Coronary intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is increasingly important in catheterization laboratories due to its positive prognostic impact. This study aims to characterize the use of IVUS in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in Portugal.

MethodsA retrospective observational study was performed based on the Portuguese Registry on Interventional Cardiology of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology. The clinical and angiographic profiles of patients who underwent PCI between 2002 and 2016, the percentage of IVUS use, and the coronary arteries assessed were characterized.

ResultsA total of 118706 PCIs were included, in which IVUS was used in 2266 (1.9%). Over time, use of IVUS changed from none in 2002 to generally increasing use from 2003 (0.1%) to 2016 (2.4%). The age of patients in whom coronary IVUS was used was similar to that of patients in whom IVUS was not used, but in the former group there were fewer male patients, and a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes), previous myocardial infarction, previous PCI, multivessel coronary disease, C-type or bifurcated coronary lesions, and in-stent restenosis. IVUS was used in 54.8% of elective PCIs and in 19.15% of PCIs of the left main coronary artery.

ConclusionCoronary IVUS has been increasingly used in Portugal since 2003. It is used preferentially in elective PCIs, and in patients with higher cardiovascular risk, with more complex coronary lesions and lesions of the left main coronary artery.

A ecografia intravascular coronária tem ganho importância nos laboratórios de hemodinâmica pela evidência de impacto prognóstico positivo para os doentes. Este trabalho tem como objetivo caraterizar a utilização de ecografia intravascular em intervenções coronárias percutâneas em Portugal.

MétodosEstudo observacional retrospetivo com base no Registo Nacional de Cardiologia de Intervenção da Sociedade Portuguesa de Cardiologia. De 2002 a 2016 caraterizou-se o perfil clínico e angiográficos dos doentes submetidos a intervenção coronária percutânea, a percentagem de utilização de ecografia intravascular e as artérias coronárias avaliadas.

ResultadosForam incluídas 118 706 intervenções coronárias percutâneas, com utilização de ecografia intravascular em 2266 (19%). A evolução temporal caraterizou-se por ausência em 2002 e uma utilização maioritariamente crescente de 2003 (0.1%) a 2016 (2.4%). O grupo de doentes com utilização de ecografia intravascular coronária tinham idade semelhante ao grupo de doentes sem utilização de ecografia intravascular coronária, com uma menor prevalência de doentes do sexo masculino e uma maior prevalência de fatores de risco cardiovasculares (hipertensão arterial, hipercolesterolemia, diabetes), enfarte agudo do miocárdio prévio, intervenção coronária percutânea prévia, doença coronária multivaso, lesões coronárias do tipo C ou em bifurcação e reestenose intra-stent. A ecografia intravascular foi utilizada em 54.8% em intervenções coronárias percutâneas eletivas e em 19.15% das intervenções coronárias percutâneas do tronco comum.

ConclusãoA ecografia intravascular coronária teve uma utilização crescente em Portugal desde 2003, ocorre preferencialmente em intervenções coronárias percutâneas eletivas, de doentes com maior risco cardiovascular, com lesões coronárias mais complexas e lesões do tronco comum.

Coronary intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) has been used worldwide in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures for over 20 years.1 The technique provides cross-sectional images of the coronary arteries at a resolution of 100-150μm.2 When used in PCI, it complements information from fluoroscopic coronary angiography to determine the degree of luminal stenosis, identify and characterize the morphology of atherosclerotic plaque, optimize the choice of stent diameter and length, confirm correct apposition of stent struts after implantation, assess possible complications following angioplasty, and help elucidate the mechanisms behind stent restenosis.1

IVUS is a safe technique, with a complication rate of less than 1%.3 Its limitations are that it can only safely be used in coronary arteries with a luminal diameter of more than 1.5mm, due to the risk of occlusion by the IVUS device in smaller caliber arteries, and that its resolution is lower than other coronary imaging modalities such as optical coherence tomography (OCT).2 The latter uses infrared radiation instead of ultrasound to provide a resolution 10 times better (10−20μm) than with IVUS, but with less penetration (1-2mm vs. 4-8mm).4

The use of IVUS during PCI can influence the revascularization strategy adopted.5,6 Assessment by IVUS before stent implantation helps with the selection of stents and balloons of an appropriate diameter and length, with the result that larger diameter devices tend to be used when assessed by IVUS than when the technique is not used.5 Post-implantation, IVUS can be used to assess apposition of the stent to the vessel wall, which in practice more often leads to use of balloon post-dilatation.5,6 These modifications of the revascularization procedure have been associated with greater minimum lumen diameter post-PCI and a lower incidence of stent thrombosis and restenosis.5,6

Various studies, including observational studies, randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses, have compared implantation of drug-eluting stents (DES) guided by fluoroscopic coronary angiography versus implantation guided by IVUS, and have concluded that greater benefit is derived from the latter, including reduced incidence of stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and mortality.7–13

Besides the demonstrated clinical benefits, there is also evidence that PCI with IVUS-guided DES implantation is cost-effective, particularly in patients with conditions that increase cardiovascular risk, including diabetes, chronic kidney disease and acute coronary syndrome.12,14

On the basis of the available evidence, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)’s guidelines on myocardial revascularization, updated in 2018, state that the use of IVUS should be considered to assess the severity of unprotected left main lesions (class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B), to optimize stent implantation in selected patients (class IIa, level B), and to detect stent-related mechanical problems that could lead to restenosis (class IIa, level C).15

In Japan, IVUS is used in over 80% of PCI procedures.16 In Portugal, the technique is of growing importance and is increasingly used in catheterization laboratories, but the authors are unaware of the actual percentage of its use. This study aims to characterize the use of IVUS in PCI in Portugal over a 15-year period (2002-2016), in terms of percentage of procedures in which it was used, the clinical and angiographic profiles of patients, and the coronary arteries assessed.

MethodsStudy populationA retrospective observational study was performed based on the Portuguese Registry on Interventional Cardiology (PRIC), a prospective continuous voluntary registry of 23 Portuguese interventional cardiology centers under the aegis of the Portuguese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology. It complies with the Cardiology Audit and Registration Data Standards (CARDS), the European data standards for clinical cardiology practice defined by the ESC.17

Study groupsPCI procedures recorded in the PRIC over a 15-year period between its creation in 2002 and 2016 were analyzed. Procedures for which data were not available on the use or otherwise of IVUS were excluded, and the remainder constituted the study sample. PCI procedures were divided into two groups: with and without the use of IVUS. The percentage of IVUS use and the changes in this percentage over time, from 2002 to 2016, were calculated. The different clinical contexts in which PCI was performed were determined, and the percentage of procedures with IVUS use in each context was calculated. The clinical and angiographic profiles of each patient group were characterized and these profiles were compared between the two groups. The coronary arteries most often assessed by IVUS were also identified, and the percentage of procedures in which each artery was assessed was calculated.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables as count and percentage.

Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t test and the chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

The statistical analysis was carried out using STATA version 14 (College Station, Texas, USA). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

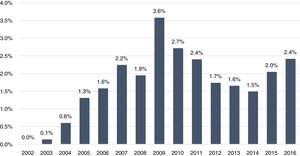

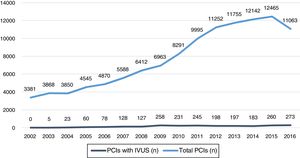

ResultsBetween 2002 and 2016, a total of 131109 PCI procedures were performed in Portugal, for which information on IVUS use was available in 118706 (90.5%), and these constituted the study sample. Of this total, IVUS was used in 2266 (1.9%) procedures and was not used in 116440 (98.1%). Over time, use of IVUS changed from none in 2002 to generally increasing use from 2003 (0.1%) to 2009 (3.6%), falling between 2009 and 2014 (1.5%), and rising again to 2016 (2.4%) (Figure 1).

The years with the greatest use of IVUS in PCI were in relative terms 2009 with 3.6%, and in absolute terms 2016 with 273 (Figure 2).

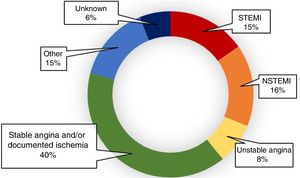

IVUS was used in the setting of stable angina and/or documented myocardial ischemia in 40% of cases, in non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 16%, in emergency primary PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 15.2%, in unstable angina in 8%, and in 14.8% of procedures for various situations classified as ‘Other’ in the PRIC, including heart failure, cardiomyopathy, valve disease, and arrhythmias (Figure 3).

Defining PCIs in the setting of stable angina and/or documented myocardial ischemia and PCIs classified as ‘Other’ as elective procedures, these accounted for 54.8% of cases in which IVUS was used.

Comparing the clinical profiles of patients undergoing PCI, the ages of the two groups were similar (63.9 vs. 64.8 years, p>0.5), but in the group in which IVUS was used there were fewer male patients (72.2% vs. 74.2%, p=0.028) and a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension [74% vs. 65%, p<0.001], hypercholesterolemia [66.5% vs. 54%, p<0.001] and diabetes [32.6% vs. 28.3%, p<0.001]), previous myocardial infarction (29.9% vs. 20.1%, p<0.001), and previous PCI (40.7% vs. 23.8%, p<0.001) (Table 1).

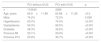

Clinical characteristics of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with and without the use of coronary intravascular ultrasound.

| PCI without IVUS | PCI with IVUS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 116440 | 2266 | |

| Age, years | 64.8±11.86 | 63.88±11.28 | >0.5 |

| Male | 74.2% | 72.2% | 0.028 |

| Hypertension | 65.0% | 74.0% | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 54.0% | 66.5% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 28.3% | 32.6% | <0.001 |

| Previous MI | 20.1% | 29.9% | <0.001 |

| Previous PCI | 23.8% | 40.7% | <0.001 |

IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

On angiography, patients undergoing PCI with use of IVUS were more likely to have multivessel coronary disease (58.6% vs. 50.9%, p<0.001), C-type lesions according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association classification18 (43.5% vs. 35.2%, p<0.001), bifurcated coronary lesions (13.3% vs. 8.2%, p<0.001), and in-stent restenosis (11.2% vs. 4.9%, p<0.001) (Table 2).

Angiographic characteristics of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with and without the use of coronary intravascular ultrasound.

| PCI without IVUS | PCI with IVUS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 116440 | 2266 | |

| Multivessel disease | 50.9% | 58.6% | <0.001 |

| C-type lesions | 35.2% | 43.5% | <0.001 |

| Bifurcated lesions | 8.2% | 13.3% | <0.001 |

| In-stent restenosis | 4.9% | 11.2% | <0.001 |

IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

IVUS was used in 1171 (2.55%) of PCIs of the left anterior descending coronary artery and in 383 (19.15%) of PCIs of the left main coronary artery (Table 3).

Percentages of use of intravascular ultrasound in percutaneous coronary intervention of different vessels.

| Vessel | PCI without IVUS | PCI with IVUS | Use of IVUS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left main | 2000 | 383 | 19.15% |

| Left anterior descending | 45999 | 1171 | 2.55% |

| Circumflex | 29237 | 537 | 1.84% |

| Right coronary | 38592 | 632 | 1.64% |

| Bypass graft | 1270 | 11 | 0.87% |

IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Of a total of 5043 PCIs treating in-stent restenosis, IVUS was used in 237 (4.7%).

DiscussionThe fact that IVUS was used in only 1.9% of PCI procedures performed in Portugal over the 15-year period 2002-2016 demonstrates the low penetration of this intracoronary imaging technique in the country.

One reason for this low usage could be the perception among operators that IVUS confers little benefit and that fluoroscopic coronary angiography is sufficient to assess coronary lesions. Nevertheless, various studies have shown that assessment of degree of stenosis and vessel diameter by angiography can be unreliable, subjective and only weakly correlated with the degree of myocardial ischemia.19,20 On the other hand, the benefits of IVUS-guided DES implantation have repeatedly been demonstrated, including reduced incidence of stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, MACE and mortality. Among the various meta-analyses published on this subject, that of Jang et al. in 2014,10 which included three randomized trials and 12 observational studies with a total of 24849 patients, concluded that IVUS-guided PCI was associated with a reduction in relative risk for all-cause mortality of 36% (2.3% vs. 3.3%, p<0.001), while in Elgendy et al. (2016),11 which included seven randomized trials with a total of 3192 patients, IVUS-guided PCI was associated with a 40% reduction in relative risk of MACE at 15 months (6.5% vs. 10.3%, p<0.001).

Another possible reason for the low rate of use of IVUS in this country may be the additional costs of the IVUS device and the lack of reimbursement by payers, particularly considering that the period under analysis (2002-2016) included a time of economic crisis in Portugal. However, the evidence shows that IVUS is in fact cost-effective and that costs are actually lower in selected patients when IVUS is used.12,14

The 2018 updated ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularization give IVUS class IIa recommendations for assessing the severity of unprotected left main lesions, for optimizing stent implantation in selected patients, and for detecting stent-related mechanical problems that could lead to restenosis.15 One would therefore expect a considerably higher rate of use than the 1.9% found in the present study.

Although in absolute terms the vessel most often assessed by IVUS was the left anterior descending coronary artery, in relative terms IVUS was used most frequently in PCI of the left main coronary artery. In view of the above specific ESC recommendations to use IVUS to assess the severity of unprotected left main lesions and to optimize stent implantation,15 we consider that the use of IVUS in only 19.5% of PCIs of the left main is clearly inadequate.

Similarly, given the recommendation in the ESC guidelines to use IVUS to detect possible mechanical problems leading to in-stent restenosis, in our opinion the rate of use in PCI to treat in-stent restenosis – 4.7% – is lower than desired.

In Portugal, decisions whether to use IVUS appears to be based on clinical variables such as the presence of cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia or diabetes) and a history of previous myocardial infarction or PCI, angiographic features such as complexity of coronary lesions (C-type or bifurcated), and the artery to be treated. IVUS thus appears to be reserved solely for a subset of patients at higher cardiovascular risk and to treat especially complex lesions and left main disease. Although these patients are indeed those most likely to benefit from the use of IVUS, we believe that its benefit would also be significant in patients at lower risk who are currently being denied access to this imaging technique.

Since the aim of this study is to characterize the use of IVUS, we should point out that this use may have been influenced by the development of more recent coronary imaging techniques, particularly OCT, which is not considered in the present analysis. However, although the advent of OCT may have been one of the factors responsible for the variations in IVUS use observed, especially the reduction seen between 2009 and 2014, we feel that this does not explain the overall low use of IVUS. In Spain, IVUS was used in 3672 PCI procedures (2.4%, curiously the same percentage as in Portugal), but this rate was higher than that of OCT, used in 2678 PCIs (1.7%),21 and it is therefore unlikely that in Portugal OCT would have been used sufficiently more frequently than IVUS to explain the latter’s low rate of use.

In light of the above results, particularly the proven positive prognostic impact of IVUS-guided PCI and its cost-effectiveness, the authors believe that the use of IVUS should be fostered in Portugal.

LimitationsThis study has the limitations that are inherent to any retrospective observational study based on a single registry. However, it should be noted that the PRIC complies with the CARDS criteria as defined by the ESC and includes a large number of centers (23 Portuguese interventional cardiology centers) and can thus be taken to represent the real situation in the country.

ConclusionsIVUS was used in 1.9% of PCI procedures over a 15-year period in Portugal, its rate of use growing overall and with the highest absolute number of procedures in the last year of the study, in 2016.

It is used preferentially in elective PCIs in patients with higher cardiovascular risk, with more complex coronary lesions and lesions of the left main coronary artery.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Guerreiro RA, Fernandes R, Teles RC, Silva PCd, Pereira H, Ferreira RC, et al. Quinze anos de ecografia intravascular coronária em intervenção coronária percutânea em Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:779–785.