Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has significant benefits in selected patients, but its impact on the incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias remains the subject of debate. We analyzed the occurrence of appropriate therapies in patients undergoing CRT combined with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

MethodsWe studied 123 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <35%, who underwent successful implantation of CRT-ICD or ICD alone (primary prevention).

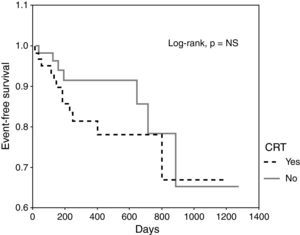

ResultsMean age was 63±12 years, LVEF 25±6%, and median follow-up 372 days. CRT-ICD devices were implanted in 63 patients (group A) and ICD alone in 60 (group B). In Group A 86% were clinical responders, with a lower prevalence of ischemic cardiomyopathy (30% vs. 72%), and more patients in NYHA class III before device implantation (90% vs. 7%) compared to those with ICD alone. There were no differences in the incidence of appropriate therapies (19% vs. 12%) or in the time to first therapy (305 days vs. 293 days). Overall mortality was 11% in group A and 12% in group B. Kaplan-Meier curves for arrhythmic events in patients with CRT showed no significant differences (HR 1.71, 95% CI 0.67-4.36, p=NS) compared to those without CRT.

ConclusionsDespite a higher rate of responders in patients with CRT-ICD for primary prevention, the incidence of appropriate therapies was similar to those with an ICD alone.

A terapêutica de ressincronização cardíaca (TRC) tem benefícios significativos em doentes seleccionados. O impacto desta modalidade na incidência de taquidisritmias ventriculares permanece controverso. Analisámos a ocorrência de terapêuticas apropriadas em doentes submetidos a TRC combinada com cardioversor-desfibrilhador (CDI).

MétodosEstudo de 123 doentes com fracção de ejecção ventricular esquerda (FEVE) <35%, submetidos a implantação com sucesso de TRC-CDI ou CDI isoladamente (prevenção primária).

ResultadosIdade média foi 63±12 anos, FEVE de 25±6%, seguimento mediano de 372 dias. Implantou-se TRC-CDI em 63 doentes (grupo A) e CDI isoladamente em 60 doentes (grupo B). No grupo A tivemos 86% de respondedores clínicos, menor prevalência de cardiomiopatia isquémica (30% versus 72%), e mais doentes em classe III da NYHA antes da implantação do dispositivo (90% versus 7%) comparativamente com o grupo com CDI isoladamente. Não se identificaram diferenças relativamente à incidência de terapêuticas apropriadas (19% versus 12%) ou no tempo para a primeira terapêutica (305 dias versus 293 dias). A mortalidade total foi de 11% no grupo A e de 12% no grupo B. As curvas de Kaplan-Meier para eventos arrítmicos em doentes com TRC, não mostraram diferenças significativas (HR 3,02, IC 95% 0,82 – 11,09, p=NS) comparativamente com doentes sem TRC.

ConclusõesEm doente submetidos a TRC-CDI por prevenção primária, apesar da elevada taxa de respondedores, a incidência de terapêuticas apropriadas não foi diferente do obtido em doentes com CDI isoladamente.

The benefits of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) for prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD) have been demonstrated in various clinical trials.1–4 The prevalence of heart failure (HF) ranges between 5 and 10% in Europe, with high long-term mortality due to worsening left ventricular (LV) function, as well as SCD.5 ICDs have been shown to be effective in terminating malignant ventricular arrhythmias and preventing SCD in patients with impaired LV function, improving the survival of high-risk patients but not their quality of life or HF symptoms.3,4 Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) can improve hemodynamic parameters and HF symptoms, reduce hospitalizations for decompensated HF, promote LV reverse remodeling and decrease mortality.6,7 It is, however, less clear whether CRT has an impact on the prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias. Although in theory LV reverse remodeling after CRT may help reduce their incidence, the rate of SCD remains high in patients treated by CRT alone. In the first report from the Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) study, CRT did not reduce the rate of SCD in the first 29 months of follow-up (CRT: 35% vs. medical therapy alone: 32%),7,8 while in the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillator in Heart Failure (COMPANION) trial, CRT with defibrillator back-up (CRT-ICD) led to lower overall mortality and SCD, which suggests that ventricular arrhythmias may be the cause of death in some patients undergoing CRT.9

Many patients who receive CRT are also candidates for an ICD, and it is therefore common to implant a combined CRT-ICD device. The present study aimed to analyze the clinical outcomes and incidence of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation (VT/VF) in HF patients treated with CRT-ICD.

MethodsWe retrospectively studied 123 consecutive patients, with no previously documented VT/VF, who underwent implantation of CRT-ICD or ICD alone in our institution. All patients met Class I criteria according to the AHA/ACC/NASPE/ESC guidelines at the time of implantation. Only patients with LV ejection fraction (LVEF) <35% and indication for primary prevention were included. Sixty patients with ICD alone were compared with 63 with CRT-ICD. All gave their informed consent for implantation of an ICD or CRT-ICD. Prescription of beta-blockers and amiodarone was based on the clinical judgement of the attending physician. Non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy was diagnosed after exclusion of significant stenosis of one or more coronary arteries.

The patients were routinely followed in the ICD clinic every 3-4 months, or earlier in cases of spontaneous ICD therapy or syncope, to interrogate the device and download the stored electrograms. Follow-up was at least 6 months in all patients. The incidence of appropriate therapies was assessed by two experienced electrophysiologists on the basis of the stored electrograms. Appropriate therapies were defined as antitachycardia pacing (ATP) or shocks due to sustained VT/VF. All data were entered in a database from the time of implantation. Patients with CRT-ICD were considered clinical responders if they presented sustained improvement of at least one NYHA functional class. Reverse remodeling in the CRT-ICD group was defined as improvement in LVEF of at least 25% compared to baseline.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Categorical variables are presented as percentages and were compared by the chi-square test with correction for continuity. Continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviation if they had a normal distribution and as medians and interquartile range otherwise (as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test), and were compared using the Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. The cumulative probability of freedom from appropriate ICD therapy was calculated by comparing Kaplan-Meier curves with the log rank test, assessed from the time of implantation. Cox regression analysis was also used to identify predictors of appropriate ICD therapy. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsWe studied 123 patients, mean age 63±12 years, 79% male, who underwent successful implantation of CRT-ICD or ICD alone. No patient was lost to follow-up, which was 456±329 days (median 372 days). Of this population, 15% received appropriate ICD therapies and overall mortality was 11%. Patient characteristics according to the type of device implanted are shown in Table 1. CRT-ICD devices were implanted in 51%, of whom 86% were considered clinical responders and 75% had documented reverse remodeling; there were no cases of reverse remodeling in the ICD group. There were also significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the two groups, including a higher prevalence of male gender and of ischemic cardiomyopathy in the group with ICD alone, and more patients in NYHA functional class >II in the CRT-ICD group. Baseline LVEF, length of follow-up, and prescription of beta-blockers and amiodarone were similar in the two groups.

Patient baseline characteristics and outcomes.

| CRT n=63 | ICD n=60 | p | |

| Age (years) | 62±11 | 63±13 | NS |

| Male (%) | 68 | 90 | 0.003 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy (%) | 30 | 72 | <0.001 |

| NYHA >II (%) | 94 | 7 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 24±6 | 26±5 | NS |

| Beta-blockers (%) | 87 | 78 | NS |

| Amiodarone (%) | 16 | 15 | NS |

| Follow-up (days) | 405 (192-655) | 315 (164-778) | NS |

| Mortality (%) | 11 | 12 | NS |

| Appropriate therapies at 6 months (%) | 13 | 5 | NS |

| Appropriate therapies at one year (%) | 16 | 7 | NS |

| Appropriate therapies during follow-up (%) | 19 | 12 | NS |

| ATP (%) | 13 | 12 | NS |

| Shocks (%) | 10 | 7 | NS |

| Detection of VA (%) | 35 | 40 | NS |

| Time to first ATP (days) | 332 (172-515) | 293 (143-640) | NS |

| Time to first shock (days) | 372 (165-372) | 293 (154-655) | NS |

| Time to first appropriate therapy (days) | 305 (164-305) | 293 (143-293) | NS |

ATP: antitachycardia pacing; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; VA: ventricular arrhythmia.

The cumulative incidence of appropriate ICD therapies for ventricular arrhythmias was similar in the two groups (Figure 1). None of the baseline variables was a predictor of appropriate therapy during follow-up, including CRT, even after adjustment for other variables (Table 2), nor did reverse remodeling reduce the incidence of appropriate therapies. CRT was not a predictor of ATP (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.38-2.93, p=NS) or shocks (HR 1.36, 95% CI 0.39-4.83, p=NS). The time to the first appropriate therapy was similar in the two groups (Table 1).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of appropriate therapies during follow-up in the total study population.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.96-1.03 | 0.625 | 0.99 | 0.95-1.03 | 0.578 |

| Male | 0.45 | 0.10-1.94 | 0.281 | 2.29 | 0.49-10.70 | 0.293 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1.28 | 0.52-3.15 | 0.597 | 1.80 | 0.61-5.30 | 0.289 |

| LVEF | 0.95 | 0.88-1.02 | 0.170 | 0.96 | 0.89-1.04 | 0.354 |

| Beta-blockers | 1.60 | 0.37-6.96 | 0.528 | 1.14 | 0.24-5.40 | 0.870 |

| Amiodarone | 1.06 | 0.34-3.30 | 0.919 | 1.33 | 0.40-4.39 | 0.644 |

| Reverse remodeling | 1.17 | 0.47-2.92 | 0.739 | 0.72 | 0.20-2.60 | 0.620 |

| CRT | 1.71 | 0.67-4.36 | 0.261 | 3.02 | 0.82-11.09 | 0.095 |

CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

ICDs have brought substantial benefits in reducing SCD, in both primary and secondary prevention.1–4 The Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implant Trial (MADIT)-II reported a 31% reduction in overall mortality in patients with myocardial infarction and LVEF ≤30%, even in those without documented nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, a benefit that was directly related to QRS duration.10 These findings were confirmed by the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT), which showed a 23% reduction in overall mortality with the use of ICDs.11 Combining CRT with ICD in selected patients can improve symptoms and quality of life and reduce complications and mortality.6,7 The COMPANION trial confirmed the superiority of CRT-ICD over ICD alone with optimized medical therapy in patients with heart failure and LVEF <35%, suggesting that SCD is an important cause of mortality in HF patients undergoing CRT.9 However, it is not clear whether CRT has an impact on the prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias. The first results from the CARE-HF study (after 29 months of follow-up) and a meta-analysis of CRT found no benefit in terms of reducing SCD.7,8There are various reports in the literature of an increased incidence of ventricular arrhythmias following CRT implantation. Shukla et al. reported VT/VF in 3.5% of patients early after CRT implantation, resolved by discontinuation of LV pacing.12 Medina-Ravell et al. found a marked increase in R-on-T ventricular extrasystoles in 14% of patients after CRT, which were completely inhibited by right ventricular endocardial pacing (one patient developed recurrent nonsustained polymorphic VT and another suffered incessant torsade de pointes).13 Rivero-Ayerza et al. reported a case of polymorphic VT induced by LV pacing.14 Other authors have demonstrated a significant reduction in the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias in patients upgraded to CRT-ICD (from 0.92±2.2 to 0.12±0.2 per month), and a lower frequency of ATP therapies with biventricular compared to no pacing (16% vs. 34%, p=0.04).15–17

It is plausible that the reverse remodeling observed after prolonged CRT would reduce wall stress and thus result in fewer ventricular arrhythmias.16 The evidence suggests that the myocardium is electrically and mechanically heterogeneous. Reversal of the transmural direction of activation following pericardial pacing (the result of the epicardium depolarizing and repolarizing earlier and the M cells later), as occurs in CRT, has been shown to increase the T(peak)-T(end) interval, a measure of transmural dispersion of repolarization, which is associated with spontaneous development of VT and increased inducibility.18,19 After CRT, some patients exhibit increased QT dispersion, a risk marker for major arrhythmic events, which suggests that there is a differential treatment effect and that CRT may be proarrhythmic in some patients.18 These findings have raised serious concerns about the proarrhythmic potential of CRT. Besides the changes in transmural dispersion of repolarization and despite reduced LV end-diastolic dimensions following CRT, electrical activation does not recover (electrical remodeling does not differ between patients with left bundle branch block under CRT and controls without CRT indication).20

In a prospective study of patients with an ICD incorporating CRT (44% with indication for primary prophylaxis) and a median follow-up of 556 days, the actuarial rate free of events (appropriate therapies) at one year was higher in primary than in secondary prevention (79% vs. 45.6%).21 In a multivariate model, the only independent predictor of appropriate therapies was indication for secondary prevention;21 the underlying disease (ischemic vs. non-ischemic) and functional class had no impact after multivariate analysis. Another study of HF patients treated with CRT-ICD for both primary and secondary prevention, with similar age, LVEF and percentage of individuals with ischemic etiology to the present study, found that a significant number of patients received appropriate ICD therapies – 20% in the first six months following CRT implantation.22 This study also found that improved functional class was associated with a significant reduction in the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias. In our study, 13% and 16% of patients in the CRT-ICD group had received appropriate therapies for episodes of VT/VF at six-month and one-year follow-up, respectively, lower percentages than those reported in the above-mentioned studies. However, only patients with indication for primary prevention were included in the present study and the rate of appropriate therapies was similar to that of the COMPANION trial, which also included only primary prevention patients and had a similar follow-up.23

A Mayo Clinic study of patients upgraded from ICD to CRT-ICD showed that the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate therapies did not change significantly, suggesting that CRT had no effect on the incidence of appropriate device therapy, even though 63% of the patients were in atrial fibrillation.24 Our results also showed no difference in the incidence of appropriate therapies between patients with CRT-ICD and those with ICD alone. During follow-up, the presence of a CRT device did not lead to a greater incidence of appropriate therapies or early events compared to ICD alone, which as mentioned above would be a cause for concern. Ischemic cardiopathy, one of the main factors distinguishing the two groups under analysis, was also not a predictor of appropriate therapies, as suggested in a previous study.21 Furthermore, reverse remodeling does not appear to have a protective effect against the occurrence of appropriate ICD therapies, even after adjustment for other variables, confirming the preliminary results we obtained in an echocardiographic study on the same subject, albeit on a small population sample.25 Thus, despite CRT's functional and structural benefits, it does not reduce the incidence of VT/VF in the first year following implantation. Candidates for CRT would therefore appear to benefit from a combined device for primary prevention of SCD. Another important point is that none of the other variables analyzed, including use of beta-blockers and amiodarone, predicted the occurrence of appropriate therapies, which highlights the need to find a test capable of predicting the risk of arrhythmias in these patients in order to facilitate clinical decisions.

LimitationsThe retrospective and observational nature of the study is its main limitation. The population was also heterogeneous, since it included patients with dilated cardiomyopathy of both ischemic and non-ischemic etiology. However, we attempted to minimize these population differences by the use of multivariate analysis to control for the effect of each variable studied. A further limitation is the relatively small sample size, albeit larger than those of the studies referred to in the discussion.

Factors that can trigger arrhythmias, such as ischemia, hypokalemia and hyperthyroidism, were not systematically recorded in the database. However, most patients were being closely monitored and it is unlikely that they developed significant exogenous arrhythmogenic factors during follow-up.

The CARE-HF study found a 36% reduction in overall mortality in patients with a CRT device during a 29-month follow-up.7 When this was extended to 36 months, the risk of death due to both HF and SCD was reduced.26 Thus, a longer follow-up was necessary to demonstrate a reduction in SCD. In the COMPANION trial, SCD accounted for 28% of all deaths in the group under optimized medical therapy, 37% in the group with CRT, and 17% in the group with CRT-ICD.23 These figures suggest that in advanced HF, the improvement seen with CRT is an appropriate therapeutic goal in the prevention of SCD in many but not all patients. However, there appears to be no direct benefit of CRT in terms of arrhythmic substrate early after CRT implantation. The mean follow-up in our study was 15 months, and a longer follow-up may have produced more beneficial results.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Timóteo, AT. Incidência de arritmias ventriculares em doentes com disfunção sistólica ventricular esquerda grave: existe benefício após terapêutica de ressincronização cardíaca? Rev Port Cardiol. 2011;30(11):823–828.