We describe the clinical characteristics, management and outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute heart failure in a south-west European cardiology department. We sought to identify the determinants of length of stay and heart failure rehospitalization or death during a 12-month follow-up period.

Methods and ResultsThis was a retrospective cohort study including all patients admitted during 2010 with a primary or secondary diagnosis of acute heart failure. Death and readmission were followed through 2011.

Of the 924 patients admitted, 201 (21%) had acute heart failure, 107 (53%) of whom had new-onset acute heart failure. The main precipitating factors were acute coronary syndrome (63%) and arrhythmia (14%). The most frequent clinical presentations were heart failure after acute coronary syndrome (63%), chronic decompensated heart failure (47%) and acute pulmonary edema (21%). On admission 73% had left ventricular ejection fraction <50%. Median length of stay was 11 days and in-hospital mortality was 5.5%. The rehospitalization rate was 21% and 24% at six and 12 months, respectively. All-cause mortality was 16% at 12 months. The independent predictors of rehospitalization or death were heart failure hospitalization during the previous year (Hazard ratio − HR − 3.177), serum sodium <135mmol/l on admission (HR 1.995) and atrial fibrillation (HR 1.791). Reduced left ventricular ejection fraction was associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization or death (HR 0.518).

ConclusionsOur patients more often presented new-onset acute heart failure, due to an acute coronary syndrome, with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Several predictive factors of death or rehospitalization were identified that may help to select high-risk patients to be followed in a heart failure management program after discharge.

Dada a escassa informação relativa aos internamentos por insuficiência cardíaca aguda em serviços de Cardiologia portugueses, procedemos à sua caracterização. Pretendemos identificar os determinantes de maior duração de internamento e de rehospitalização ou morte aos 12 meses.

Métodos e resultadosRealizámos um estudo de cohort retrospetivo, incluindo os doentes admitidos em 2010 com diagnóstico primário ou secundário de insuficiência cardíaca aguda. A ocorrência de morte ou rehospitalização foi acompanhada durante 2011.

Do total de 924 hospitalizações, 201 (21%) apresentavam insuficiência cardíaca aguda, sendo o primeiro episódio em 107 (53%) das mesmas. Os principais fatores precipitantes foram síndrome coronária aguda (63%) e arritmia (14%). As apresentações clínicas mais comuns foram insuficiência cardíaca no contexto de síndrome coronária aguda (63%), insuficiência cardíaca crónica descompensada (46%) e edema pulmonar agudo (21%). Na admissão, 73% tinham fração de ejeção ventricular esquerda < 0,50. A duração mediana de internamento foi 11 dias e a mortalidade intra-hospitalar foi 5,5%. A taxa de rehospitalização aos 6 e 12 meses foi 21% e 24%, respetivamente. A mortalidade por todas as causas, aos 12 meses, foi 16%. Os factores preditores de rehospitalização ou morte foram hospitalização por insuficiência cardíaca aguda no ano anterior (Hazard ratio – HR – 3,177), sódio sérico < 135 mEq/L na admissão (HR 1,995), fibrilhação auricular (HR 1,791). Fracção de ejecção ventricular esquerda deprimida na admissão associou-se a menor risco de rehospitalização ou morte (HR 0,518).

ConclusõesOs nossos doentes apresentavam mais frequentemente insuficiência cardíaca aguda de novo, com fração de ejeção ventricular esquerda deprimida, no contexto de síndrome coronária aguda. Os vários fatores preditores de mortalidade ou rehospitalização identificados poderão contribuir para selecionar os doentes de alto risco que justificam acompanhamento especializado numa clínica de insuficiência cardíaca.

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

acute coronary syndrome

atrial fibrillation

acute heart failure

angiotensin receptor blocker

beta-blocker

B-type natriuretic peptide

calcium channel blocker

chronic decompensated heart failure

coronary heart disease

chronic heart failure

confidence interval

diastolic blood pressure

electrocardiogram

European Society of Cardiology

heart failure

hazard ratio

intensive cardiac care unit

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

left atrial diameter

length of stay

left ventricular end-diastolic diameter

left ventricular ejection fraction

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

systolic blood pressure

standard deviation

ventricular tachyarrhythmia

Acute heart failure (AHF) is a major public health concern because of its increasing prevalence and associated high morbidity, mortality and costs.1–5 Despite being one of the most frequent reasons for hospitalization in western countries, it has received much less attention than chronic heart failure (CHF), and large-scale studies specifically addressing AHF are relatively scarce.6,7

AHF is associated with a high rate of rehospitalization but little is known regarding the most relevant predictive factors. It is therefore important to develop appropriate predictive models that might help to appropriately stratify AHF patients and improve their management and follow-up.8

Moreover, although several studies have been conducted in Europe and the USA on the clinical characteristics, treatment and outcome of AHF patients, little information is available on this subject in Portugal.9

In the present study we describe the clinical characteristics, hospital management and outcomes of AHF patients admitted to a Portuguese cardiology department, and present a predictive model for readmission or death at 12 months in this population.

ObjectivesThe primary objective of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics, hospital management and outcomes of patients hospitalized with AHF.

The secondary objectives were:

- •

to compare patients with AHF and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) as the precipitating factor vs. patients with AHF and no ACS;

- •

to compare drug prescriptions on admission and at discharge;

- •

to identify factors associated with longer hospital length of stay (LOS);

- •

to identify risk factors for heart failure (HF) rehospitalization or death.

This was a hospital-based observational retrospective cohort study, conducted at the Cardiology Department of Hospital de S. João, Porto, Portugal. Demographic, clinical and follow-up data were collected between February 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011, ensuring a minimum follow-up of one year for all patients.

Inclusion criteriaAll patients admitted to the cardiology department between January 1 and December 31, 2010 were screened. Paper-based and computerized clinical records on the 924 patients admitted during the study period were retrieved and analyzed by one investigator in order to find eligible patients who met one of the following inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteriaScheduled hospitalizations or hospitalizations in the context of cardiac surgery were considered exclusion criteria.

In order to avoid duplicate records, readmissions to the hospital during the study period were not counted as new cases.

Data collectionData on patient demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities and history of cardiac disease or HF, and results of ECG, hemodynamic, echocardiographic examinations and laboratory tests were collected, as well as on the etiology and the possible precipitating factors of AHF, drug prescriptions before and following admission, concomitant medication and the main diagnostic or therapeutic procedures performed during hospitalization. The hospital LOS of patients was also recorded; in cases of patients transferred to another hospital or to another ward, it was recorded at the time of transfer. Data regarding death or rehospitalization were obtained from the patient's electronic record and did not include admissions to another hospital or death not recorded in the hospital's administrative or clinical database. For all living patients, the follow-up period ended on December 31, 2011.

Data analysisCategorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, and quantitative variables as means and standard deviation (SD) or medians and 25th percentile–75th percentile (p25–p75) as appropriate, depending on the empirical distribution of the variables.

Subgroups of patients were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the t test and Mann–Whitney rank-sum test for symmetrical and asymmetrical quantitative variables, respectively. The normality of the distribution of quantitative variables was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Simple and multiple linear regression models were used to analyze the variable LOS, which was logarithmically transformed in order to normalize its initially asymmetrical distribution. Survival analysis was used to analyze determinants of rehospitalization or death. For graphs of survival probability, the crude effect of each variable was tested with the log-rank test and multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox regression model. In the final analysis, all variables were taken into account to obtain a fully adjusted model. For each variable the assumption of proportional hazards was tested.

In univariate and multivariate regression analysis, the dependent variables were LOS and an adverse event, defined as HF rehospitalization or death during the follow-up period. The independent variables were age, gender, ischemic etiology, type (new-onset vs. decompensated chronic HF), history of HF hospitalization in the previous 12 months, obesity, diabetes, intensive cardiac care unit (ICCU) admission, LOS and the following admission findings: systolic blood pressure <100mmHg, heart rate <70 bpm, serum sodium <135 mmol/l, serum potassium >4.3mmol/l, creatinine clearance <30ml/min, anemia (hemoglobin lower than 130g/l in men and 120g/dl in women), serum B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) >500 pg/ml, atrial fibrillation (AF), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%. In the independent variables, the variable etiology was included instead of ACS as precipitating factor, since there was a close association between the two variables but etiology was considered more informative.

All tests were two-sided and p values less than 0.05 were considered as indicating significant differences. The analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows statistical software.

EthicsThe study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital's ethics committee.

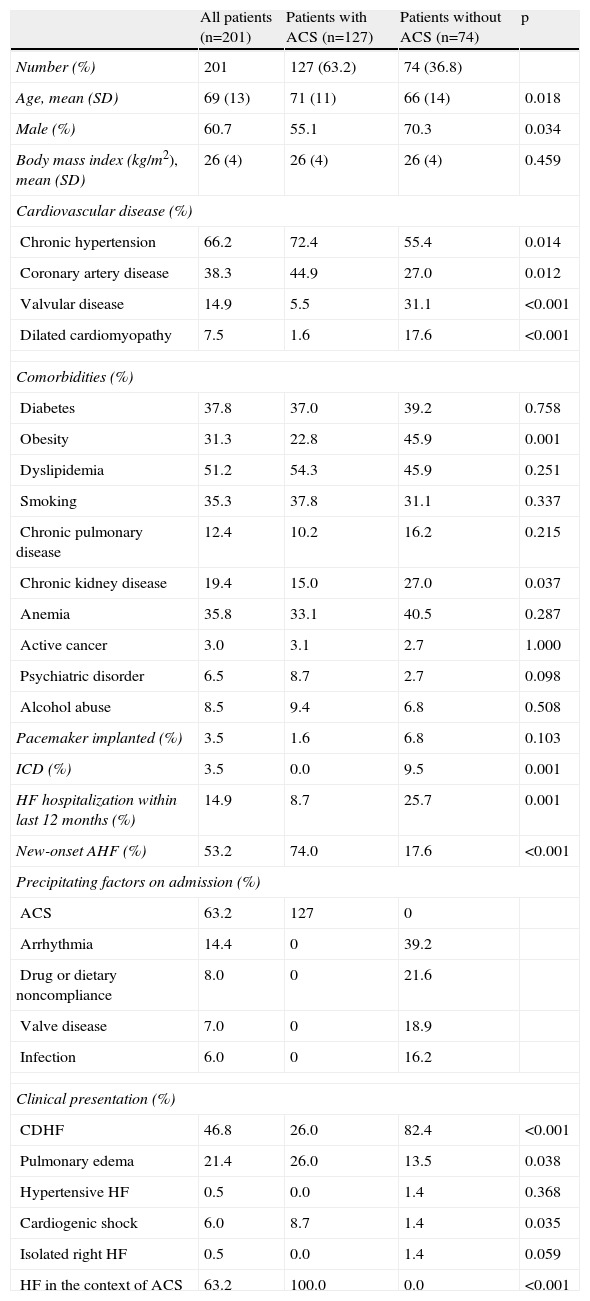

ResultsBaseline characteristicsOf a total of 924 patients admitted to the cardiology department over a period of one year, 201 (21%) presenting with AHF were enrolled. Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. New-onset AHF occurred in more than 50% of cases. Hypertension and coronary heart disease (CHD) were the most prevalent underlying diseases, but all the cardiovascular risk factors were relatively frequent. The most common precipitating factor was ACS (63.3% of patients), followed by arrhythmia (14.4% of patients). The most frequent clinical presentation by far was HF in the context of ACS, followed by chronic decompensated heart failure (CDHF) and pulmonary edema. Interestingly, pulmonary edema was approximately twice as common in patients presenting with ACS than in those with no ACS, while CDHF was approximately three times more frequent in those without ACS than in those with. The majority of patients had reduced LVEF on admission.

Underlying diseases, type of onset, precipitating factors and clinical presentation of acute heart failure patients.

| All patients (n=201) | Patients with ACS (n=127) | Patients without ACS (n=74) | p | |

| Number (%) | 201 | 127 (63.2) | 74 (36.8) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 69 (13) | 71 (11) | 66 (14) | 0.018 |

| Male (%) | 60.7 | 55.1 | 70.3 | 0.034 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26 (4) | 26 (4) | 26 (4) | 0.459 |

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | ||||

| Chronic hypertension | 66.2 | 72.4 | 55.4 | 0.014 |

| Coronary artery disease | 38.3 | 44.9 | 27.0 | 0.012 |

| Valvular disease | 14.9 | 5.5 | 31.1 | <0.001 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 7.5 | 1.6 | 17.6 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 37.8 | 37.0 | 39.2 | 0.758 |

| Obesity | 31.3 | 22.8 | 45.9 | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 51.2 | 54.3 | 45.9 | 0.251 |

| Smoking | 35.3 | 37.8 | 31.1 | 0.337 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 12.4 | 10.2 | 16.2 | 0.215 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 19.4 | 15.0 | 27.0 | 0.037 |

| Anemia | 35.8 | 33.1 | 40.5 | 0.287 |

| Active cancer | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 1.000 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 6.5 | 8.7 | 2.7 | 0.098 |

| Alcohol abuse | 8.5 | 9.4 | 6.8 | 0.508 |

| Pacemaker implanted (%) | 3.5 | 1.6 | 6.8 | 0.103 |

| ICD (%) | 3.5 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 0.001 |

| HF hospitalization within last 12 months (%) | 14.9 | 8.7 | 25.7 | 0.001 |

| New-onset AHF (%) | 53.2 | 74.0 | 17.6 | <0.001 |

| Precipitating factors on admission (%) | ||||

| ACS | 63.2 | 127 | 0 | |

| Arrhythmia | 14.4 | 0 | 39.2 | |

| Drug or dietary noncompliance | 8.0 | 0 | 21.6 | |

| Valve disease | 7.0 | 0 | 18.9 | |

| Infection | 6.0 | 0 | 16.2 | |

| Clinical presentation (%) | ||||

| CDHF | 46.8 | 26.0 | 82.4 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary edema | 21.4 | 26.0 | 13.5 | 0.038 |

| Hypertensive HF | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.368 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 6.0 | 8.7 | 1.4 | 0.035 |

| Isolated right HF | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.059 |

| HF in the context of ACS | 63.2 | 100.0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

p value for difference between patients presenting with or without ACS. Anemia defined as serum hemoglobin on admission <130g/l for men and 120g/l for women; all other comorbidities as reported. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AHF: acute heart failure; CDHF: chronic decompensated heart failure; HF: heart failure; ICD: implantable cardioverter/defibrillator; SD: standard deviation.

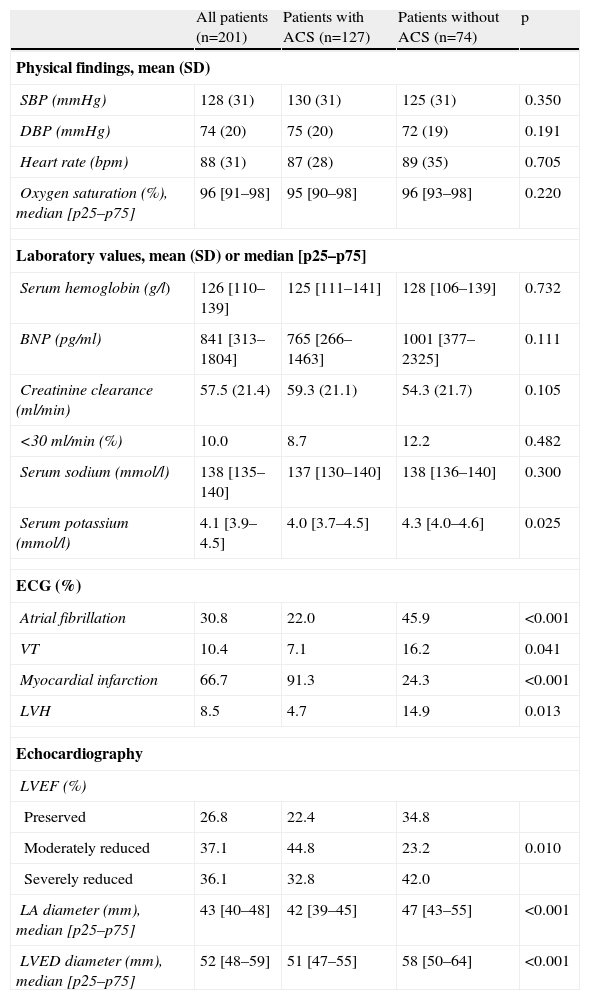

Physical, laboratory, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings on admission.

| All patients (n=201) | Patients with ACS (n=127) | Patients without ACS (n=74) | p | |

| Physical findings, mean (SD) | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 128 (31) | 130 (31) | 125 (31) | 0.350 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74 (20) | 75 (20) | 72 (19) | 0.191 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 88 (31) | 87 (28) | 89 (35) | 0.705 |

| Oxygen saturation (%), median [p25–p75] | 96 [91–98] | 95 [90–98] | 96 [93–98] | 0.220 |

| Laboratory values, mean (SD) or median [p25–p75] | ||||

| Serum hemoglobin (g/l) | 126 [110–139] | 125 [111–141] | 128 [106–139] | 0.732 |

| BNP (pg/ml) | 841 [313–1804] | 765 [266–1463] | 1001 [377–2325] | 0.111 |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/min) | 57.5 (21.4) | 59.3 (21.1) | 54.3 (21.7) | 0.105 |

| <30 ml/min (%) | 10.0 | 8.7 | 12.2 | 0.482 |

| Serum sodium (mmol/l) | 138 [135–140] | 137 [130–140] | 138 [136–140] | 0.300 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/l) | 4.1 [3.9–4.5] | 4.0 [3.7–4.5] | 4.3 [4.0–4.6] | 0.025 |

| ECG (%) | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 30.8 | 22.0 | 45.9 | <0.001 |

| VT | 10.4 | 7.1 | 16.2 | 0.041 |

| Myocardial infarction | 66.7 | 91.3 | 24.3 | <0.001 |

| LVH | 8.5 | 4.7 | 14.9 | 0.013 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF (%) | ||||

| Preserved | 26.8 | 22.4 | 34.8 | |

| Moderately reduced | 37.1 | 44.8 | 23.2 | 0.010 |

| Severely reduced | 36.1 | 32.8 | 42.0 | |

| LA diameter (mm), median [p25–p75] | 43 [40–48] | 42 [39–45] | 47 [43–55] | <0.001 |

| LVED diameter (mm), median [p25–p75] | 52 [48–59] | 51 [47–55] | 58 [50–64] | <0.001 |

p value for difference between patients presenting with or without ACS. DBP: diastolic blood pressure; LA: left atrial; LVED: left ventricular end-diastolic; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; SBP: systolic blood pressure; SD: standard deviation; VT: ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Patients presenting with ACS were significantly younger, more often women and less likely to have a history of HF; they more often had chronic hypertension and CHD. On the other hand, patients without ACS more frequently had valvular disease and dilated cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy pattern on the ECG, larger left atrial diameter and AF.

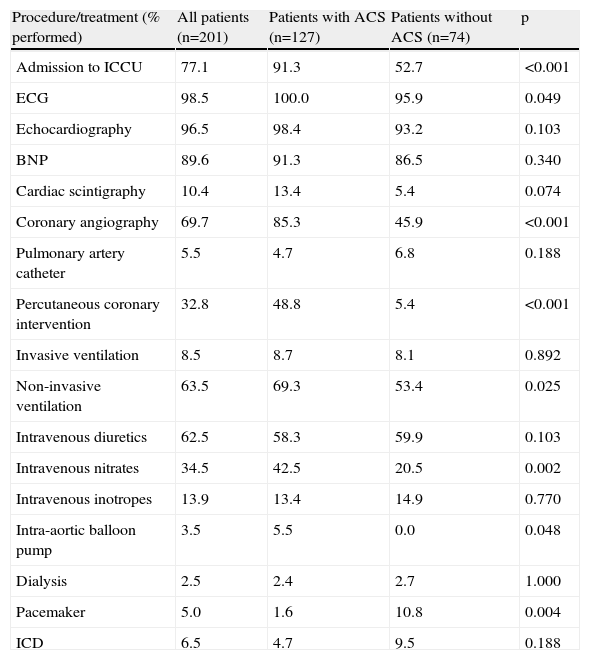

Hospital course and managementEchocardiographic examination and BNP measurement were performed in most patients and the majority were admitted to the ICCU and underwent coronary angiography. Overall use of in-hospital resources was similar in both ACS and non-ACS groups (Table 3), although a higher proportion of ACS patients were admitted to the ICCU. Non-invasive ventilation, intravenous nitrates and diuretics were the basis of therapy and the first two were more often used in ACS patients.

Diagnostic investigations, procedures and acute cardiac care.

| Procedure/treatment (% performed) | All patients (n=201) | Patients with ACS (n=127) | Patients without ACS (n=74) | p |

| Admission to ICCU | 77.1 | 91.3 | 52.7 | <0.001 |

| ECG | 98.5 | 100.0 | 95.9 | 0.049 |

| Echocardiography | 96.5 | 98.4 | 93.2 | 0.103 |

| BNP | 89.6 | 91.3 | 86.5 | 0.340 |

| Cardiac scintigraphy | 10.4 | 13.4 | 5.4 | 0.074 |

| Coronary angiography | 69.7 | 85.3 | 45.9 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary artery catheter | 5.5 | 4.7 | 6.8 | 0.188 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 32.8 | 48.8 | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| Invasive ventilation | 8.5 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 0.892 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 63.5 | 69.3 | 53.4 | 0.025 |

| Intravenous diuretics | 62.5 | 58.3 | 59.9 | 0.103 |

| Intravenous nitrates | 34.5 | 42.5 | 20.5 | 0.002 |

| Intravenous inotropes | 13.9 | 13.4 | 14.9 | 0.770 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 3.5 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.048 |

| Dialysis | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 1.000 |

| Pacemaker | 5.0 | 1.6 | 10.8 | 0.004 |

| ICD | 6.5 | 4.7 | 9.5 | 0.188 |

p value for difference between patients presenting with or without ACS. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; ICCU, intensive cardiac care unit; ICD, implantable cardioverter/defibrillator.

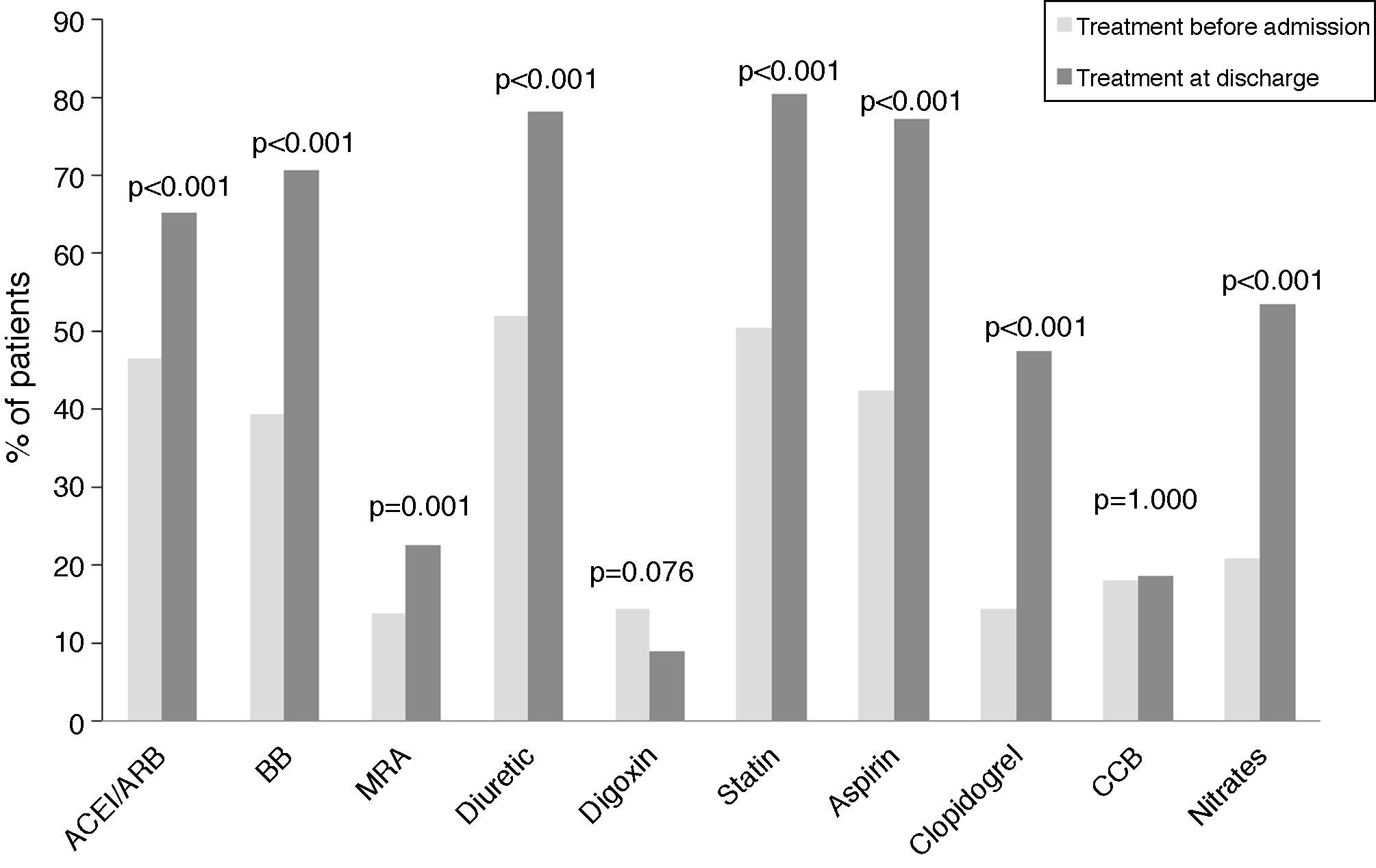

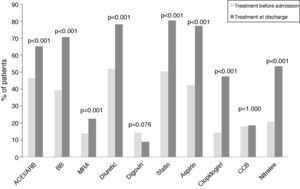

Comparing admission with discharge, we observed a significant drop in body weight (median −3kg [p25–p75: −6–0]; p<0.001), systolic blood pressure (mean −17.1mmHg; SD 29.7; p<0.001), heart rate (mean −18.7 bpm; SD 32.4; p<0.001) and BNP (median −203.5 pg/dl [p25–p75: −850.5–74.9]; p<0.001). There was no improvement in creatinine clearance, serum sodium and potassium, or serum hemoglobin. The rate of prescription of all cardiovascular drugs increased from admission to discharge, apart from digoxin and calcium channel blockers (Figure 1).

Oral medication on admission and at discharge for acute heart failure patients. McNemar test for related samples. ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; BB: beta-adrenergic receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

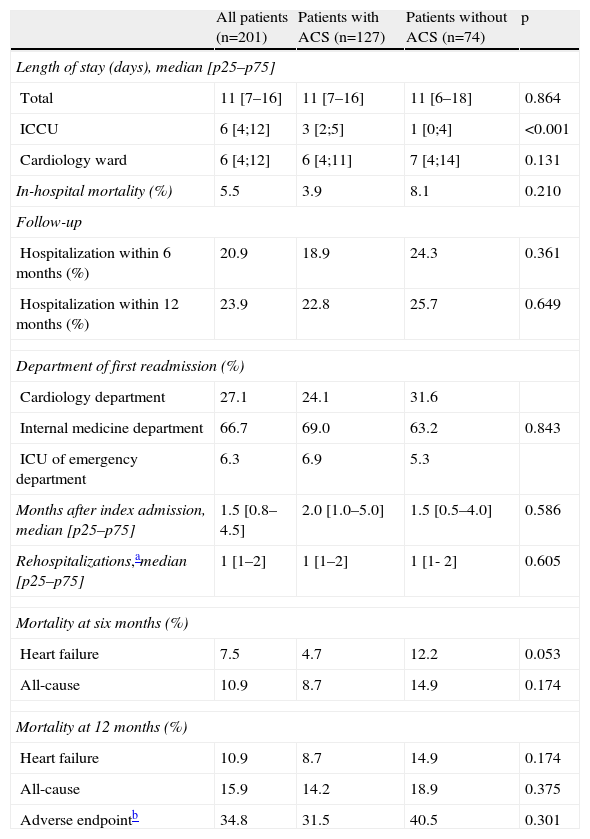

Total LOS was similar in the two groups (median 11 days). In-hospital mortality was 5.5% and was not significantly different between the two groups. The rate of rehospitalization for HF was 20.9% and 23.9% at six and 12 months, respectively. Most readmissions occurred within six weeks after the index event. All-cause mortality was 10.9% and 15.9% at six and 12 months, respectively. The variables independently associated with a longer LOS were history of HF hospitalization in the previous year (p=0.040), BNP >500 pg/ml (p<0.001) on admission and ICCU admission (p=0.002) (Table 1S in Supplementary Material).

The most important variables predictive of the combined endpoint of rehospitalization or death during follow-up were history of HF hospitalization in the previous year (hazard ratio [HR] 3.177 [1.405–7.185]), serum sodium<135 mmol/l on admission (HR 1.995 [1.032–3.856]) and AF (HR 1.791 [1.021–3.142]). Reduced LVEF (HR 0.518 [0.268–0.998]) was associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization or death (Table 2S in Supplementary Material).

DiscussionHospitalizations due to AHF are associated with high mortality and readmission rates, and represent about 70% of all costs associated with HF.10,11 They typically occur in internal medicine or cardiology departments and thus most studies include a mixed population from both provenances.

Clinical information provided by hospital-based studies is crucial to our understanding of the contemporary clinical characteristics of AHF, including key prognostic factors and details regarding clinical presentation and medical therapy. We therefore conducted a hospital-based observational retrospective study in order to identify the particular characteristics of AHF patients admitted exclusively to a cardiology department.

Demographics, underlying diseases, type of onset, precipitating factors and clinical presentation of acute heart failureIn our study, the mean age and gender distribution of patients were similar to those of previous AHF registries in Europe and elsewhere7,12 and in the USA.13 However, our patients were younger and more often male than those included in an earlier Portuguese study performed in internal medicine wards.9 Unlike in many previous reports, the majority of our patients had reduced LV function, which was perhaps a consequence of the high prevalence of ACS in our population. Interestingly, a recent Italian study14 also showed that patients admitted to cardiology departments were younger, more often male and more likely to have reduced LVEF than patients in internal medicine wards, which is in agreement with our findings but not with the aforementioned Portuguese study.9

Cardiovascular disease was common among our patients, most frequently CHD and hypertension, as observed in previous international surveys.7,12,13 Conventional cardiovascular risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes and dyslipidemia, were also very frequent. The prevalence of noncardiovascular comorbidities was similar to that observed in previous surveys 12,13. Chronic pulmonary diseases, anemia and kidney disease were common, with mean creatinine clearance compatible with grade 3 renal failure. This was similar to that observed in ADHERE,13 highlighting the importance of heart-kidney interaction in AHF.

Most patients had new-onset HF, particularly those with an ACS as precipitating factor. The prevalence of new-onset AHF was much higher than in EHFSII12 and ALARM-HF.7,13

ACS was the precipitating factor in nearly two-thirds of patients. This was almost twice the figure observed in reports7,12 that included patients of mixed provenance (from internal medicine and cardiology departments). Arrhythmias were the second most frequent precipitating factor and were more common in the non-ACS group. They were mostly of supraventricular origin, which is in line with previous reports of the high frequency of AF among AHF patients.

As in EHFSII12 and ALARM-HF,7 two of the most common clinical presentations of AHF in our population were CDHF and pulmonary edema.

Diagnostic investigations and treatmentECG, BNP measurement and echocardiographic examination were performed in nearly all patients on admission or within the first days of hospitalization, showing good adherence to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) HF guidelines.3 The high prevalence of ACS explains why coronary angiography was performed in more than two-thirds of our patients and why a considerably higher percentage of them were admitted to the ICCU, compared to EHFSII.12

As previously reported by others,7,12,13 ventilatory support and intravenous diuretic therapy played a central role in acute management. Non-invasive ventilation was used in the majority of patients. The frequency of administration of intravenous nitrates was similar to that in previous surveys,7,12,13 while the use of inotropes was nearly half. Approximately one-third of the patients presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. This was considerably more frequent than in ADHERE13 and EHFSII.12

The observed decrease in body weight, heart rate and BNP at discharge reflected clinical improvement with therapy. Interestingly, blood pressure fell, but no improvement in serum creatinine value was observed, which demonstrates the limitations of current therapeutic options regarding renal function.

The prescription of drugs recommended for HF, CHD and hypertension increased significantly from admission to discharge. However, the proportion of patients taking angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) was lower than in EHFSII12; a possible explanation for this may be the proportion of our patients (26.8%) with HF and preserved LVEF, for which these drugs are not formally indicated. By contrast, the levels of prescription of beta-blockers, statins, aspirin, clopidogrel and nitrates at discharge exceeded that of EHFSII,12 possibly because ACS was more frequent in our study than in that survey and these drugs are recommended for secondary prophylaxis of ACS.

Length of stay, outcomes and follow-up of acute heart failure patients (Table 4)The overall LOS was 11 days, two days longer than in EHFSII12 and ALARM-HF7 and almost three times that reported in ADHERE.13 The median ICCU stay was six days, twice that reported in EHFSII12 and ALARM-HF.7 However, in our case, in-hospital mortality was 5.5%, which was lower than in EHFSII12 (6.6%) and ALARM-HF7 (12%). The large-scale US surveys ADHERE13 and OPTIMIZE-HF15 reported in-hospital mortality of nearly 4%, which is even lower than ours. Nonetheless, this low in-hospital mortality, which may in part have been a consequence of the very short LOS, was counterbalanced by higher readmission rate and long-term mortality (for instance, OPTIMIZE-HF15 showed 90-day rehospitalization rates and mortality of 30% and 35%, respectively). It is possible that longer hospital stay could enable better patient stabilization, reducing long-term morbidity and mortality.

Length of stay, outcomes and follow-up.

| All patients (n=201) | Patients with ACS (n=127) | Patients without ACS (n=74) | p | |

| Length of stay (days), median [p25–p75] | ||||

| Total | 11 [7–16] | 11 [7–16] | 11 [6–18] | 0.864 |

| ICCU | 6 [4;12] | 3 [2;5] | 1 [0;4] | <0.001 |

| Cardiology ward | 6 [4;12] | 6 [4;11] | 7 [4;14] | 0.131 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 5.5 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 0.210 |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Hospitalization within 6 months (%) | 20.9 | 18.9 | 24.3 | 0.361 |

| Hospitalization within 12 months (%) | 23.9 | 22.8 | 25.7 | 0.649 |

| Department of first readmission (%) | ||||

| Cardiology department | 27.1 | 24.1 | 31.6 | |

| Internal medicine department | 66.7 | 69.0 | 63.2 | 0.843 |

| ICU of emergency department | 6.3 | 6.9 | 5.3 | |

| Months after index admission, median [p25–p75] | 1.5 [0.8–4.5] | 2.0 [1.0–5.0] | 1.5 [0.5–4.0] | 0.586 |

| Rehospitalizations,amedian [p25–p75] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1- 2] | 0.605 |

| Mortality at six months (%) | ||||

| Heart failure | 7.5 | 4.7 | 12.2 | 0.053 |

| All-cause | 10.9 | 8.7 | 14.9 | 0.174 |

| Mortality at 12 months (%) | ||||

| Heart failure | 10.9 | 8.7 | 14.9 | 0.174 |

| All-cause | 15.9 | 14.2 | 18.9 | 0.375 |

| Adverse endpointb | 34.8 | 31.5 | 40.5 | 0.301 |

Our results reinforce the notion that AHF hospitalizations are associated with poor prognosis, with more than one-third of patients dying or being rehospitalized over the subsequent year.

Our patients with new-onset AHF had a more severe clinical presentation, which is consistent with ALARM-HF.7 However, in the long run patients with CDHF had a higher risk of rehospitalization or death.

The probability of being rehospitalized was highest during the first weeks after discharge from the index event, which attests the need of an early medical appointment after discharge, preferably in the setting of a particular HF management program.3

Predictive factors of longer hospitalization and adverse outcomeThe predictive factors for rehospitalization after an AHF event are largely unexplored in the literature.16 In our study a baseline BNP value higher than 500 pg/ml was the most important factor associated with longer LOS, followed by admission to the ICCU, both indicating a more severe initial clinical picture. History of HF hospitalizations in the previous year, a recognized marker of bad prognosis,3 was also associated with longer hospital stay and with a threefold increase in the risk of dying or being rehospitalized during the year after discharge. AF also showed a significant association with increased risk of rehospitalization or death, which is in keeping with literature on CHF.3,17–21

Other variable also independently associated with a poor long-term outcome was serum sodium <135mmol/l on admission, while reduced LVEF was associated with better prognosis. Together they can help to select high-risk patients for inclusion in specific HF clinic. This is important, since these management programs can reduce rehospitalizations and mortality, are cost-effective and in the ESC guidelines have class I recommendation, level of evidence A, for recently hospitalized HF patients.3 However, in many countries, due to financial constraints and insufficient manpower, it is not possible to admit all hospitalized HF patients to an HF management program. Thus, identifying predictors of increased vulnerability can help to select patients most in need of these programs.

Patients with vs. without acute coronary syndrome as the precipitating factorPatients with an ACS typically presented left atrial dilatation, preserved left ventricular dimensions and reduced LVEF on admission. Left atrial dilatation was possibly a consequence of history of hypertension observed in more than 70% of patients. On the contrary, in the early days of new-onset AHF due to an ACS, the left ventricle would not have had sufficient time to undergo eccentric remodeling.

Patients with ACS had more frequent and longer ICCU admissions and were more often treated with non-invasive ventilation and intra-aortic balloon pump than those without ACS. This suggests they have a worse initial clinical course. Nonetheless, there was no difference between groups in total hospital LOS, readmission rate, in-hospital mortality or mortality at six or 12 months.

Study limitationsAn inherent limitation of this study derives from its retrospective nature. An additional drawback is the possibility that death or rehospitalization occurring out of our institution during follow-up were not reported. This could partly explain the observed low long-term rehospitalization and death rates. However, the consistency in the referral of patients indicates that this was probably not a major problem, and moreover cannot explain the low rates of in-hospital mortality also found in our study.

ConclusionPatients admitted to our cardiology department with AHF more typically presented new-onset AHF, in the context of an ACS, causing deterioration in LV systolic function. They had longer LOS but lower 12-month readmission rate and mortality than reported in US and European studies. Independent predictors of rehospitalization or death were HF hospitalization during the previous year, serum sodium <135 mmol/l on admission and AF. Reduced LVEF was associated with a decreased risk of rehospitalization or death.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor;

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor;