Pediatric hypertension has increased in the last decade, and it is thus crucial to identify the factors associated with the development of high blood pressure (BP) and other cardiovascular disorders. The aim of this study was to determine whether there is an association between high BP and sociodemographic and biochemical factors in schoolchildren.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study included 1201 children and adolescents, between seven and 17 years old, of both sexes. The sociodemographic data analyzed were gender, age, school system and socioeconomic status. Among biochemical indicators, blood glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) were assessed. In the analysis of BP, schoolchildren were classified as normal, borderline or hypertensive. Associations were tested using Poisson regression through prevalence ratios (PR).

ResultsHigh BP was identified in 16.2% of the students. In females, the prevalence of high BP was 7% lower than in males (p=0.001), but was higher among adolescents (PR: 1.11, p<0.001) and schoolchildren in the state school system (PR: 1.05; p=0.013). Concerning biochemical indicators, BP change was associated with pre-diabetes (PR: 1.09; p=0.001) and borderline HDL-C (PR: 1.09; p=0.007).

ConclusionAmong the sociodemographic factors associated with high BP are male gender, adolescence and attending the state education system. This condition was also associated with pre-diabetes and borderline HDL-C.

A hipertensão arterial pediátrica tem aumentado na última década, o que torna fundamental a identificação dos fatores associados ao desenvolvimento de pressão arterial (PA) elevada e outras doenças cardiovasculares. O objetivo do estudo foi verificar se existe associação entre PA alterada com fatores sociodemográficos e bioquímicos em escolares.

MétodoO estudo transversal foi composto por 1201 crianças e adolescentes, de sete a 17 anos de ambos os sexos. Os dados sociodemográficos avaliados foram: sexo, idade, rede escolar e nível socioeconómico. Entre os indicadores bioquímicos, avaliou-se: glicose, triglicerídeos, colesterol total, colesterol HDL (HDL-c) e colesterol LDL (LDL-c). Para a análise da PA alterada foram considerados os escolares limítrofes ou hipertensos. A associação foi testada por meio da regressão de Poisson, através dos valores de razão de prevalência (RP).

ResultadosA PA alterada foi verificada em 16,2% dos escolares. No sexo feminino, houve prevalência 6% menor (p=0,001) de PA alterada; a alteração foi maior entre os adolescentes (RP: 1,11; p<0,001) e entre os escolares da rede de ensino estadual (RP: 1,05; p=0,013). Quanto aos indicadores bioquímicos, a alteração da PA associou-se com pré-diabetes (RP: 1,09; p=0,001) e com HDL-c limítrofe (RP: 1,09; p=0,007).

ConclusãoEntre os fatores sociodemográficos associados com PA alterada estão o sexo masculino, os adolescentes e os escolares da rede de ensino estadual. A alteração da PA associou-se, também, com escolares pré-diabéticos e com HDL-c limítrofe.

Hypertension is one of the main factors that lead to cardiovascular disease.1 This chronic illness is common among adolescents and is associated with disorders including high blood glucose2 and obesity/overweight.3 Studies on children and adolescents have shown that hypertension can be detected at this stage, and early diagnosis can help prevent the occurrence of future complications arising from high blood pressure (BP) and other cardiovascular problems that may develop if the condition is not diagnosed until later in life.4,5

The incidence of pediatric hypertension has increased in the last decade,6 which makes it essential to identify the factors – particularly sociodemographic and economic, but also biochemical – associated with the development of high BP and other cardiovascular disorders in children and adolescents.7 Clustering of risk factors, including high total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, body fat and blood glucose, is strongly associated with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease in this population.8

In this context, there is a clear need for increased awareness of pediatric hypertension as a public health issue, in order to enable early prevention and diagnosis of this condition, and thereby to mitigate its harmful effects.9 In light of this, this study aims to determine whether there is an association between high BP and sociodemographic and biochemical factors in children.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study included 1201 children and adolescents, from seven to 17 years old, of both sexes, attending 18 schools in the municipality of Santa Cruz do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul state, in the municipal, state and private school systems. The study is part of a broader research program at the University of Santa Cruz do Sul (UNISC), ‘Schoolchildren's Health – Stage III’, approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of UNISC under protocol number 714.216/2014. Only children whose parents or guardians provided their written informed consent and who provided their own written consent were included in the study.

The population was selected by cluster sampling, in accordance with the population density of each region of the municipality (center, north, south, east and west), in both urban and rural areas. The sample calculation was performed using G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Dusseldorf, Germany). Poisson regression was used as the statistical test (presence vs. absence of high BP as a dependent variable). The recommendations of Faul et al.10 were followed to obtain the calculation parameters of test power (1-β) = 0.95, effect size 0.30 and level of significance α=0.05, arriving at a minimum sample of 655 schoolchildren to make up the study population. Ten children were excluded from the study as they had cardiac disease.

Sociodemographic data (gender, age, school and socio-economic status) were self-reported by the schoolchildren. The study subjects were subsequently categorized by age as children (up to nine years old) or adolescents (10 years old or over), following the classification proposed by the World Health Organization.11 Socioeconomic status was assessed using the criteria of the Brazilian Association of Research Companies (ABEP),12 which divide individuals into five categories: A, B, C, D and E. Categories A and B (grouped together) indicate the highest socioeconomic status, category C intermediate socioeconomic status, and categories D and E (also grouped together) low socioeconomic status.

BP was assessed with the child seated and at rest. A sphygmomanometer and stethoscope were used on the right arm. Cuffs of different sizes were used depending on arm circumference. Systolic (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were classified in accordance with the VI Brazilian Guidelines on Hypertension, which define normal BP as below the 90th percentile for gender, age and height.13 Children with high SBP and/or DBP (90th percentile or above) were defined as borderline or hypertensive.

Blood was collected by qualified technicians for analysis of biochemical data after a 12-hour fasting period. The blood was transferred to tubes containing clot activator, then placed in a water bath and centrifuged to separate the serum. Biochemical parameters (glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol and HDL-C) were measured in an automated analyzer (Miura One, ISE, Rome, Italy). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the formula established by Friedewald et al.14

The sample data were analyzed through descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage). The association between high BP and sociodemographic and biochemical indicators was tested using Poisson regression, through prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Values of p<0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 23.0 software (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

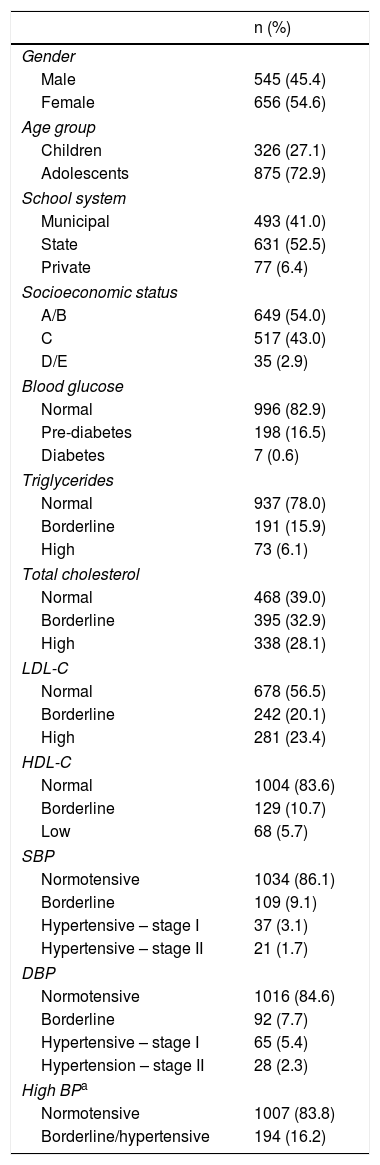

ResultsThe characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that 54% of the sample were female and adolescents were the largest age group (72.9%). Regarding biochemical profiles, a large number of children had borderline or high total cholesterol (61.0%), LDL-C (43.5%) and triglycerides (22%), and borderline or low HDL-C (16.4%). Abnormal blood glucose levels were observed in 17.1% of the children and borderline or high BP in 16.2%.

Characteristics of the study population (n=1201).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 545 (45.4) |

| Female | 656 (54.6) |

| Age group | |

| Children | 326 (27.1) |

| Adolescents | 875 (72.9) |

| School system | |

| Municipal | 493 (41.0) |

| State | 631 (52.5) |

| Private | 77 (6.4) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| A/B | 649 (54.0) |

| C | 517 (43.0) |

| D/E | 35 (2.9) |

| Blood glucose | |

| Normal | 996 (82.9) |

| Pre-diabetes | 198 (16.5) |

| Diabetes | 7 (0.6) |

| Triglycerides | |

| Normal | 937 (78.0) |

| Borderline | 191 (15.9) |

| High | 73 (6.1) |

| Total cholesterol | |

| Normal | 468 (39.0) |

| Borderline | 395 (32.9) |

| High | 338 (28.1) |

| LDL-C | |

| Normal | 678 (56.5) |

| Borderline | 242 (20.1) |

| High | 281 (23.4) |

| HDL-C | |

| Normal | 1004 (83.6) |

| Borderline | 129 (10.7) |

| Low | 68 (5.7) |

| SBP | |

| Normotensive | 1034 (86.1) |

| Borderline | 109 (9.1) |

| Hypertensive – stage I | 37 (3.1) |

| Hypertensive – stage II | 21 (1.7) |

| DBP | |

| Normotensive | 1016 (84.6) |

| Borderline | 92 (7.7) |

| Hypertensive – stage I | 65 (5.4) |

| Hypertension – stage II | 28 (2.3) |

| High BPa | |

| Normotensive | 1007 (83.8) |

| Borderline/hypertensive | 194 (16.2) |

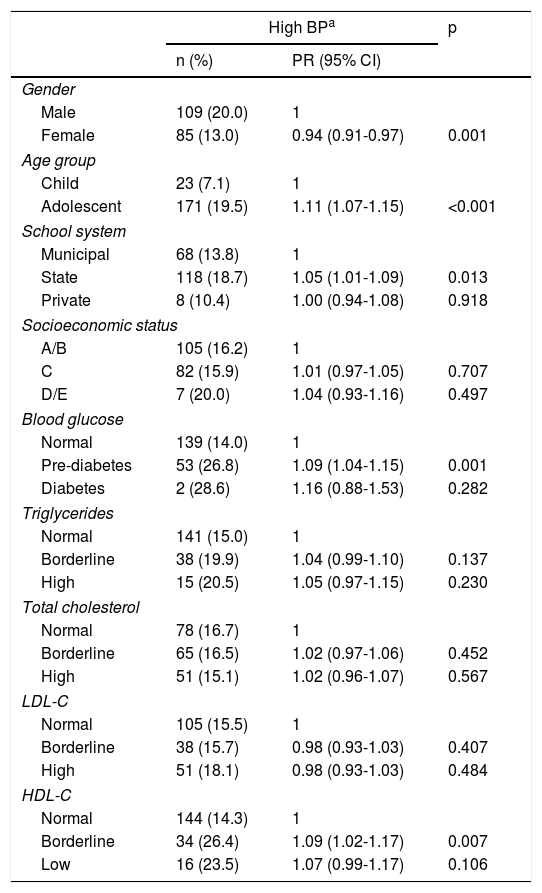

Table 2 reveals that there were fewer cases of high BP (PR 0.94; p=0.001) among females than among males. More cases of high BP were noted among adolescents (PR 1.11; p<0.001) and among schoolchildren in the state school system (PR 1.05; p=0.013). Regarding biochemical indicators, high BP was associated with pre-diabetes (PR 1.09; p=0.001) and with borderline HDL-C (PR 1.09; p=0.007).

Relationship between sociodemographic and biochemical factors and high blood pressure.

| High BPa | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | PR (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 109 (20.0) | 1 | |

| Female | 85 (13.0) | 0.94 (0.91-0.97) | 0.001 |

| Age group | |||

| Child | 23 (7.1) | 1 | |

| Adolescent | 171 (19.5) | 1.11 (1.07-1.15) | <0.001 |

| School system | |||

| Municipal | 68 (13.8) | 1 | |

| State | 118 (18.7) | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | 0.013 |

| Private | 8 (10.4) | 1.00 (0.94-1.08) | 0.918 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| A/B | 105 (16.2) | 1 | |

| C | 82 (15.9) | 1.01 (0.97-1.05) | 0.707 |

| D/E | 7 (20.0) | 1.04 (0.93-1.16) | 0.497 |

| Blood glucose | |||

| Normal | 139 (14.0) | 1 | |

| Pre-diabetes | 53 (26.8) | 1.09 (1.04-1.15) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 2 (28.6) | 1.16 (0.88-1.53) | 0.282 |

| Triglycerides | |||

| Normal | 141 (15.0) | 1 | |

| Borderline | 38 (19.9) | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | 0.137 |

| High | 15 (20.5) | 1.05 (0.97-1.15) | 0.230 |

| Total cholesterol | |||

| Normal | 78 (16.7) | 1 | |

| Borderline | 65 (16.5) | 1.02 (0.97-1.06) | 0.452 |

| High | 51 (15.1) | 1.02 (0.96-1.07) | 0.567 |

| LDL-C | |||

| Normal | 105 (15.5) | 1 | |

| Borderline | 38 (15.7) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.407 |

| High | 51 (18.1) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.484 |

| HDL-C | |||

| Normal | 144 (14.3) | 1 | |

| Borderline | 34 (26.4) | 1.09 (1.02-1.17) | 0.007 |

| Low | 16 (23.5) | 1.07 (0.99-1.17) | 0.106 |

Poisson regression analysis of normotensive vs. borderline or hypertensive.

In this study, 16.2% of the schoolchildren presented high BP, with higher prevalences among adolescents. It is important to detect high BP in childhood and adolescence, given that children with high BP from six years of age are more likely to present hypertension and accelerated remodeling of the cardiovascular system in adulthood.15

Other studies in Brazil have detected BP levels close to those of our study. A study of adolescents aged 14-19 years from the South region of the country observed a prevalence of high BP of 12.4%.16 A nationwide study observed a prevalence of hypertension of 12.5% in schoolchildren from the same region. The same survey also detected a greater prevalence of hypertension in males and among older children, corroborating the results of our study, which was also performed in the south of the country.17 Moura et al.,2 in a study of 211 schoolchildren aged 12-18 years in the Northeast region of the country, found hypertension in 13.7% of adolescents in their study. Meanwhile, in the Southeast region, a study of 854 adolescents aged between 17 and 19 years showed a 19.4% prevalence of hypertension in the sample.18

In a systematic review of studies published between 2004 and 2014, the prevalence of hypertension ranged from 2.3% to 13.8%, depending on nutritional status and methodology used, and the prevalence of pre-hypertension was 3.8-40.6%, in a sample of schoolchildren aged from six to 10 years old attending public and private schools in different municipalities in Brazil.19 Unlike in our study, lower rates of hypertension were observed in a study on schoolchildren aged from six to 13 years in Vila Velha, Espírito Santo state, in which 7.3% of the children had high BP.20 However, the rate was higher in Quadros et al.’s study21 of 1139 schoolchildren aged from six to 18 years in the municipality of Amargosa, Bahia state, in which 35.2% of adolescents and 9.4% of children had high BP, and, also as in our study, they found an association of high BP with age group.

Higher levels of BP have been observed in other countries. In Portuguese children and adolescents (n=5381), hypertension was identified in 12.8% of the sample; in addition, the prevalence of normal-high BP was 21.6%. The data were similar in both boys and girls.22 However, these figures were lower in a previous study on children and adolescents in the Central region of Portugal (n=1618), in which the prevalence of hypertension was 9.8%, higher among girls (15.0% vs. 9.1%; p<0.05). High-normal BP was found in 18.2%.23

A study carried out in Lithuania of 7457 adolescents aged between 12 and 15 years recorded prevalences of 12.8% and 22.2% of pre-hypertension and hypertension, respectively.24 Similarly, Yang et al.25 found higher values in a study of 2363 Korean children and adolescents aged between 10 and 18 years, of whom 19.2% had hypertension.

A study by May et al.26 carried out in the USA on a sample of 3383 adolescents aged between 12 to 19 years found a prevalence of 14% with pre-hypertension/hypertension, which was also higher among older schoolchildren, corroborating our study. On the other hand, Kelishadi et al.27 observed lower values than in our study; they detected high BP in 3.7% of a sample of 13486 schoolchildren from 30 provinces of Iran aged between six to 18 years, with a higher rate observed in males.

In our study, fewer females had high BP than males, as has also been observed in other studies. A cross-sectional study carried out in 2005 in Tunisia, based on a sample of 2870 individuals aged between 15 and 19 years, observed more frequent high BP among boys (46.1%) than among girls (33.3%).28 Another cross-sectional study, analyzing 145 individuals from 12 to 18 years old in the city of Picos, Piauí state, Brazil, also observed a greater rate of high BP among males than in females (59.3% and 48.4%, respectively).29 Similar findings were observed in the study by Silva et al.,16 in which the greatest prevalence of high BP was observed in males.

Musil et al.30 also identified a greater prevalence of high BP in boys (36.8%) than in girls (28.5%) in a study of 965 schoolchildren, in whom a family history of hypertension was the most common risk factor among children with high BP. A higher prevalence in boys was also observed by Ejike et al.,31 in a study of 843 adolescents in the state of Kogi, Nigeria. By contrast, Bozza et al.32 noted no difference between the sexes in the prevalence of high BP in a sample of 1242 students at public schools in the city of Curitiba, Paraná state, Brazil. The same study also revealed that 34.1% of the sample had never had their BP measured, which demonstrates the need for more studies to assess this variable in study populations.

Regarding the different school systems, our study demonstrated that high BP was more prevalent in schools in the municipal system, unlike in other studies on Brazilian schoolchildren. Quadros et al.21 reported a higher percentage of children and adolescents with high BP in the private system (31.9%) than in the public system (26.6%). Similarly, Costanzi et al.33 observed that there were almost twice as many (24.7%) children with high BP in private schools as in state schools (13.5%) and municipal schools (11.3%). Also, students from private schools were significantly more likely to have high BP than students attending public schools in a study by Rosaneli et al.34

Regarding the biochemical parameters analyzed in our study, an association was observed between high BP and pre-diabetes and borderline HDL-C. A study by Flynn35 corroborates this finding, indicating that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia (pre-diabetes or diabetes) can contribute to the development of vascular lesions by potentiating the atherosclerotic process and cardiovascular events. Mardones et al.36 also found that high BP was associated with insulin resistance, a characteristic of pre-diabetes and diabetes, in Chilean children and adolescents.

In a cross-sectional study of 211 adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years, Moura et al.2 found that adolescents with high blood glucose had a greater probability of developing systemic hypertension. Similarly, adolescents with pre-diabetes had higher SBP than those with normal blood glucose levels.37

Furthermore, Dost et al.,38 in 3529 children with type 1 diabetes, found that BP was higher in this group than in healthy controls, and also that BP was higher in females and increased with age. Similarly, Bradley et al.39 observed that adolescents with type 1 diabetes had early changes in BP, which demonstrates the importance of research to clarify this relationship, in order to enable identification of individuals with a higher risk of cardiovascular disorders.

Regarding the relationship between BP and HDL-C, in a study by Dalili et al.40 in 1005 adolescents, low HDL-C was among the factors most strongly correlated with high BP. Similarly, in a study of 1309 children and adolescents aged from five to 17 years, Cárdenas-Cárdenas et al.41 observed that SBP and DBP levels increased and HDL-C levels fell as body fat increased.

In a study by Soubeiga et al.42 of adults aged between 25 and 64 years, a population different from that of our study, low HDL-C levels were also significantly associated with an increased risk of high BP, while Sousa et al.43 observed that 6.2% of the adult subjects assessed presented low plasma HDL-C levels and above-normal BP, although, unlike in our study, there was no association between the two variables.

The limitations and strengths of this study should be pointed out. Firstly, a strong point is the size of the sample, which distinguishes it from other studies carried out in Brazil and in other countries, as large study populations are necessary for wide-ranging research. However, the study has some limitations, including its cross-sectional nature, which prevents the establishment of cause-effect relationships. Also, the analysis did not consider factors such as diet, body composition and levels of exercise, which may have influenced the BP measurements.

ConclusionA significant percentage of schoolchildren with high BP was found. The associated sociodemographic factors include male gender, adolescence, and attending the state school system. High BP was associated with pre-diabetes and with borderline HDL-C. We suggest that identification of factors associated with the presence of high BP may be an important tool for developing public health strategies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the recipients of grants from the research agencies FAPERGS and CNPq for their help in carrying out the study, and also the schoolchildren and schools that participated in this study.

Please cite this article as: Reuter CP, Rodrigues ST, Barbian CD, et al. Pressão arterial elevada em escolares: fatores sociodemográficos e bioquímicos associados. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:195–201.