testing for Aspergillus are performed once a week while hospitalized. If the chest X-ray is doubtful, high-resolution chest computed tomography (CT) is performed.

Following hospital discharge, patients are followed at our center every month for the first six months after HT, every two months from the sixth to the twelfth month, and then every six months indefinitely. At each visit a comprehensive clinical assessment is performed including routine laboratory tests and a chest X-ray.

ResultsAmong 328 HTs performed between 1998 and 2016, we identified five cases of IPA. All cases were male, and mean age was 62 years (range 59-71 years). The most common indication for HT was non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Antifungal prophylaxis was started in all patients, but two patients did not complete the course since IPA was diagnosed in the first 30 days after transplantation. One patient required prophylaxis with micafungin due to acute renal failure.

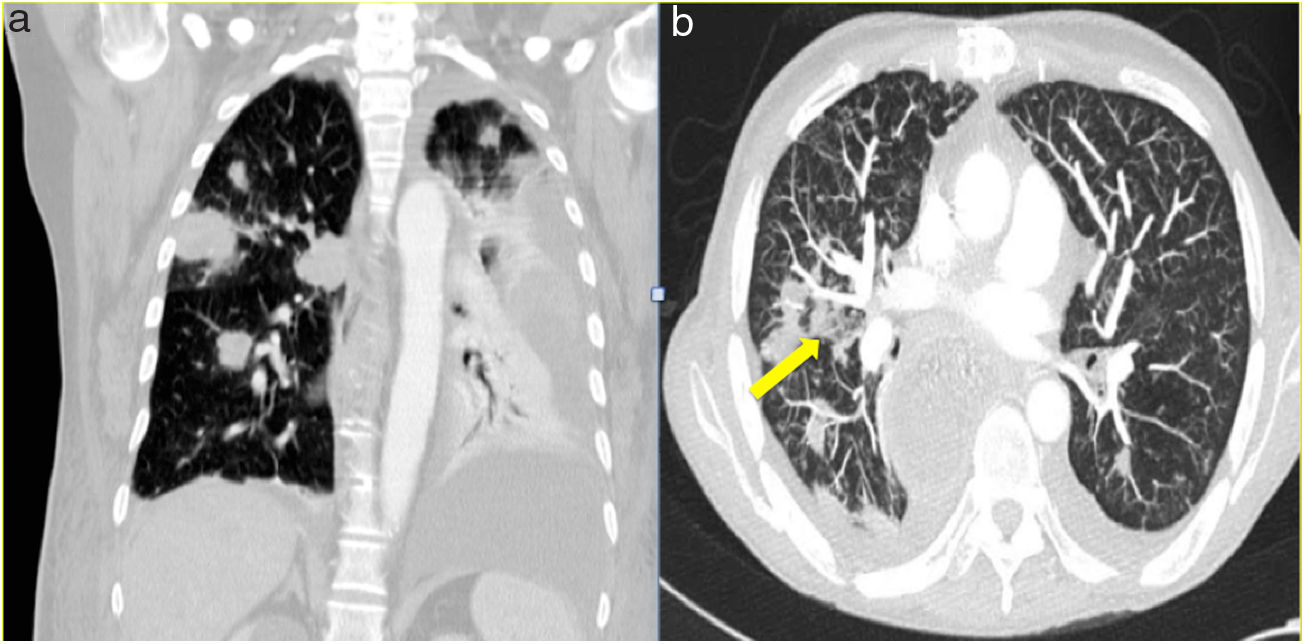

The median time from transplantation to diagnosis was 55 days. Productive cough was reported as the main symptom in two patients, one patient presented atypical chest pain and the other two were asymptomatic. In one of the asymptomatic patients the diagnosis was suspected from abnormal findings (unilateral nodular opacities) on chest X-ray during a routine monthly follow-up visit. In all patients, the radiological assessment was based on chest X-ray and chest CT. The most commonly reported radiographic abnormality was multiple nodular opacities in both imaging techniques (Figure 1). Halo sign was observed in one case (Figure 1B). Serum galactomannan level was abnormally high in three out of five patients. Bronchoscopy was performed in all patients and A. fumigatus was isolated on BAL culture in four cases. Aspergillus was demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the patient in whom nodular lesions on the chest X-ray aroused suspicion of IPA.

Initial antifungal treatment included amphotericin in four patients, subsequently changed to voriconazole in three cases, and posaconazole in one patient, with total treatment lasting an average of 12 months. Two patients required the addition of caspofungin and one of anidulafungin as salvage therapy. Neutropenia was found in only one patient. Renal failure, defined as creatinine >1.5mg/dl, was observed in two patients, and concurrent CMV infection in three patients. All patients were alive after a mean follow-up of 18 months.

DiscussionSince the introduction of HT as a therapeutic modality for end-stage heart failure in 1968, Aspergillus has been recognized as a major opportunistic pathogen with a high attributable mortality.5 Our series of five IPA cases shows unusually low mortality. There are several possible reasons for this. First, the number of reported cases is small; however, 100% survival appears optimistically high, and some fatality would be expected. Second, two patients were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, both with negative serum galactomannan, which indicates that treatment was initiated in good time. Also, four patients received combined treatment with two antifungals and only one patient was treated with just one drug.

The known risk factors for IPA in HT recipients include isolation of A. fumigatus in respiratory tract cultures prior to HT, reoperation, CMV disease, post-transplant hemodialysis, and cases of IPA in the institution in the two months before transplantation.7 In a study by Muñoz et al.,4 IPA-related mortality was 11/17 (65%), and total mortality was 17/27 (63%), but this cohort presented a high proportion of risk factors for IPA: hemodialysis in 19%, bacterial infection in 63%, and rejection episode in 44%. Also in this cohort, 82% of patients received either OKT3 or anti-thymocyte globulin as induction therapy. It is known that the stronger the immunosuppression, the higher the risk of infection. None of our patients needed hemodialysis, nor were there any rejection episodes requiring an increase in immunosuppression. Likewise, our patients received basiliximab instead of OKT3 or anti-thymocyte globulin. Baxiliximab is associated with fewer infections overall than OKT3 or anti-thymocyte globulin in solid organ transplantation.9

Although this case series could have suffered from publication bias, we consider our results to be due to early diagnosis based on serum galactomannan level and prompt bronchoscopy followed by initiation of aggressive treatment, as well as the patients’ clinical characteristics. Our findings can be summarized as improved outcomes resulting from early diagnosis, which has also been shown in patients with blood cancer and invasive fungal infections.

Finally, it appears that, as in many other fields of medicine, patients’ prognosis is improving as we learn more about complications and as new diagnostic techniques lead to earlier initiation of modern therapeutic strategies. As Montoya et al.3 concluded, patients suffering IPA in recent years may have a better prognosis than those treated before. Have we reached the point when mortality from IPA is decreasing?

ConclusionIPA is a potentially lethal complication after HT. Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of aggressive treatment are the cornerstone of better survival.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.